I'm still in Japan stocking up on material for a few weeks worth of blogposts so things will remain slow at eyecurious for a few more days. In the meantime, check out the three-part Future of Photobooks Discussion that is being hosted on the Livebooks Resolve blog. I am moderating one of the 3 strands of discussion: "How should photobook creation evolve in the next decade?" There are already some very interesting and challenging questions being raised and it would be good to get some more from eyecurious readers.

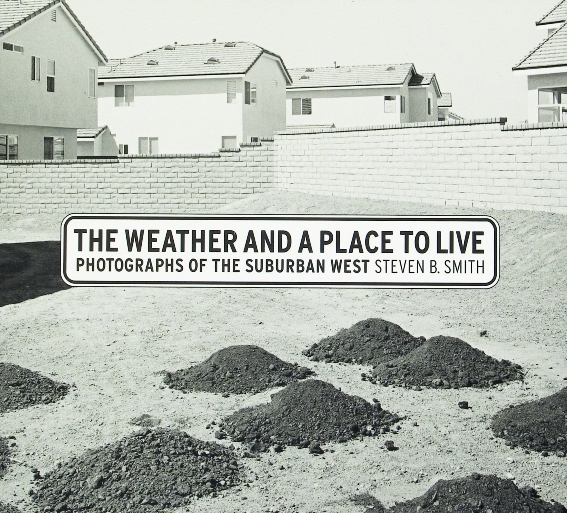

Review: Steven B. Smith, The Weather and a Place to Live

I wrote about Steven B Smith's series, The Weather and a Place to Live, in passing recently, but I've now got my hands on a copy of the book, which won the Center for Documentary Studies / Honickman First Book Prize in Photography in 2005, and have had the chance to have a more in-depth look.

The series focuses on the "American West", one of the great photographic subjects of both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The "American West"... for some reason the name itself sounds epic. Tackling this subject is no small undertaking, particularly given those that have done so in the past. Smith is clearly indebted to the New Topographics, the group of landscape photographers that featured in George Eastman House's seminal 1975 exhibition (Note: the show has been restaged this year and is currently traveling around the US before coming to Europe. I have just got a copy of the catalogue, so expect a review of this in the coming weeks).

The parallels with the New Topographics are obvious, but Smith's approach feels very much his own. He has focused in on one specific aspect of these landscapes, which is the mechanics of the steadily expanding suburban sprawl. Suburbia is being built at a furious pace and in many of these photographs it feels as if the dust has not yet had the time to settle.

Smith is not photographing a finished landscape, but one that is in rapid flux. This reminded me of Ryuji Miyamoto's concept of "temporary ruins" that he used to refer to the buildings that he photographed around Japan as they were being destroyed, only to be replaced almost instantly by a new structure of some kind (the series Architectural Apocalypse). Toshio Shibata's work on the complex infrastructure of Japan's roads occupies a similar space. His images also deal with a changing landscape, where extraordinary feats of engineering attempt to find some harmonious coexistence with nature.

The thing that I found differentiated Smith's work from these other series, and much of landscape photography in fact, is the emotional range of his images. This kind of work normally operates in a deadly serious register, oscillating between the beautiful and the ordinary, but almost always without emotion. I found that Smith's images treaded slightly different ground: they evoke fear, amazement, even sadness, but also a healthy does of humour at the ridiculousness of these manufactured landscapes.

Ridiculous is a word that kept coming to mind with these images. The ridiculousness of suburbia slowly taking over an area that is almost a universal symbol for wilderness: the American West. The ridiculousness of trying to trim and tame a landscape this wild and this epic in scale. Smith shows all of this with great subtlety and a wry sense of observation: there are few showy images here.

One thing I struggled with a bit in some of this work is the light. Smith sometimes shoots in very bright sunlight, which I imagine is typical weather for many of these locations, and so some of these images are almost bleached out, which I found distracting. Although this spoiled a couple of individual images for me, it does contribute to evoking the atmosphere of the place. And speaking of place, a special mention should go to the title of this series. As readers of eyecurious will know, titles have never been my forte, so I'm always impressed (jealous) when a title can encapsulate as much as this.

In some ways I felt that the first image of the book (below) could have been the last. It has the look and feel of a graveyard and suggests just how quickly the suburban landscapes that are being built here may fall into ruin.

The Weather and a Place to Live: Photographs of the Suburban West (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005, 128 pages, 80 duotone plates).

