Since the earthquake of 11 March, Japan has slowly faded out of the international news, barring the occasional update on the nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi plant. However things remain critical in the northeast of the country and disrupted as far south as Tokyo as a result of the lingering problems at Fukushima and the associated disruptions to the power supply in the region. I had originally planned a 2-week trip to Japan, but in view of the disastrous events of last month and the very unclear portrayal of the situation in the international media, I decided to shorten my trip to 5 days. This is the first of a few posts from my recent visit, which will hopefully offer a slightly different view of Japan to the news coverage of recent weeks.

Since the earthquake of 11 March, Japan has slowly faded out of the international news, barring the occasional update on the nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi plant. However things remain critical in the northeast of the country and disrupted as far south as Tokyo as a result of the lingering problems at Fukushima and the associated disruptions to the power supply in the region. I had originally planned a 2-week trip to Japan, but in view of the disastrous events of last month and the very unclear portrayal of the situation in the international media, I decided to shorten my trip to 5 days. This is the first of a few posts from my recent visit, which will hopefully offer a slightly different view of Japan to the news coverage of recent weeks.

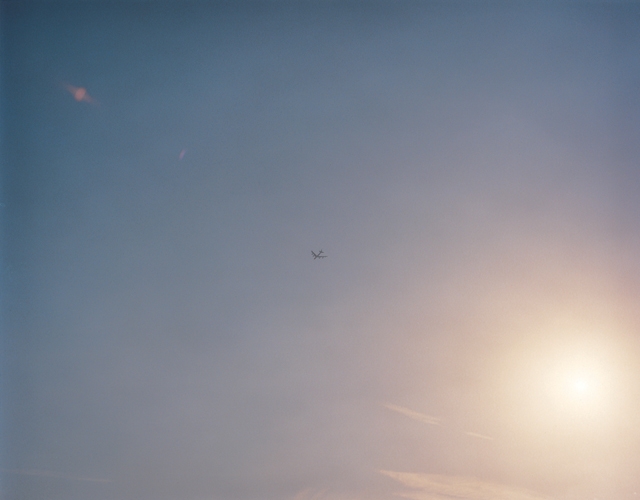

I started my trip by flying directly to Okinawa, approximately 1,000 miles to the south-west of Tokyo. From the moment you arrive it is clear that Okinawa is a far cry from Tokyo's urban super-futurism or the refined minimalism of Kyoto's temples. A chain of lush tropical islands, Okinawa's relationship with Japan is a historically complicated one, made even more so by the prolonged and powerful influence of the United States since World War II. Even today, American military bases occupy nearly 20% of land on the main island of Okinawa, while 85% of Okinawans oppose their presence.

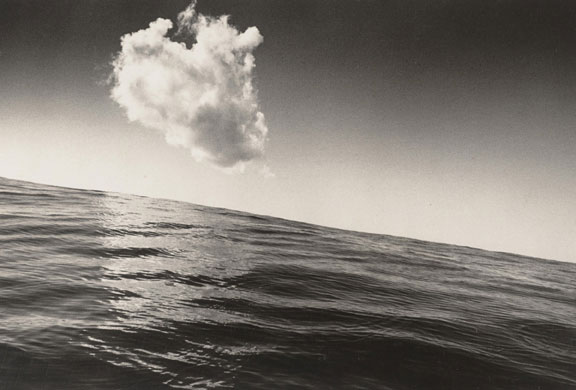

This combination of natural beauty and rich folklore with a pretty tense political context have made Okinawa a popular subject for Japanese photographers over the years. Shomei Tomatsu, Takuma Nakahira, Daido Moriyama, Araki... the list of mainlanders to have photographed there is long. Tomatsu, probably the best known photographer to have worked extensively in Okinawa, has made the island his home in recent years. More than any other mainlander's, his work goes beyond the surface of the island's beauty and mystery (I would highly recommend getting your hands on his 1972 book, Okinawa, Okinawa, Okinawa, although it is likely to set you back a pretty penny). And yet, even after shooting in Okinawa on and off for close to 40 years, Tomatsu is the first to point out that work by native Okinawans is not getting the recognition it deserves outside of the island.

