As the eyecurious faithful (and anyone who has been in Paris recently) will have noted, this has been a particularly action-packed month for photography in Paris. As I noted in a previous post, there was a bunch of different events going on at once and, as November draws to a close, I thought I would pull together a few brief impressions from the past month of photo-gluttony.

Paris Photo, the photo art fair, remains the major event on the Paris photo calendar. As with any art fair, it is not an experience for the faint-hearted or the sensitive-eyed. The fair squeezes several thousand photographs into a pretty restricted space underneath the Louvre, far more than 2 eyes and 1 brain can hope to absorb over a long weekend. Having started the week with three days of portfolio reviews at the first edition of FotoFest Paris (on which more later) it felt like a week of serious visual overindulgence.

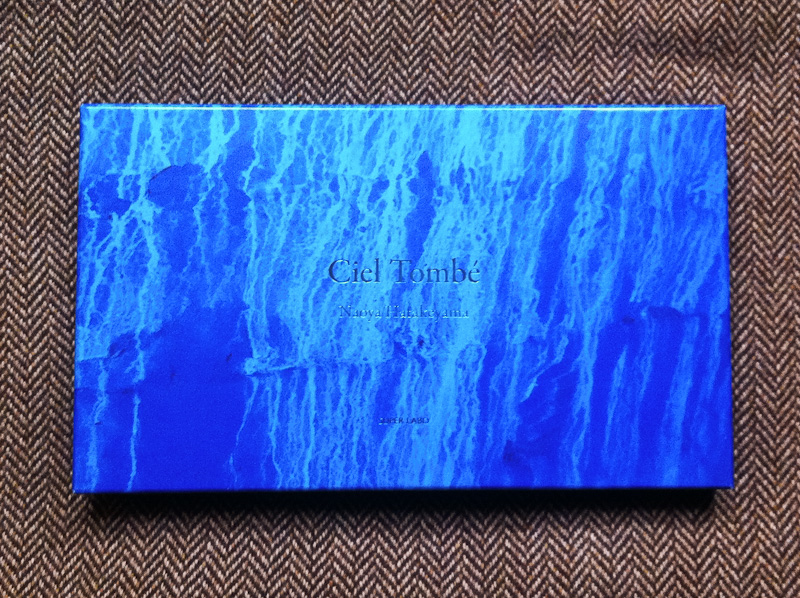

A quick scan of the round-ups of the fair around the web will reveal that there is no consensus whatsoever on the highlights of the year and that is in part because it is virtually impossible to see everything. My overall impression is that this was not a particularly adventurous year in terms of new work and the focus appeared to be on bringing big name vintage work. Hamburg's Robert Morat gallery bucked that trend with a great selection of work by Robert Voit, Peter Bialobrzeski and Jessica Backhaus. There are always a couple of artists that pop up on several booths and this year Michael Wolf's Tokyo subway and Street View images and Massimo Vitali's bleached-out beaches were the two that I kept running into. As always 'curated' booths were few and far between, which is understandable given the commercial nature of the fair. However there were a couple of exceptions: for his first Paris Photo, Paris's François Sage presented (and sold all of) 20 pieces from Naoya Hatakeyama's Maquettes/Light series combined with vintage night work from Kertész, Brassaï and others; while Serge Plantureux's booth was "transformed into a detective agency" built around an extraordinary collage of every building on a 1930s St Petersburg street which spanned the full length of his booth. And a favourite discovery from last year, Maurizio Anzeri, reappeared again with some more great pieces.

I suppose the natural measure of the success is sales and on this, once again, I heard wildly different assessments (Paris Photo gives it upbeat round-up here). However, for me the measure of the success of the event is its ability to bring together photographers, curators, dealers, publishers, bloggers and 40,000 other people from around the world in a single place, which, fortunately for me, happens to be where I live. On this count it feels to me that the fair continues to get more and more international each year and the best possible place to get photo projects in motion. My personal highlights included meeting the extraordinary photographer Mao Ishikawa from Okinawa and a champagne-fuelled meeting with Joakim Stromhölm (Christer Stromhölm's son) in the early hours of the morning.

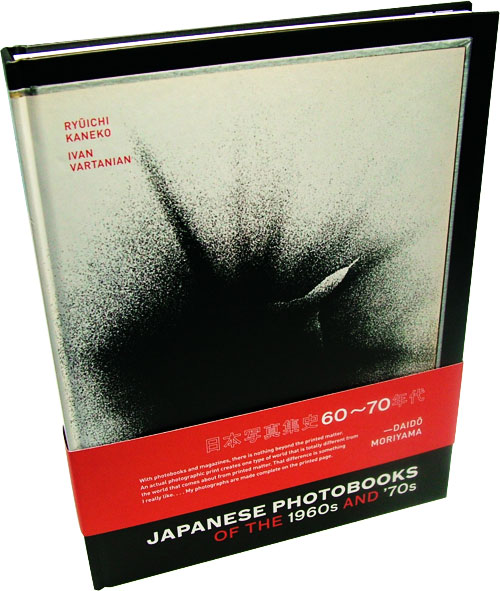

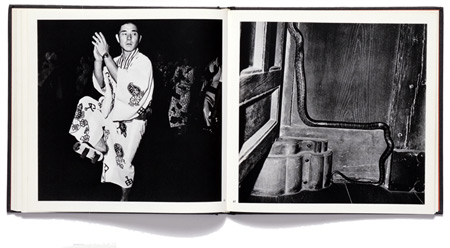

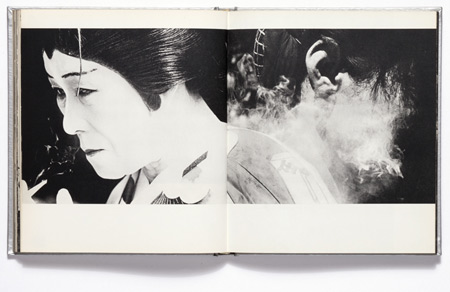

One particularly interesting development this year was the first (and hopefully not the last) edition of Off Print, a fair run in parallel to Paris Photo devoted entirely to independent photography publishing, an area that is currently seeing an explosion of activity. I was curious to see whether Off Print would be able to coexist alongside Paris Photo and pleasantly surprised to see that it more than held its own. I managed to swing by three times, always to a packed house where business seemed to be brisk. Interestingly while there was some overlap with the Paris Photo crowd, Off Print was clearly attracting a different demographic as well, a younger crowd that is perhaps more interested in the book as an object rather than just in photography itself. If evidence were needed that photobooks are alive and well, this was it.

After several failed attempts I finally managed to swing by Photo Off on Sunday afternoon to finish the week. Photo Off is essentially a more casual Paris Photo, with lower priced work by "young and emerging" photographers. From my couple of hours there I couldn't tell how successful the fair was, but it did seem a little bit strange to me that Photo Off and Off Print didn't combine forces, as I think three simultaneous event is probably a little too much to get through for collectors and as a result I expect that Photo Off didn't get the audience that it should have.

On the day after the close of Paris Photo as I was trying to make some sense of everything I had seen over the course of week (and to avoid looking at a single photograph) I received a package from the US. I had completely forgotten that a couple of weeks ago I decided to rescue a group of work prints by the photographer and blogger Blake Andrews that he was threatening to abandon. I thought this was a fitting end to a week where the commercial aspect of photography can feel a little overwhelming. Not only did I get a few dozen prints for my $9, but if you look closely at the image above you'll notice that I even got a stick of gum thrown in for good measure. I doubt that any collectors got that kind of special bonus thrown in with their purchases at Paris Photo.