Rating: Recommended

Some things I bought this year

I've seen quite a few end of year lists popping up over the last week. There are the best books of 2009 lists, the more eclectic lists of "stuff I liked this year", the lists of books acquired in 2009 and many more. I think you need to be a breakfast-lunch-and-dinner kind of consumer of photo-books to post a best books of 2009 list and having just discovered a great many fantastic-looking ones through the future of photo-books discussion, I am not going to stick my neck out on that one. Instead in order to jump onto the list-mania bandwagon, I am going to go with a list of a few of the photo items that I bought in 2009 (these weren't necessarily made in 2009). Looking back over the year, I think this is an interesting way of seeing trends in the things that you gravitate to and also seeing how much money you wasted on things that you spend no time with at all.

Some photographic things that I bought in 2009

(Note: I am in a fortunate position where a number of books that come into my possession I don't actually have to pay for, so there are a number of terrific books that I discovered this year that won't make it on to this list)

Anders Petersen & J.H. Engström, From Back Home (Bokförlaget Max Ström, 2009)

This won the Author Book Award at Arles 2009. I posted a review a while back.

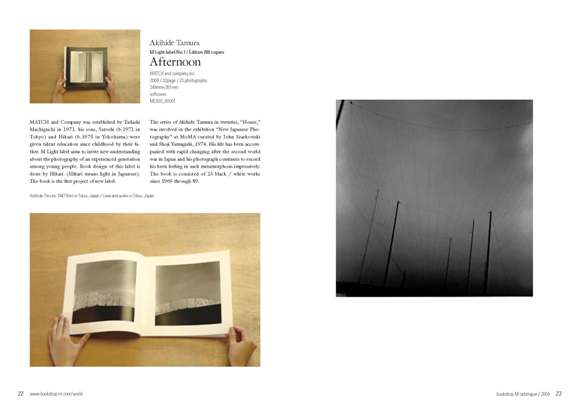

Akihide Tamura, Afternoon (M Light label No.1, 2009)

Although I just got this and have already posted about it, I get the feeling this is one that I will keep coming back to.

Ryuji Miyamoto, Cardboard Houses (signed, Bearlin, 2003)

Beierle + Keijser's "Becher box": Jogurtbecher

I have already spent the best part of an evening with E deciding what images we are going to use in our Jogurtbecher grid. And I actually hate yoghurt.

Michio Yamauchi, Stadt (Sokyu-sha, 1992)

Naoya Hatakeyama, A Bird (Taka Ishii, 2006)

OK I cheated, I didn't actually buy this, but this is probably the book that I have gone back to most frequently this year so it had to be included. Check out Jeff Ladd's review here to get an idea why.

Ikko Narahara, Pocket Tokyo (Creo, 1997)

Eikoh Hosoe, A Butterfly Dream (signed, Seigensha, 2006)

The extragavance of the year. This book was produced as a companion to the first edition of Kamaitachi. Hosoe presented it to Kazuo Ohno for his 100th birthday, shortly before his death. (As Michael rightly pointed out, Ohno is still around!)

Review: Andrew Phelps, Not Niigata

As soon as I heard the name of Andrew Phelps's latest book I was intrigued. Niigata is not the most obvious prefecture in Japan for a foreign photographer to choose as a photographic subject (Tokyo's magnetic pull certainly doesn't seem to be weakening). I was all the more interested as Niigata is an area of some importance in Japanese photographic history. One of the most important series of the postwar years, Yukiguni (Snow Land), was shot in Niigata by Hiroshi Hamaya. Hamaya was deeply interested in Japanese folklore and he chose Niigata as a photographic destination because of the many folk traditions and rituals that remained intact and revealed a 'traditional' Japanese way of life during a deeply troubled period where American occupation filled the vacuum left by years of militarism.

Phelps's Not Niigata is part of the European Eyes on Japan project that has been running every year since 1999 and which invites photographers who are working in Europe to "record for posterity images of the various prefectures of Japan on the theme of contemporary Japanese people and how they live their lives." This always seemed like an interesting photographic exercise to me, but after seeing some of the results in previous years it became clear how difficult it is. The participating photographers often only have a couple of weeks to photograph a specific region, which isn't a lot of time to try and get your bearings and come to terms with how things work in a country that is pretty radically different to Europe. One of the great strengths of Not Niigata is the fact that this difficulty is acknowledged from the outset. In his short introduction, Phelps writes:

"My way of working is a bit like making a poodle or a swan out of a shrub. Small bits of the mess are snipped away until some sort of form starts to take shape. (...) In the end if all goes well, I end up with something that may slightly resemble a poodle or a swan. But it's definitely neither a poodle or a swan and it's definitely not Niigata."

In some ways this project feels more like it is about the experience of going to a very foreign place for a very short time and trying to document ("for posterity") contemporary life, than it is about Niigata specifically. Phelps is very aware of this delicate position, as is obvious from the title of the book and even in the cover image, where a scene from Niigata is reflected with slight distortions on a pond or canal. This probably isn't the right comparison to make, but it reminded me in some ways of the film Lost in Translation, which isn't really about contemporary Japan, but about the feeling of being lost in a totally alien environment. I found that Phelps made subtle references to his position as a foreign photographer in some of these images, such as in this image of four children peering up at the strange gaijin who is taking their picture.

Phelps also successfully avoids reproducing exotic visual clichés of Japan or the Far East. In one image, he has photographed a tree that could have been silhouetted against the sky to produce an image that conforms to our vision of 'oriental' beauty. Instead Phelps has photographed the whole tree in a straightforward way and in the bottom right of the image he has left in a lamp post with two red spot lights on it.

He doesn't run away from the 'traditional' either: urban scenes that could well have been taken in Tokyo sit alongside images of two women dressed for a rice harvest festival or of an old woman sitting on a tatami mat in a traditional Japanese house. The overall picture that emerges from the picture is nuanced: we are shown old people, presumably in those rural areas that have been almost entirely abandoned by the young generation, and the young who hang out in modern cities that look like they could be anywhere in Japan. Natural beauty rubs up against modern anonymity and a certain sense of dilapidation. This Niigata does not feel like it has a bright future, but more like a place in limbo.

There are some great, understated, but astute images in this book. I found some of the portraits and the images of the more 'traditional' aspects of life in Niigata to be slightly less interesting. Overall I was left with a slight feeling of dissatisfaction, as I think Not Niigata would have been more successful if Phelps had developed more on this sense of displacement and alienation. But then I suppose that wouldn't be sticking to the script of the European Eyes on Japan project. Phelps feels like a very intelligent and thoughtful photographer and I look forward to seeing what his next project will be.

Not Niigata (Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag, 36 colour plates, hardcover, limited edition of 888 copies, 2009).

Rating: Recommended

Some more fuel on the photo-book fire

The debate about the future of photo-books is not exactly new, but it's not dying down either. I'm not sure where this particular strand of the debate started, but in recent days Jörg posted a few provocative thoughts over at Conscientious, which are feeding into a "crowd-sourced" blog post that has been set up by Andy from Flak Photo and Miki from liveBooks. So here are my two cents...

Firstly, there is the question of technology. This debate should be placed into the larger context of the debate on the future of books, period. This has been stirring up the publishing world for some time now and there are enough questions in that sphere to fill a book (pun intended), let alone this post, so I won't delve too deeply here (for some interesting insights check out this Monocle podcast that was done following this year's Frankfurt book fair). From what I have gathered, the general sense is that the e-book revolution is primarily going to affect non-illustrated books. Firstly there is the question of size: looking at a photobook, or most illustrated books for that matter, requires a certain scale. I can't imagine many people stuffing a photo-book sized Kindle in their pocket before they walk out the door. In addition there is a stronger affective and emotional relationship with illustrated books than with paperbacks: people relate to the book as object and not just simply to its content.

Another interesting indicator of the resilience of the book form is the amount of websites that try to replicate a printed publication format online. One example, Purpose, a pretty good online photo-mag based in France, is made to resemble a print magazine as much as possible, down to an optional fold in the center of the the online mag to give it more of a print feel. I think that once the possibilities of the web are explored further on their own terms and less in terms of what we are used to in print, there will be a greater recognition of how web and print do different things well and therefore of how complementary they can be.

The second aspect of this technological issue is the advent of relatively low-cost digital printing combined with the emergence of web 2.0 and print-on-demand sites such as Blurb that make it possible for pretty much anyone to print their own photobook (just as digital cameras made it possible for pretty much anyone to call themselves a photographer). In an already very niche market where print runs tend to sit between 1,000 to 2,000 copies for most photo-books, does it make sense to have specialised photobook publishers like Aperture, Hatje Cantz or Nazraeli or should people just do-it-themselves and then distribute thanks to the joys of the internet?

