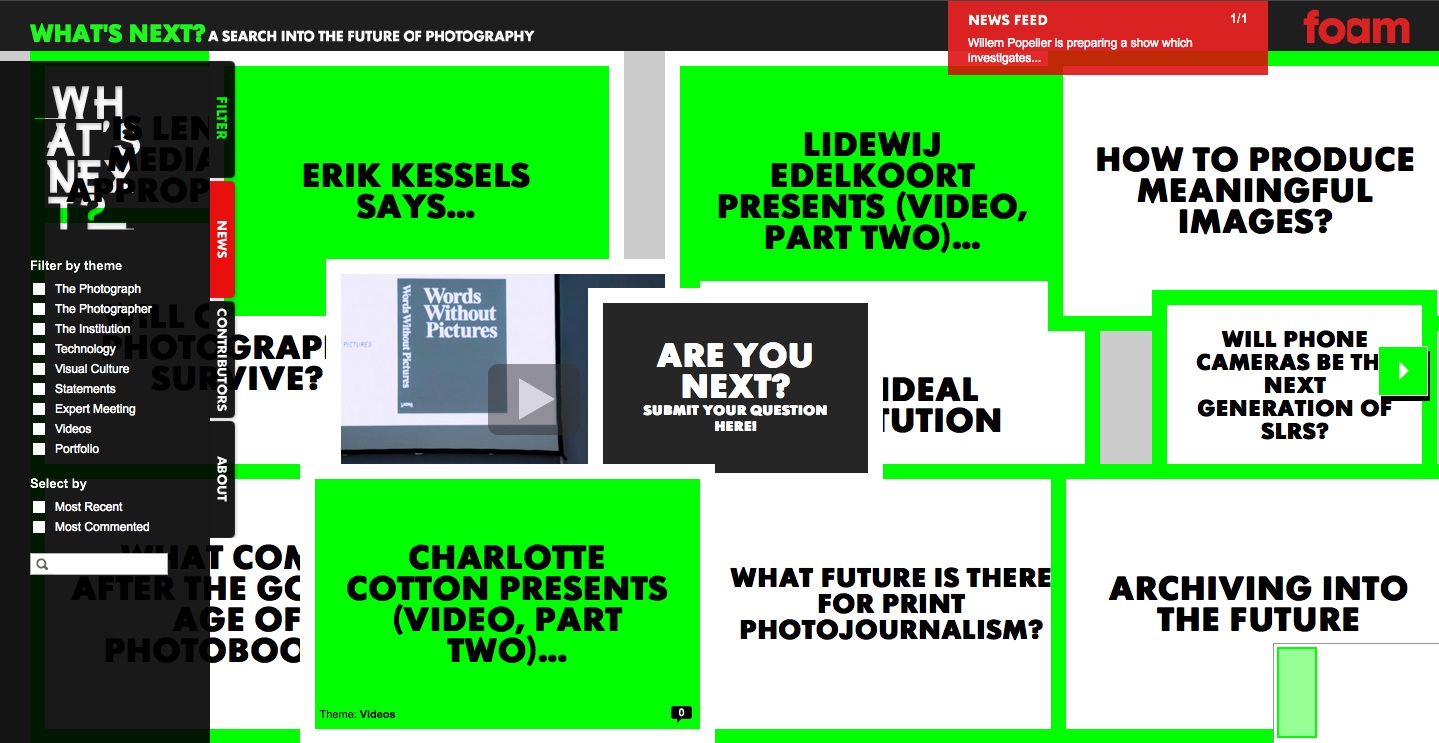

I've just written a piece for the magazine European Photography in which I touch on the lack of substantial online discussion on current trends in photography and where things are going. I'll be posting the piece on eyecurious soon, so I won't go into detail here, but in general my feeling is that although online activity on photography is growing by the day, it is becoming commensurately shallower as a result. Fortunately there are examples which buck the trend. Foam, the Amsterdam photo-museum, has recently added What's Next? to its expanding range of content. What's Next? is a supplement to Foam's quarterly magazine but also an online discussion forum which is designed to spark discussion on current trends and how they are affecting the development of photography. The museum recently organised an expert meeting in Amsterdam around the What's Next project with an impressive line-up including Charlotte Cotton, Fred Ritchin, Thomas Ruff, Joachim Schmid and many others (you can see a number of the presentations from the meeting on Foam's youtube channel). Although the design of the site messes with my eyes and head a little bit, there is some terrific content on here running from photobooks to photojournalism. As a blogger I find that the most satisfying experiences writing online are those which spark a discussion, debate or even an argument. If you are interested in any of the above, I highly recommend a visit to What's Next?

Notes on 2010

As the year draws to an end and more top-10 lists (and non-lists) than you can wave a stick at make their annual appearance, I thought I would take a broader look back at the past year in photography. This time last year I focused on the chronic over-use of the word curating, a trend which shows no signs of abating. As for 2010, the major development in the world of photography has to be the exponential rise of the self-published and independent photobook.

