The debate about the future of photo-books is not exactly new, but it's not dying down either. I'm not sure where this particular strand of the debate started, but in recent days Jörg posted a few provocative thoughts over at Conscientious, which are feeding into a "crowd-sourced" blog post that has been set up by Andy from Flak Photo and Miki from liveBooks. So here are my two cents...

Firstly, there is the question of technology. This debate should be placed into the larger context of the debate on the future of books, period. This has been stirring up the publishing world for some time now and there are enough questions in that sphere to fill a book (pun intended), let alone this post, so I won't delve too deeply here (for some interesting insights check out this Monocle podcast that was done following this year's Frankfurt book fair). From what I have gathered, the general sense is that the e-book revolution is primarily going to affect non-illustrated books. Firstly there is the question of size: looking at a photobook, or most illustrated books for that matter, requires a certain scale. I can't imagine many people stuffing a photo-book sized Kindle in their pocket before they walk out the door. In addition there is a stronger affective and emotional relationship with illustrated books than with paperbacks: people relate to the book as object and not just simply to its content.

Another interesting indicator of the resilience of the book form is the amount of websites that try to replicate a printed publication format online. One example, Purpose, a pretty good online photo-mag based in France, is made to resemble a print magazine as much as possible, down to an optional fold in the center of the the online mag to give it more of a print feel. I think that once the possibilities of the web are explored further on their own terms and less in terms of what we are used to in print, there will be a greater recognition of how web and print do different things well and therefore of how complementary they can be.

The second aspect of this technological issue is the advent of relatively low-cost digital printing combined with the emergence of web 2.0 and print-on-demand sites such as Blurb that make it possible for pretty much anyone to print their own photobook (just as digital cameras made it possible for pretty much anyone to call themselves a photographer). In an already very niche market where print runs tend to sit between 1,000 to 2,000 copies for most photo-books, does it make sense to have specialised photobook publishers like Aperture, Hatje Cantz or Nazraeli or should people just do-it-themselves and then distribute thanks to the joys of the internet?

Although RJ Shaughnessy's Your Golden Opportunity Is Comeing Very Soon was a great example of DIYism, I think that photo-book publishers are essential and will not be going anywhere. Firstly, a quick survey of the posts about Blurb and co demonstrates that they have some way to go to convince professionals in terms of quality. There is nowhere near enough control afforded to you through these sites to be able to get the same result as you do with a printing house where much more fine-tuning is possible. They provide a great affordable and decent quality alternative to lugging a portfolio around with you or to test a book project concept, but for most fine art photographers, this isn't enough. Perhaps their most important function is to provide amateur photographers or pro-sumers (whatever the hell they are) with a terrific, inexpensive way of experiencing other aspects of photographic practice, such as sequencing, editing, graphic design and production, which is welcome in an age where millions of images are being produced every second.

This brings me on to Jörg's recent post, which laments the lack of adventurousness and experimentation in photo-book publishing and questions why we don't see more 'curated' books i.e. "books where someone does in book form what you usually see in a gallery or museum." Unfortunately in my (admittedly limited) experience of publishing, consistently squeezed profit margins and schedules means that editors are increasingly being replaced by or transformed into managers who only have time for a very cursory glance at the content of the books themselves. But if anything, the print-on-demand sites are likely to make things worse by leading to books with off-the-shelf design templates and which are produced in a limited number of standard formats. Worst of all, 99% of the time, there is no editor involved in the process.

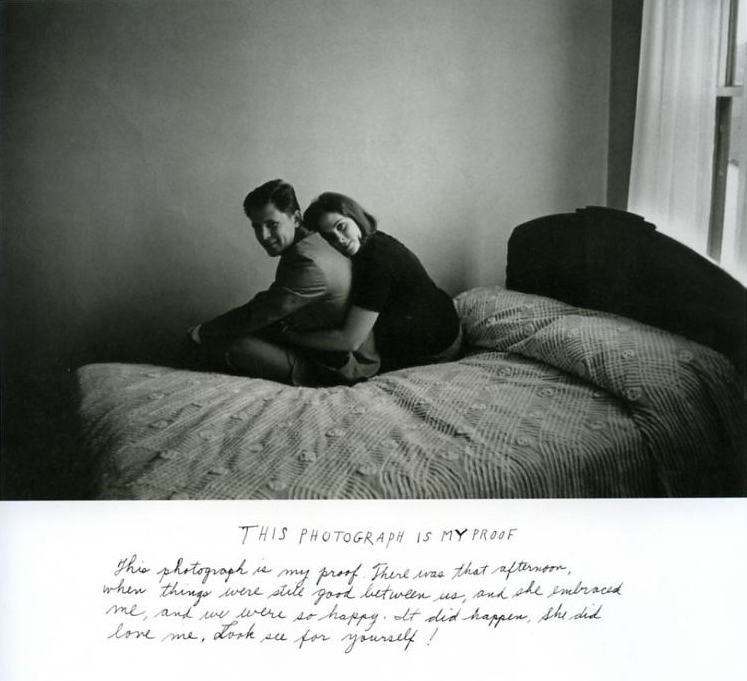

There is an ongoing debate in the literary world surrounding how much of a debt Raymond Carver owes to his editor, Gordon Lish, for his signature sparse, economical, yet powerfully evocative style. Editors with this much creative influence are hard to find today, but they are no less important than in the past. Editors of photo-books are just as crucially important, particularly when it comes to reducing a series down to its essence and trimming off all excess fat. In such a small niche as fine art photography, they also have a huge general influence on the photographic landscape. To take my default example of Japan, Japanese photography would look very different if Shoji Yamagishi had not been around.

