The latest Vice Photo issue has just come out weighing in at a hefty 210 pages with images from everyone and his dog, including 'dirty old men' and Vice regulars Terry Richardson, Richard Kern and many others with some rather predictable results (sex, booze, drugs, androgyny, neo-hippyism, YOUTH) as well as some even-more-disgusting-than-before-but-strangely-compelling imagery from Asger Carlsen and one terrific little portfolio by Jason Fulford which stands head and shoulders above the rest in my view. Maybe this is a sign that I am turning into a nostalgic old man, but I have to admit that the thing that really excited me about this issue (and is the reason for this post) is that the cover (image by Jim Mangan above) is scratch-and-sniff. This is the first photo-publication I know of that uses this magical and sadly forgotten technique and for that, Vice magazine, I commend you. Choose from banana, cherry, coffee, weed, something called "Ocean Mist" and coconut (this last one isn't listed on the press release but I'm convinced it's in there, or at least that they printed the whole magazine on coconut-scented paper). Sadly this blogpost is not scratch-and-sniff (I can't believe there is no WordPress plugin for this), but the magazine is free so you have no reason not to go out and get a copy. Scratch-and-sniff everything forever.

I have no words for what I saw there

After the earthquake and subsequent tsunami struck the Tohoku region of region on 11 March 2011, the photographer Aichi Hirano decided to distribute 50 disposable cameras to the people in the shelters around Ishinomaki. He succeeded in retrieving 27 of these 50 cameras and subsequently published the results on a website created for the project www.rolls7.com This is a piece I wrote about the Rolls Tohoku project. It was first published in Foam magazine issue #27, 'Report', which has just been released (the issue is really an fascinating exploration of what reporting means in photography today... don't miss it). This summer the museum of photography in Stockholm, Fotografiska, will be exhibiting the Rolls Tohoku project from 7 July to 28 August. Rolls had a deep impact on me (as you will see from the following) and I urge you to take the time to spend some time looking at these photographs.

After the earthquake and subsequent tsunami struck the Tohoku region of region on 11 March 2011, the photographer Aichi Hirano decided to distribute 50 disposable cameras to the people in the shelters around Ishinomaki. He succeeded in retrieving 27 of these 50 cameras and subsequently published the results on a website created for the project www.rolls7.com This is a piece I wrote about the Rolls Tohoku project. It was first published in Foam magazine issue #27, 'Report', which has just been released (the issue is really an fascinating exploration of what reporting means in photography today... don't miss it). This summer the museum of photography in Stockholm, Fotografiska, will be exhibiting the Rolls Tohoku project from 7 July to 28 August. Rolls had a deep impact on me (as you will see from the following) and I urge you to take the time to spend some time looking at these photographs.

Update: a Japanese translation of the text is now available on Foam's website.

Japan lives with the constant threat of natural disasters. Located in a highly unstable sector of the Pacific Ring of Fire, it experiences hundreds, if not thousands of earthquakes every year and has become the best-prepared country in the world for quakes and the tsunamis which can follow. But nothing could have prepared the population for the gigantic quake and tsunami that devastated the Tohoku region of north-eastern Japan.

The earthquake and tsunami of 11 March 2011 was very likely the most highly-mediatized natural disaster ever. Although a large tsunami hit parts of Southeast Asia in 2004, very few images emerged of the brief moments of impact of the tsunami, but rather of the destruction that it left behind. Amateur footage was released in Japan shortly after the quake and within minutes the Japanese national broadcaster NHK sent helicopters out in anticipation of the tsunami that was expected to hit the Tohoku coastline. The resulting images showed the black wave swallowing everything in its path. Over the next few hours more footage was released, most of it shot by amateurs, showing the impact of the wave up and down the Tohoku coast. The spellbinding images, which played back on television and computer screens around the world, captured the brutal power and relentlessness of the tsunami. Some of the footage was also imbued with an eerie sense of dread as houses and cars floated down streets that had been full of activity just a few minutes before. The scale of the devastation quickly became apparent and, although the number of confirmed deaths was initially low, the images suggested that a huge death toll was inevitable.

Yet, within days the situation in Tohoku had all but disappeared from the international media as the troubling developments at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant began to monopolize the headlines. The towns of Minami Sanriku, Ishinomaki, Miyagi and Sendai that had been the center of attention until then receded into the shadow of Fukushima. A little over a week after the quake, I picked up a free newspaper on the Paris metro. The cover was a photograph of the Eiffel Tower on a hazy day, presumably taken weeks or months before. The headline read, ‘The Radioactive Cloud Arrives in France.’ The story had shifted from the tragedy that had befallen the people of Tohoku to the fear of what might happen to ‘us’. Within a week potassium iodide tablets had sold out as far away as Finland and the United States. Words like ‘meltdown’ or ‘radiation’ are so charged with meaning composited from science fiction and the very real horrors of Chernobyl or the fall-out from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that there was little space left in the collective imagination for scientific fact. As a narrative, the nuclear threat was infinitely more powerful: this was no longer just another tale of people’s suffering somewhere on the other side of the globe, but an invisible and very personal threat to each and every one of us.

Although, I have never lived in Japan I have visited the country regularly in recent years. My involvement with Japanese photography somehow made the events of 11 March feel deeply personal. In the days following the disaster I watched the news obsessively, hungry for any information at all, but finding very little. In the era of the 24-hour news cycle, information and stories are constantly recycled and updated, as the same images, the same tiny scraps of information get repeated over and over every hour. It was not until I heard the personal stories, of friends—a dear friend trapped in a bullet train in a freezing, pitch-black tunnel for over 24 hours and then travelling for two days to get back home, another who lost his mother to the giant wave and whose native town was totally destroyed—or indeed strangers—an 80-year-old woman and her grandson who survived together for nine days after the quake and who, when asked what he would like to be when he is older, replied ‘an artist’—that I was able to get beyond the huge, abstract idea of a natural disaster. As with these stories, the photographs in the Rolls project were the first that I saw that went beyond the surface of this tragic event.

When the earthquake hit on 11 March, a young photographer, Aichi Hirano, was showing his work in an exhibition entitled Rolls of One Week. Hirano explains, ‘At that time, I felt so powerless, being in the same country yet unable to do anything to reach out and help directly.’ To combat his sense of helplessness, he decided to distribute fifty disposable cameras to survivors displaced by the tsunami who had been evacuated to shelters in Ishinomaki, Miyagi prefecture. Hirano provided some loose directions on sheets of paper: ‘Please take photos of things you see with your eyes, things you want to record, remember, people near you, your loved ones, things you want to convey… please do so freely. And please enjoy the process if you can, even if it's just a little bit.’ Of the 50 cameras he distributed, Hirano was able to retrieve 27, which he uploaded in their entirety to the website www.rolls7.com

Until Rolls, most of the images emerging from the Tohoku region focused on the spectacular devastation caused by the tsunami – cars piled on top of houses, forests of debris where villages had once stood. In the face of disaster, when we cannot believe our eyes, photography has often been used to fill that breach: to provide a visual record that captures events so shocking or spectacular that they are impossible to digest. Perhaps the most powerful recent examples were taken from satellites. Several news websites created an interactive display superimposing a satellite image taken on 12 March over an image taken some time before the tsunami. By swiping across the image the user shifts between before and after, revealing the huge areas of land that had been wiped clean by the wave. Although images like these are undeniably powerful, they have a strangely impersonal quality. They provide a macro perspective of the disaster, a kind of quantification of the scale of the devastation, but one which gives us no insight into the individual lives of those affected. By contrast, Rolls offers a deeply personal vision of the disaster from the perspective of those who have been directly affected. These images do not just show the pain and suffering of the victims, but also their joy, their relief and even the boredom and tedium that they experience as they seek to pass the time in their evacuation shelters.

For each roll we know only the photographer’s name, sex and whether they are an adult or a child. But perhaps it is wrong to use the term ‘photographer’. The very point of these images is that they were taken by amateurs. In contrast to the spectacle of the images that appear in the press, there is little that is at all remarkable about these photographs. In one roll a boy has photographed his stuffed toys one by one on a mat. In another (anonymous) roll, a donkey appears tied to a tree that is just beginning to blossom. The rolls are made up of small fragments like these which we cannot understand beyond the knowledge that they are parts of individuals’ lives, details which to them seemed important enough to photograph. They do not employ the visual language of photo-reportage or of fine art photography to convey a specific message. Their quiet, artless, unselfconscious quality makes these images all the more powerful, investing them with the directness of words spoken by a young child. Although images of destruction are also present, it is not the subject of the photographs, but instead a visual backdrop to the ordinary details of these people’s lives. In one roll such images appear as blurry glimpses from the window of a moving car, as if the reality of the destruction had yet to sink in.

Hirano’s exhortation to the survivors to ‘enjoy the process if you can’ can be seen in the shots, particularly those taken by children. We see laughter, friendship, play – elements that do not appear in conventional images of disaster, but which provide a fuller picture of the reality of life in its aftermath. These are not photographs of what has happened to these people or images that construct a narrative that seeks to make the disaster understandable. Instead, they form a part of people’s ongoing struggle to digest and comprehend what they have experienced and, more simply, of the need to carry on with their lives.

During my short visit to Japan in early April a powerful aftershock struck the Miyagi region. At the time, I was with a friend in a bar in Tokyo, after having been to yozakura, the tradition of viewing the cherry blossoms by night. This was my first experience of an earthquake: the entire room swayed back and forth for a few seconds before the shock subsided. Although everyone stayed calm, not moving from their seats, the recent events made the tension palpable. We spent the next minutes anxiously watching television for news from Miyagi. My friend was aware of the damage this aftershock would cause, particularly as she was due to visit the area soon afterwards. A few days later I received a message in which she wrote, “I have no words for what I saw there.” This failure of words has its parallel in photography: rarely do images effectively describe an event of this magnitude. These rolls of film from Tohoku come closer than anything else I have seen yet.

What's Next?

I've just written a piece for the magazine European Photography in which I touch on the lack of substantial online discussion on current trends in photography and where things are going. I'll be posting the piece on eyecurious soon, so I won't go into detail here, but in general my feeling is that although online activity on photography is growing by the day, it is becoming commensurately shallower as a result. Fortunately there are examples which buck the trend. Foam, the Amsterdam photo-museum, has recently added What's Next? to its expanding range of content. What's Next? is a supplement to Foam's quarterly magazine but also an online discussion forum which is designed to spark discussion on current trends and how they are affecting the development of photography. The museum recently organised an expert meeting in Amsterdam around the What's Next project with an impressive line-up including Charlotte Cotton, Fred Ritchin, Thomas Ruff, Joachim Schmid and many others (you can see a number of the presentations from the meeting on Foam's youtube channel). Although the design of the site messes with my eyes and head a little bit, there is some terrific content on here running from photobooks to photojournalism. As a blogger I find that the most satisfying experiences writing online are those which spark a discussion, debate or even an argument. If you are interested in any of the above, I highly recommend a visit to What's Next?

Ganbatte Japan!

Interview: Christian Schink, A different kind of discovery

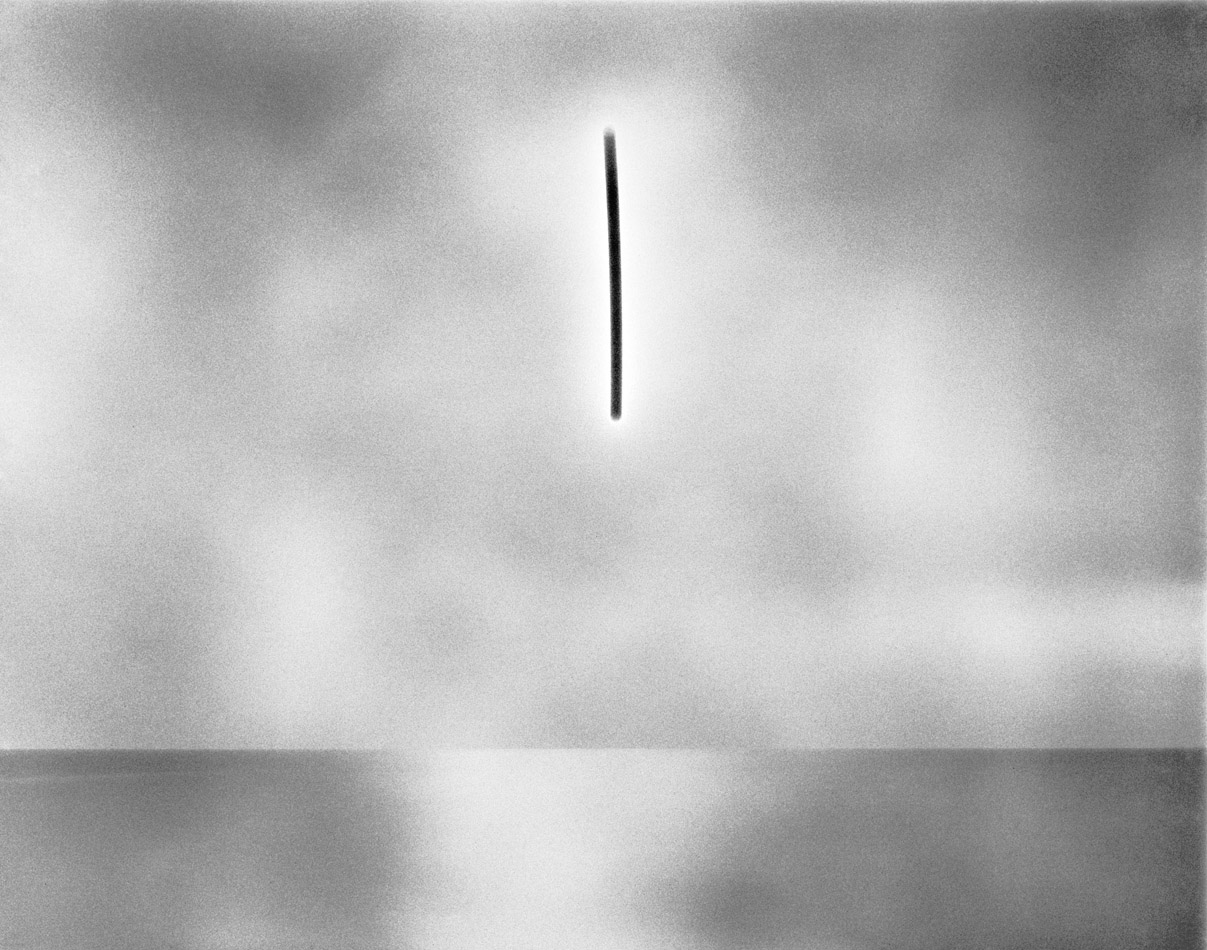

Hans-Christian Schink's latest series 1h is a real departure from the formal precision of much of his previous work and a delightful return to the essence of photography. The series has just been released in book form by Hatje Cantz (this one cannot have been easy to print!). Some of the works from 1h are currently on show at the Kicken Gallery in Berlin until 16 April. This interview was done for the latest issue (#6) of the excellent Fantom magazine based in Milan and New York.

Hans-Christian Schink's latest series 1h is a real departure from the formal precision of much of his previous work and a delightful return to the essence of photography. The series has just been released in book form by Hatje Cantz (this one cannot have been easy to print!). Some of the works from 1h are currently on show at the Kicken Gallery in Berlin until 16 April. This interview was done for the latest issue (#6) of the excellent Fantom magazine based in Milan and New York.

Marc Feustel: I'd like to start by asking you how the idea for this project first came about? It seems to be a significant departure from your previous work in terms of your visual approach.

Hans-Christian Schink: I first used solarization in one of my works in 1999 when I was invited to submit a work to the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Jena. I submitted a piece made up of three panels with abstract color gradations of a sky during the day, a sky at night, and the path of the sun, which appears as a solarized, black line on a white background. I got the idea from a Hermann Krone photograph from 1888. Unlike Krone, I pointed my camera straight at the sky in order to get a clean, linear image of the sun. I didn't pursue this theme at the time as I was focusing entirely on my series Verkehrsprojekte Deutsche Einheit (Traffic Projects German Unity). Later, on a trip to the Mojave Desert in California in 2003, I was so fascinated by the landscape and the blazing light that I wanted to find a way of reproducing this almost unreal impression. I remembered Minor White’s photo, Black Sun, of a winter landscape where the sun appears as a solarized black dot—an accidental effect created when the camera shutter briefly froze. I wanted to try to use this effect with a longer exposure, but I wasn’t sure if any of the landscape would be recognizable at all. I didn't work persistently on the idea at the time: I was busy with other projects and wasn't sure that it was possible to construct a solid concept from what was quite an atypical approach for me. I was also still dealing with different technical and contextual issues. Most importantly, though, I wasn't sure that the project could become something more than a technical game.

