Installation view, Natural Stories

My most recent trip to Japan in October happily coincided with Naoya Hatakeyama's first retrospective at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. Regular readers will know that I am a big fan of his work – and there is quite a lot of it – so I was curious to see how this exhibition, entitled Natural Stories, would be put together. The exhibition has now closed in Tokyo but opens at the Huis Marseille in Amsterdam today until the end of February 2012. To coincide with Natural Stories, Hatakeyama also released his latest book, Ciel Tombé, which I included on my best books of 2011 list, so I thought I would discuss them together here.

I will admit to being a little surprised at the selection of work in Natural Stories. Although there are ten different bodies of work in the exhibition, none of Hatakeyama's work on Tokyo (Underground, River, Maquettes/Light...) was included. However, in the curator's text on the exhibition she is quick to explain that this was a conscious decision given that Hatakeyama already had several solo exhibitions in Japan including a 2007 show at the Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura & Hayama which took the city as its theme. With that in mind the exhibition's focus on the natural landscape makes sense.

The title Natural Stories is an intriguing one. I think it works best in french (Histoires naturelles), which I believe is the language in which the title was originally given. In french 'histoire' can mean both history or a story. The title evokes Natural History, stories about nature, and perhaps even a history of nature itself. The essay by the French writer Philippe Forest in the exhibition catalogue explores these notions in detail so I won't dwell on them any further, but the title evokes the very different considerations that inform Hatakeyama's photographic approach to the landscape. His landscapes are never 'just' landscapes: they are always the reflection or the echo of something else. For instance, although it depicts the limestone mines, the series Lime Hills deals with the transformation of the natural landscape to feed the insatiable growth of the city of Tokyo.

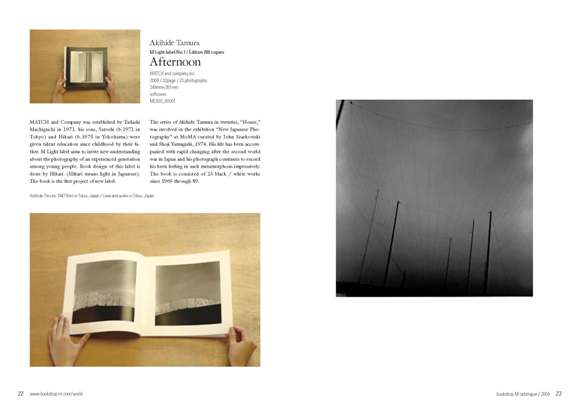

Ciel Tombé (Super Labo, 2011)

Although it is almost never directly present in this exhibition, the city is never very far away. In the series Ciel Tombé Hatakeyama explored the Parisian catacombs and their underground 'fallen skies' (ciel tombé). This series is the subject of Hatakeyama's latest book, Ciel Tombé (Super Labo, 2011). For this book Hatakeyama has deviated from the standard photobook formula and asked the French author Sylvie Germain to contribute a short story based on his photographs . I won't go into detail about this book as this post is already overly long, but I will say this: I first saw the work from Ciel Tombé a few years ago at a gallery in Tokyo. Several months later I had the opportunity to read Sylvie Germain's deliciously strange and unsettling text. I had not seen any of the images since that first viewing, but as I read through the story the images appeared in my mind as if I had only just seen them. For the moment the book only exists in a deluxe edition of 200 which includes a print, a book of Hatakeyama's photographs and another book containing Sylvie Germain's text in French, English and Japanese, but there is word of a second edition in the making.

Ciel Tombé (Super Labo, 2011)

Returning to Natural Stories, for me the final two rooms of the exhibition were the highlight. The first of these rooms (pictured at the top of this post) contained Hatakeyama's most recent work on his hometown of Rikuzentakata in Iwate prefecture, one of the many towns destroyed in the tsunami of 11 March 2011. Although very little time has passed, Hatakeyama decided to include a series of photographs in the exhibition that he took in the wake of the disaster. Many images have been produced of the aftermath of the tsunami, but most of these fail to connect beyond conveying the scale of the physical destruction. What stands out about Hatakeyama's images is how matter of fact they feel. He has photographed these landscapes with the same unflinching precision, intelligence and quietness tinged with nostalgia as any other landscape. His photographs strike me as the most natural possible response to the disaster, but they must have been incredibly difficult to make given the deeply personal and tragic nature of the subject. These images are presented on three adjacent walls in the space, while on the fourth a slideshow of images taken between 2008-2010 in his native region is presented in the guise of a framed photograph.

The final room contains the companion series Blast and A Bird. Both series have been exhibited and published in the past, but for this exhibition Hatakeyama also chose to present Blast as a stop-motion video projected on a huge wall in the space. These photographs have a potent mix of beauty and brutal force which is heightened even further when animated in this way. It is an overwhelming end to the exhibition and one which resonates long after you leave the space.

Installation view, Natural Stories