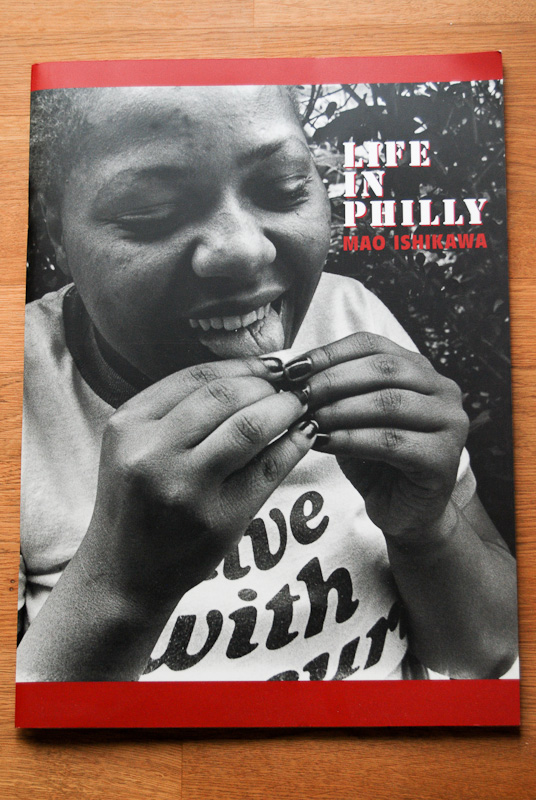

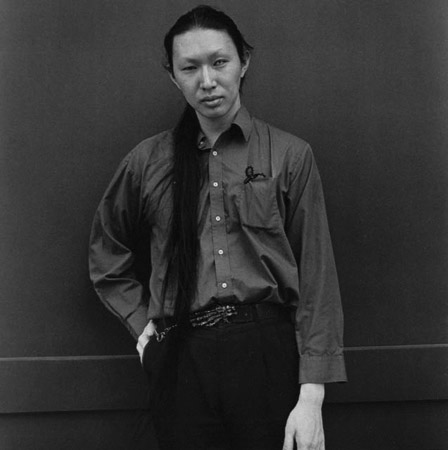

I came to Okinawa to visit Mao Ishikawa (regular readers might recognize her name from a few previous posts), a proud native Okinawan and a pint-sized force of nature. Before making this trip, I had just spent one hour with her at Paris Photo last November, which was more than enough to convince me that I needed to see more of her work.