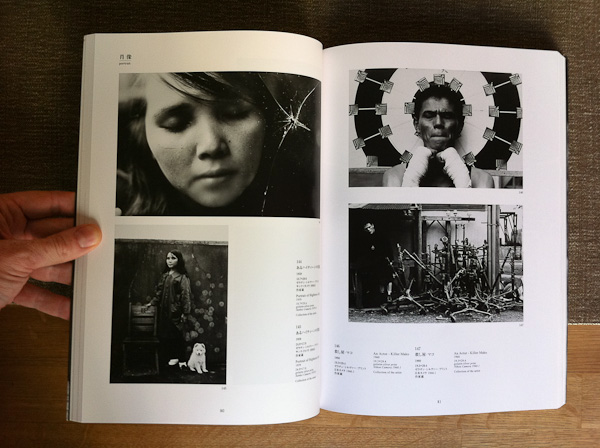

To go back to Jörg's point, it is true that most photo-books are monographs or exhibition catalogues, but this is only logical given that the sales of photo-books are so closely tied to exhibitions: there just would not be enough copies sold without them. In addition I think that these three forms (monograph, exhibition catalogue or collection catalogue) still offer a huge scope for experimentation. If anything, I think that the photo-book world may even be more experimental than the museum world at the moment. To illustrate my point here are a few examples that spring to mind.

Toluca Editions (that Mrs Deane posted about recently) have been around for a while on the Parisian photo scene, producing extremely high-end portfolios of work which are a collaboration between the artist, a writer and a designer. You could argue that these aren't strictly speaking books, but they are a great illustration of how far you can stretch the form. In a similar vein, but with a far more classic traditionalist feel, as part of my work with Studio Equis I have been collaborating with a Kyoto-based printing company, Benrido, that has combined nineteenth century colotype printing techniques with digital technology to produce a series of portfolios with truly exquisite results. Nazraeli are publishing a book next year in which Naoya Hatakeyama has collaborated with a French novelist, Sylvie Germain, who wrote a short story inspired from his series of underground images entitled Ciel Tombé. The book doesn't even exist yet, but this is an example of another way in which the photo-book form is being expanded beyond a group of images accompanied by descriptive text. Artists' books are another hugely rich field: on my last trip to Japan, Kikuji Kawada showed me a copy of the retrospective book he had produced (in an edition of 1) entirely with his own hands made up from several hundred digital prints painstakingly sequenced and hand bound into a mammoth encyclopaedic tome. To indulge in a bit of shameless self-promotion, I was able to get a study of postwar Japanese photography published by Flammarion in English and French at a time (2004) when virtually nothing had been published outside Japan on this period. I will stop there as this post is already far too long, but these examples are just the tip of the iceberg. You may need to go towards the fringes to find it, but experimentation in photo-books is alive and well.

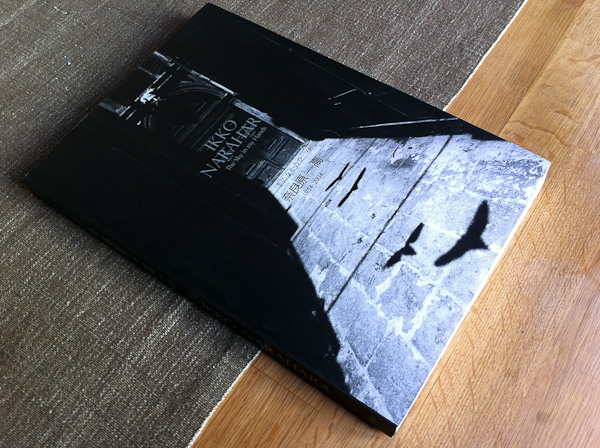

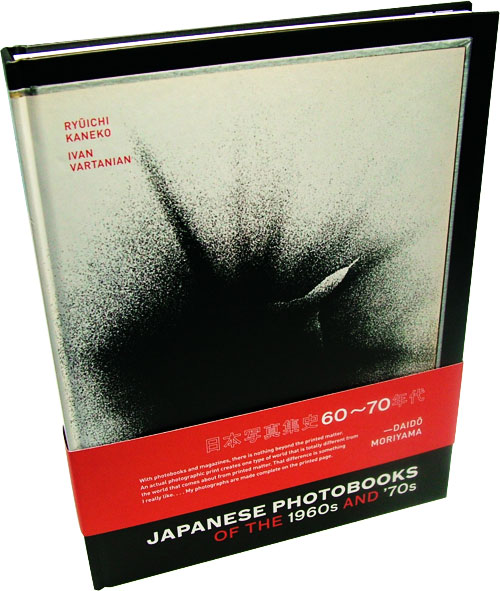

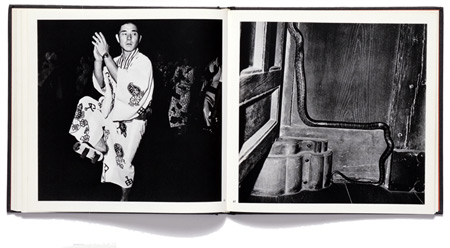

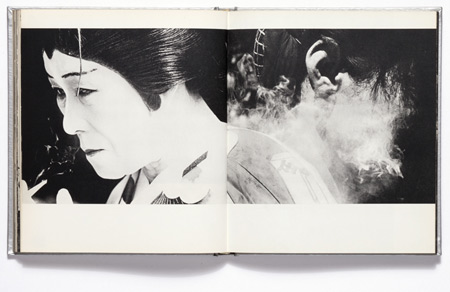

The recent books on books (Parr and Badger, Errata Editions' Books on Books series and the recent Japanese photobooks of the 1960s and '70s) provide evidence that the importance of photo-books within photography is increasingly being recognised. The future looks pretty exciting from where I'm sitting.

Update: