Jon Rafman is a Canadian artist and filmmaker based in Montreal. He recently gave a talk about his work entitled “In Search of the Virtual Sublime” at the Gaité Lyrique, a new space devoted to digital culture in Paris. I met up with Jon in a café near the Jardin du Luxembourg to discuss Google Street View, street photography, the cyberflâneur and what the future looks like.

How did you start working in the digital space?

After I graduated I discovered a community of artists on the social bookmarking site del.icio.us. It really felt that an incredible artistic dialogue was taking place informally: a new vernacular was being formed online. There was so much energy to it. The dialogue was so exciting, mixing humour and irony, critique and celebration. Del.icio.us was the platform on which I really started working with the Internet. At this point Facebook and Tumblr have pretty much replaced it.

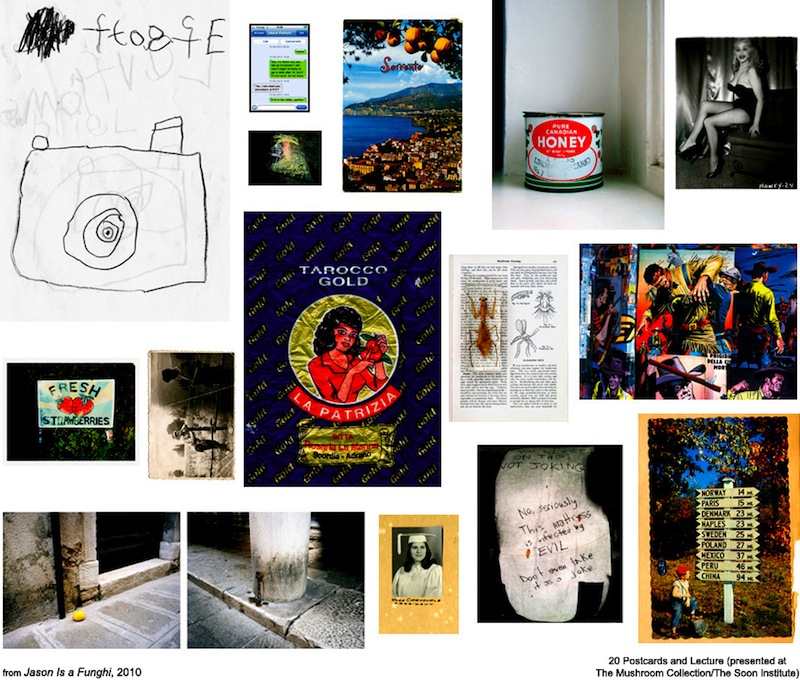

I had known about early net art but I was never attracted to its glitchy aesthetic. So when I discovered this community I felt like I had found what I had been searching for all through art school. Del.icio.us led me to various different collectives like Paintfx. That is the period when I started my Google Street View project.

The project started out as PDF books. And then I started to print out the images just like photographs. I experimented with the printing for a while and eventually decided to print the images as large format C-prints. In 2009 the art blog Art Fag City asked me to write an essay, and that was when the project really took off, but I already had a huge archive of material by that stage. The 9-eyes tumblr blog came directly out of that. I had already been working with Google Street View (GSV) for one or two years when I created 9-eyes.

What was your process to find the locations and images that you used?

At first it was just long, arduous surf sessions. I went to places I wanted to visit, mainly in America (GSV had not been launched in many countries at the time), but not in a systematic way. As the project grew, I learned certain tricks. For example the best place to go for images is to check where the Google cars are and to follow those. Otherwise, Google may have removed any ‘anomalies’, which often make the most interesting images.

Once the project went viral I started getting tons of submissions from people. Some of these I used directly and some would act as a departure point to search for images.

What were you looking for specifically?

I was working a bit like a street photographer: keeping an open mind and responding to my intuition. The process was really about editing down. The entire project is a process of subtraction: since everything has already been captured on GSV, it is about editing down until you find the core, essential moments. I think it could be considered as a major editing project.

Are there any online GSV communities or forums that you use to find images?

There is a forum for pretty much anything you can think of. There is a forum where people only collect images of prostitutes, some of which I used in 9-eyes. I don’t like fetishizing labour. I don’t want to play up the amount of time I spend finding these images. This can become a kind of artistic crutch. The greatest works of art for me can be a single gesture that took very little time at all.

Even though this project is inherently time consuming, I don’t want that to be its central focus. It could easily have become an endurance piece, a kind of artistic marathon. If I had an algorithm to find all these amazing images, I think I would be equally as happy.

Take Duchamp’s ready-mades: they changed art. If everything can be art, then what is art? I see that as the healthiest state for art to be in: questioning its very nature.

How conscious were you of specific street photographers’ styles when taking these images?

I was very aware of photographic history when working on this project. I really believe that photography was the medium of the twentieth century, because of the ambiguity surrounding the question of whether it was or was not art, due to photography’s mechanical nature. I saw GSV in some way as the ultimate conclusion of the medium of photography: the world being constantly photographed from every perspective all the time. As if photography had become an indifferent, neutral god observing the world.

The perception of reality associated with photography is very modern. In the past, representations in the form of images were always imbued with a certain magical quality. The photograph shows a world that is empty of that. It is just a reflection of the surface of things. In that way the photograph is the perfect embodiment of our perception of the modern world. More than specific photographic history, I was thinking of photography from a philosophical point of view.

Most of your work deals with digital media of some kind. Do you consider yourself to be a digital artist?

For a while the term “Internet-aware” was used in relation to artists working with the Internet. Nobody was happy with the term, or with “net artists” which felt too ghettoising. In the same way, many people do not feel comfortable with the term “new media artist”, because it implies a kind of fetishisation of new technology.

I would prefer to be recognised simply as an artist. Unless you are very specific to a medium, which I’m not, I don’t think it is necessary to add these labels. I’m fine with championing net art, but I don’t want to be wedded to it forever.

Take Elad Lassry for example. He is one of the most successful young photographers that I know, and in some way I think that is because he doesn’t position his work as photography but as art. I have a lot of respect for those ‘purists’ that are attached to the formal qualities of their medium, but I don’t want to be associated too closely with a particular medium as I’m interested in exploring many different approaches.

There are other artists, including Michael Wolf and Doug Rickard, who have worked with Google Street View. Do you see GSV as a territory where there is only room for one or do you see it as a vast territory that more and more artists are likely to explore?

GSV is in the zeitgeist and it is a vast territory to explore. In a way I’m surprised that there haven’t been more artists working with it. We all have different methods of working. For example, Michael Wolf photographs the screen to make his images, whereas I think that Doug Rickard removes all traces of Google from the images: the symbols, the Google copyright. My process is more akin to the ready-made.

You have also referred to the flâneur in relation to your work. How does this term that is generally associated with nineteenth century art in Paris relate to your practice?

I’m very interested in the notion of the flâneur. The lack of history in this new post-internet age is making it harder to have a sense of self. The Internet has already become so ubiquitous, that it is now a banal part of our reality.

In Internet years things are forgotten so quickly. The importance of history in building a sense of self is one of the main themes running through my work. Many of my projects focus on very marginal sub-cultures such as gaming (ed. Codes of Honor, for example). They feel the lack of a sense of self acutely because their culture can die out any day. The game is everything to them but from one the day to the next the culture of that game becomes obsolete.

The reason I tie in the flâneur is because I want to find the connection between the cyberflâneur and the flâneur of the Parisian arcades of the late nineteenth century. On one level the comparison is absurd, but on another level it is very apt. In the same way that Internet cultures die off, so did the arcades of Paris.

People talk about how the Internet age is so new, and the idea that technology has changed everything. I think it is very important to see that many of these things existed in different forms in the past. For instance, the information overload that is thought of as defining the Internet era dates back to early modern times and the emergence of the modern city.

The NYTimes recently published an article by Evgeny Morosovabout the death of the cyberflâneur. Morosov makes the point that in the age of social media, web surfing is essentially over, that the information we get from the Internet is essentially pre-digested. Do you agree with that view?

People often ask me what the future is going to look like… I’m not really sure why… maybe simply because I work with new technologies.

In the past we relied on dystopian and utopian views of the future. The future was thought of as fundamentally different from the present. Today, there is a sense that the future is going to be a lot more banal, that we are already living in the future (like with the phone that you are recording this conversation with), that the future is going to be more of the same… more apps and technologies that are designed to mediate and ‘improve’ our experience of reality. It is essentially a more Facebook-like future. This is very different from the early Internet, which was more like an exploration of a vast unknown territory.

Note: Jon Rafman's latest exhibition, MMXII BNPJ, opens at American Medium in New York on May 5.