MF: What was it that convinced you could turn the project into something more than a technical exercise?

H-CS: It was a question of the atmospheric power of the image. To me, the Hermann Krone picture was the document of an experiment: it only contains the line of the sun and a faded rooftop silhouette. My first test photos didn't look very different. But when I found a way to balance out the aesthetic power of the landscape with the dominating phenomenon of this mystical black line, I knew it would work.

MF: The project seems to deal with the very essence of photography: drawing with light. These sun traces seem like the most primitive manifestation possible of this. Was this project a way for you to explore the basic components of photography, light and time?

H-CS: Yes, absolutely. And in a very unusual, almost abstract way. I was able to reproduce the light of the sun and the passage of time without them being recognizable as such at first glance. The pictures show a completely different reality of their own that can only be perceived through photography. This touches on one of the key issues of the medium: the ability to depict reality.

MF: The relationship to reality is a very interesting component of these photographs. Although the landscapes are real, the black trace of the sun makes us question the reality of these images. In general, it seems that photography's link to reality has become more and more hazy with technological developments in recent years. Do you think that people would still be as attached to photography if it were no longer perceived as a document of reality?

H-CS: I don't think of photographs as documents of reality. Even if they are taken from reality, to me photographs are beyond reality, in either a positive or negative sense. Looking at hundreds of holiday snapshots taken with enthusiasm during a trip to an exotic location, you will most likely realize that these images do not translate the atmosphere of that place at all. Your own experience of reality is far from what's depicted in a photograph. On the other hand, in a photograph as a work of art you will always find more than you can actually see in the picture. It will create it's own kind of reality.

Of course, the presumed link to reality is still one of the most important aspects in photography. Even if we know that a "photographic" image is completely digitally composed, it somehow appears to be a document of reality. It's a matter of perception versus knowledge and I don't think this tension is going to weaken.

MF: I’m interested in the very particular aesthetic of the images. The long exposures give the pictures a very particular feel, like faded nineteenth century travel photographs where the chemistry has changed over time. Did you have something specific in mind when you started or was this just the result of the complicated long exposure process?

H-CS: It was a result of the process. I just needed to understand that this particular aesthetic is essential to the work. I realized that the technical imperfection was a benefit, not a drawback, that it gives a certain 'back-to-basics' impression. The whole project was about accepting conditions that were completely different from my previous projects.

MF: The black trace of the sun has a great democratising power. All of the landscapes, no matter how dramatic, beautiful or iconic appear to be dwarfed by this primitive trace or scar in the sky. The chemical inversion of sunlight from white to black also seems to reverse the properties of the sun. It is no longer life-giving, warm or nourishing, but rather becomes brutal, stark, and even creates a sense of melancholy.

H-CS: I agree and I'm quite happy that the results turned out that way because that was what I was hoping for. Though, one of the many ambiguous aspects of this project is that the atmosphere of the image is so different from the one when taking the picture. The hours I spent waiting next to the camera, often just observing the landscape while the sun did its job, were fascinatingly intense, sometimes unforgettable experiences… among the best experiences I’ve had in my work up to now.

MF: How did you decide on the 1h timeframe for the exposures?

H-CS: I started with timeframes of 10, 20 and 30 minutes, always curious as to the effect this extreme overexposure would have on the visibility of the landscape in the picture. I was surprised by the results and so I finally settled on an exposure time of one hour, since it’s the most commonly used unit of time. Dividing time is the human way to deal with eternity.

MF: I’m interested in the disconnect between these photographs and your experience when capturing these images. Of course you cannot look directly at the sun, let alone watch it inscribe its path in the sky over one hour. Can you describe your experience observing these landscapes while waiting for your camera to capture the trace of the sun?