Although RJ Shaughnessy's Your Golden Opportunity Is Comeing Very Soon was a great example of DIYism, I think that photo-book publishers are essential and will not be going anywhere. Firstly, a quick survey of the posts about Blurb and co demonstrates that they have some way to go to convince professionals in terms of quality. There is nowhere near enough control afforded to you through these sites to be able to get the same result as you do with a printing house where much more fine-tuning is possible. They provide a great affordable and decent quality alternative to lugging a portfolio around with you or to test a book project concept, but for most fine art photographers, this isn't enough. Perhaps their most important function is to provide amateur photographers or pro-sumers (whatever the hell they are) with a terrific, inexpensive way of experiencing other aspects of photographic practice, such as sequencing, editing, graphic design and production, which is welcome in an age where millions of images are being produced every second.

This brings me on to Jörg's recent post, which laments the lack of adventurousness and experimentation in photo-book publishing and questions why we don't see more 'curated' books i.e. "books where someone does in book form what you usually see in a gallery or museum." Unfortunately in my (admittedly limited) experience of publishing, consistently squeezed profit margins and schedules means that editors are increasingly being replaced by or transformed into managers who only have time for a very cursory glance at the content of the books themselves. But if anything, the print-on-demand sites are likely to make things worse by leading to books with off-the-shelf design templates and which are produced in a limited number of standard formats. Worst of all, 99% of the time, there is no editor involved in the process.

There is an ongoing debate in the literary world surrounding how much of a debt Raymond Carver owes to his editor, Gordon Lish, for his signature sparse, economical, yet powerfully evocative style. Editors with this much creative influence are hard to find today, but they are no less important than in the past. Editors of photo-books are just as crucially important, particularly when it comes to reducing a series down to its essence and trimming off all excess fat. In such a small niche as fine art photography, they also have a huge general influence on the photographic landscape. To take my default example of Japan, Japanese photography would look very different if Shoji Yamagishi had not been around.

To go back to Jörg's point, it is true that most photo-books are monographs or exhibition catalogues, but this is only logical given that the sales of photo-books are so closely tied to exhibitions: there just would not be enough copies sold without them. In addition I think that these three forms (monograph, exhibition catalogue or collection catalogue) still offer a huge scope for experimentation. If anything, I think that the photo-book world may even be more experimental than the museum world at the moment. To illustrate my point here are a few examples that spring to mind.

Toluca Editions (that Mrs Deane posted about recently) have been around for a while on the Parisian photo scene, producing extremely high-end portfolios of work which are a collaboration between the artist, a writer and a designer. You could argue that these aren't strictly speaking books, but they are a great illustration of how far you can stretch the form. In a similar vein, but with a far more classic traditionalist feel, as part of my work with Studio Equis I have been collaborating with a Kyoto-based printing company, Benrido, that has combined nineteenth century colotype printing techniques with digital technology to produce a series of portfolios with truly exquisite results. Nazraeli are publishing a book next year in which Naoya Hatakeyama has collaborated with a French novelist, Sylvie Germain, who wrote a short story inspired from his series of underground images entitled Ciel Tombé. The book doesn't even exist yet, but this is an example of another way in which the photo-book form is being expanded beyond a group of images accompanied by descriptive text. Artists' books are another hugely rich field: on my last trip to Japan, Kikuji Kawada showed me a copy of the retrospective book he had produced (in an edition of 1) entirely with his own hands made up from several hundred digital prints painstakingly sequenced and hand bound into a mammoth encyclopaedic tome. To indulge in a bit of shameless self-promotion, I was able to get a study of postwar Japanese photography published by Flammarion in English and French at a time (2004) when virtually nothing had been published outside Japan on this period. I will stop there as this post is already far too long, but these examples are just the tip of the iceberg. You may need to go towards the fringes to find it, but experimentation in photo-books is alive and well.

The recent books on books (Parr and Badger, Errata Editions' Books on Books series and the recent Japanese photobooks of the 1960s and '70s) provide evidence that the importance of photo-books within photography is increasingly being recognised. The future looks pretty exciting from where I'm sitting.

Update:

- Jörg elaborated quite a bit on his original thoughts on the photobook subject and reacted to a number of the ideas in this post. Have a look.

- Darius Himes of Radius Books has also contributed to the photo-book discussion. As someone who actually has a real impact on what the future of photo-books will be, his thoughts are not to be missed.