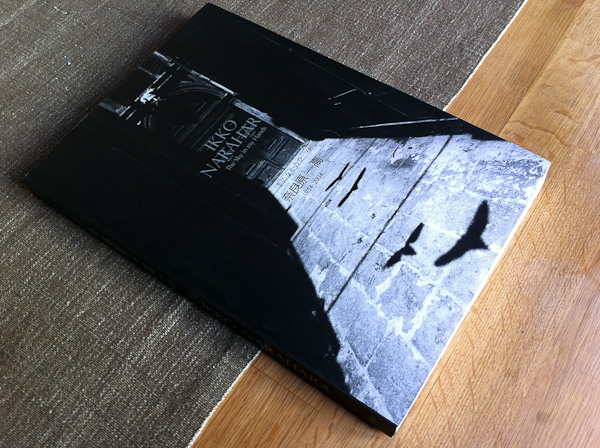

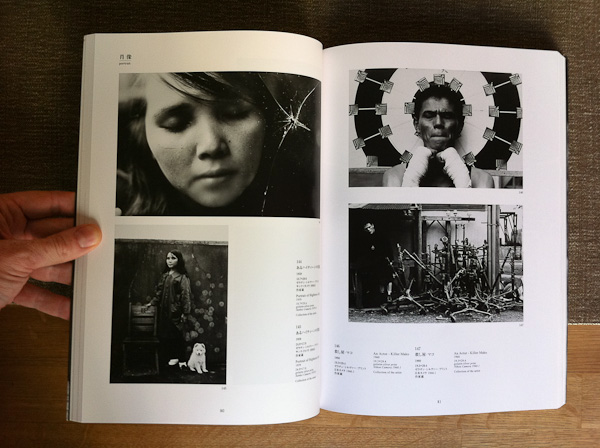

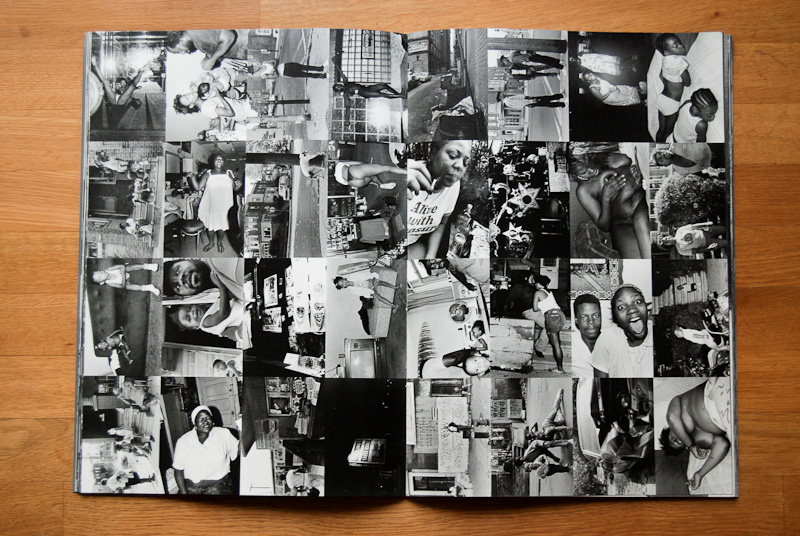

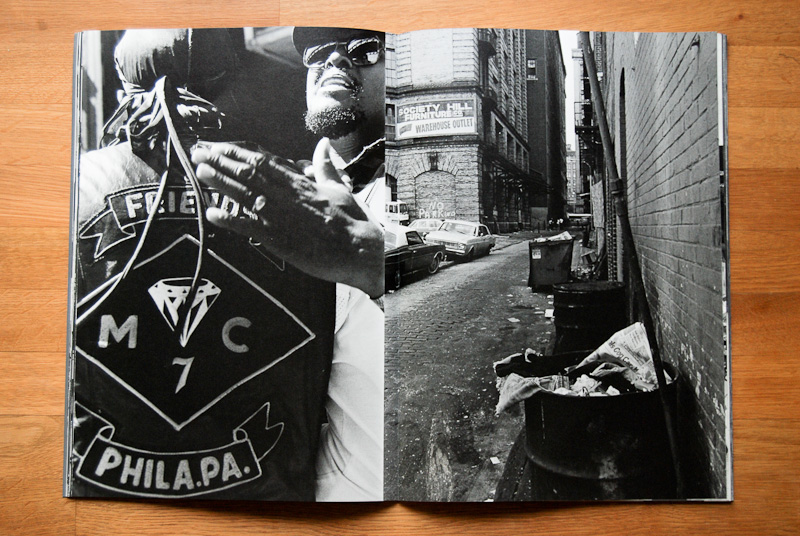

To say that Mao's story is extraordinary is a bit of an understatement. In the early 70s, after a few months at photography school in Tokyo (where she had picked out Tomatsu as her professor after seeing his pictures) she dropped out and headed back to her home town. Fascinated by the American military presence in Okinawa, Mao decided to become a hostess in a bar for African American soldiers (the US military actually enforced segregation on the bars that sprung up around the military bases) and to photograph her life there. The bar became her home for over 2 years and she photographed everything there with total freedom and openness… the other girls, the soldiers, the drinking, the smoking, the sex. While still in her early 20s, at a time when photography was a totally male-dominated world, she was one of the few women to get her pictures noticed, even managing to find a publisher for a book, which ended up causing quite a stir. During this time, one of the customers of the bar, a soldier named Myron Carr, became Mao's closest friend and after he returned to Philadelphia they remained in touch. In the 1980s she went to visit Carr and his twin brother, Byron, in their neighborhood in Philly and spent 2 months shooting there (recently published as Life in Philly, which I reviewed on the blog last year). She has successfully beaten cancer twice and is a fierce and longstanding critic of the continued US military presence in Okinawa. For her series Fences, Okinawa she walked around the perimeter of the fences surrounding the US military bases in Okinawa for an entire year, a project that her knees have yet to recover from.

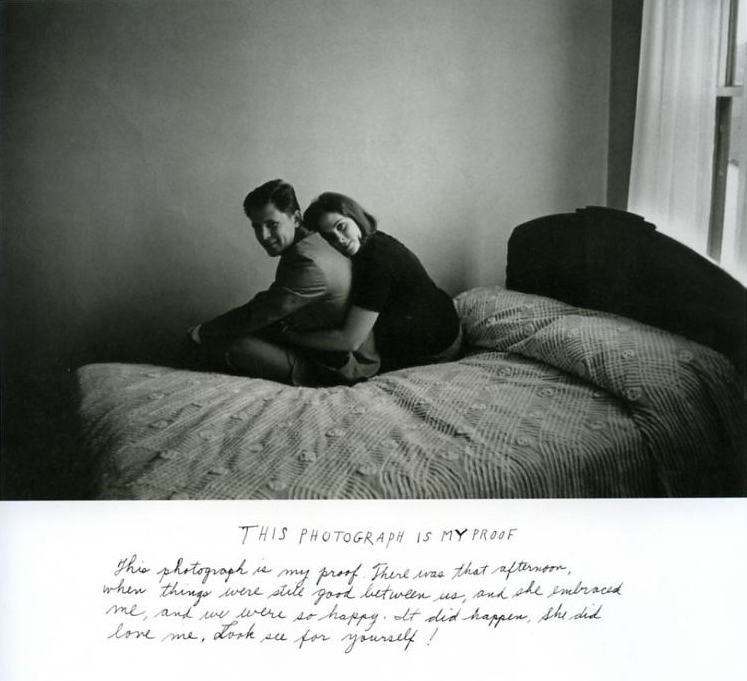

After almost 12 hours going through her archive (and barely scratching the surface), the thing that stood out most for me is that her images are always those of an insider, whether she is shooting a family theater company, a group of heavy-drinking dock workers, or life in one of Philadelphia's rougher areas. Documentary photographs can often be a collection of stolen moments, but it is clear that Mao's images involve a deep and genuine exchange. She isn't just observing the people that she photographs, she immerses herself in their world and makes it her own.

Mao's first solo exhibition in Europe, (from which I stole the title of this post) was organized last year in London by Naoko Uchima, a young Okinawan who recently relocated from London to her native island to promote its culture and photography. During the handful of hours I spent on the island Naoko also introduced me to the work of Yasuo Higa, an Okinawan photographer who passed away in 2000. Although I haven't yet had much time to properly explore his work, Higa's photographs focus on the disappearing rituals and folklore of Okinawa. His work is more lyrical than Ishikawa's and is imbued with a strong sense of spirituality. A Higa retrospective is on show at the Izu Photo Museum until 31 May 2011.

Spending 24 hours in Okinawa was never going to give me more than a glimpse into the life of this island, but a glimpse was more than enough to convince me that I need to go back.