H-CS: At the early stage of the project I always felt a little nervous during the one hour of exposure time, concerned about the result. Over time I learned to accept that once the cameras are set, the result would be beyond my power anyway. Given this, I became much more relaxed. I developed a kind of laid-back stoicism and was able to enjoy the situation, to enjoy the sunlight, which was of course warm and nourishing then. Even at locations in L.A. or Tokyo for me there was this atmosphere of calm and quietness. And in some particular places like in the Algerian or Namibian desert this experience became really amazing. There were moments of contemplation when I started to sympathize with the idea of worshipping the sun.

MF: When you began the project in the Mojave desert I believe that you initially intended to shoot it in a single location. What made you decide to extend the project across the globe?

H-CS: One of the most fascinating aspects of the experimental phase before I actually started the project was exploring how the angles of the sun line varied according to the latitude of each location. As a result of this variation, I decided to expand the project to cover the whole world and therefore began checking to see if the destinations I had already selected would be suitable locations for this series. At the same time I also started looking for places that fulfilled certain criteria, for example I wanted a photo from the northernmost and southernmost points that could be reached with a reasonable amount of effort. I also wanted a picture of the midnight sun, photos from places along the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn taken during the solstice, a picture shot from as close to the equator as I could get, and one taken along the International Date Line.

MF: The sun is a universal symbol which has deep cultural and religious connotations that differ around the world. Was this something that you considered in choosing the different locations?

H-CS: Yes, in the beginning. Actually I was thinking of going to Egypt for example, but then it would have been almost impossible to avoid photographing at locations related to the sun as a religious symbol. The next question would have been why choosing only one specific location since there are so many other sun-related places all over the world. The focus would have turned too much to human culture and religion.

MF: You chose to focus not only on natural landscapes but also on some urban locations. What made you decide to include these cityscapes alongside the more dramatic natural landscapes in the series?

H-CS: It was important for me to show that this phenomenon occurs everywhere, not only in landscapes far from civilization. The power of the sun is present all over the globe. However, it was extremely difficult to find urban settings with no visible "life", with no or few people, no cars going by in front of the camera causing reflections that would have distracted the viewer's eyes from the line of the sun. In the beginning I also photographed in places that were easily recognisable, such as Downtown L.A. or the Reichstag in Berlin, but finally decided not to use them, for the same reason.

MF: You have referred to the connection of this project to nineteenth century travel photography. Today it seems that the sense of discovery in travel has all but disappeared, there are virtually no places left to discover. I was struck by the fact that your series revives the sense of discovery by showing us the world in a way that cannot be seen by the naked eye.

H-CS: It's a different kind of discovery. I like the idea that this discovery can take place everywhere, you don't even have to travel to experience it. But I did, and it was my goal to show the world in a way that cannot be seen by human eyes.

MF: In the book, you include a map detailing the itinerary that you took to shoot the series. I was interested in the fragmented nature of this journey: it is not a round the world trip but a series of individual trips which extend out over time from your home in Germany. How important was the journey process for you in making this series?

H-CS: The final journey I made to complete the project was actually a three-month around-the-world trip. After all the single trips undertaken to get to a particular destination I thought it would made sense for the final journey to literally follow the sun on its way around the earth. Knowing the facts of modern astronomy, I think this geocentric perspective is still the way we look at this phenomenon up in the sky.

MF: The captions to your images provide details of the date, exposure time and coordinates where the image was taken. This information is at once very specific, scientific even, and yet it reveals nothing to us about the subject or location of the photographs. Why did you decide to use this information for the captions and to omit the names of the places where you were taking these photographs?

H-CS: Since the photos are not about the individual locations per se, I decided not to mention the places in the title, because they would always evoke some sort of visual association. I also like the contradiction between the fact that the title of each work gives the most precise information possible about the location but nobody knows where it is. We still rely on names to imagine a place, even if our imaginations don't reflect the reality of that place. I also enjoy the contradiction between the fact that the images seem to show something completely beyond human control, something out of this world, but if you check the coordinates with Google Earth, within a few seconds you're looking down from above like a god on the exact place where the picture was taken.