As the year draws to an end and more top-10 lists (and non-lists) than you can wave a stick at make their annual appearance, I thought I would take a broader look back at the past year in photography. This time last year I focused on the chronic over-use of the word curating, a trend which shows no signs of abating. As for 2010, the major development in the world of photography has to be the exponential rise of the self-published and independent photobook.

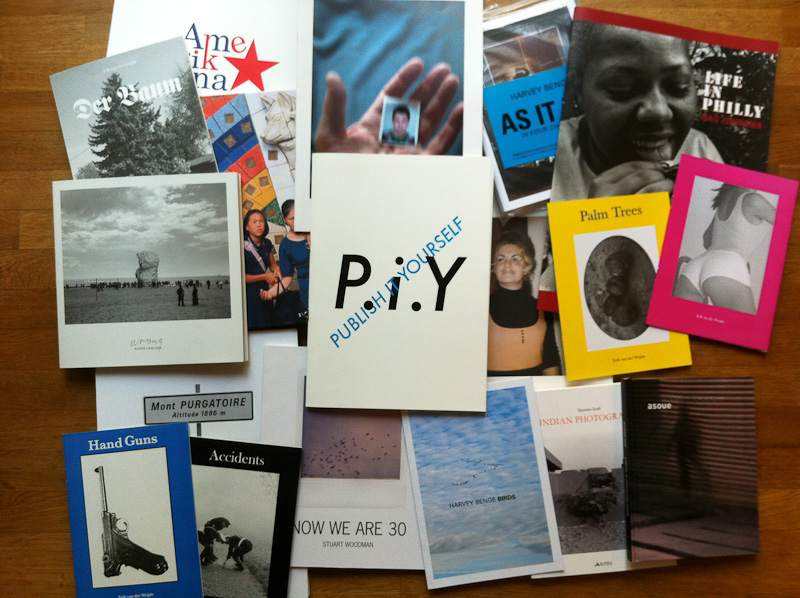

This year has seen the launch of Alec Soth's Little Brown Mushroom (LBM actually launched in December 2009, Soth once again proving that he is ahead of the curve), the online listings database The Independent Photobook, the Indie Photobook Library, the Off Print photobook festival in Paris, a big online discussion on the future of photobooks and (perhaps another sign of Soth's prescience) the growth of countless independent publishers like so many little brown mushrooms. This frenzy of activity wasn't only limited to the periphery either: the (deserving) winner of this year's book prize at the Rencontres d'Arles was an independent publisher from Berlin, Only Photography, for Yutaka Takanashi: Photography 1965-74. If there were any doubts remaining as to the importance of this trend in 2010, while writing this paragraph I received an email from yet another freshly-launched website devoted to the self- and independently-published photobook. I think this explosion in 'indie' publishing is a great thing, particularly given what was being said about the future of photobook publishing a couple of years ago. However, although we have learned that publishing it yourself can make you happy, it can also make you very confused, even overwhelmed. It is truly amazing how many photobooks are being made now, far too many for one poor blogger to even begin to get his head around and (surely?) far too many to sell to a very limited pool of buyers. The problem is that only a very small percentage of them are any good. By good I don't mean "containing good photography" but rather good as a stand-alone artwork where the design and production matches, or even enhances the content rather than a brochure for a series of photographs. Not every series of photographs deserves (or is suited) to becoming a book. Hopefully the publishing effervescence of 2010 will give way to a 'more quality less quantity' scenario in 2011.

Another phenomenon that has accompanied this rise in self- or indie publishing is the rise in luxury, super exclusive, VIP, signed, numbered and sealed-with-a-kiss editions. Despite the rise in the number of photobooks being published, only an infinitesimal number of these make any money and publishers are still searching for the winning formula. Rather than the 'limited' print runs of the past (700 to 1,000) it seems that a number of publishers are moving towards deluxe extra-limited editions (100 to 500). To mention just a few examples Germany's Only Photography and White Press are both producing books which will generally set you back at least 80 euros ($100), and in the US Nazraeli Press has completed ten years of its One Picture Book series where (for $150) you get a small original print thrown in with the eight or nine plates in the book itself. One final publishing trend worth noting is the growing number of re-editions of classic photobooks. In addition to Errata Editions' full series of books on books, this year we were treated to a range of re-editions from Takuma Nakahira's A Language To Come to John Gossage's The Pond. Given how much the originals are sell for at auction these days, I'm grateful to be able to get my hands on some classics without having to sell all the other books I own in the process.

And what of photography itself in 2010? Looking beyond the book, this year feels far less exciting. As with the rest of the art world, photography galleries are still gently and nervously probing the market with little space given to new or 'difficult' work, while museums are staying well away from anything risky with big-name blockbuster retrospectives, shows assembled from their own collections (which is not necessarily a bad thing), or shows lasting from 4-5 months instead of 2 or 3. Just as with books we're also seeing the reedition of landmark exhibitions, with the New Topographics show touring the US this year. In terms of museum shows a special mention has to go to two examples of ludicrous censorship: the recent removal of a video by the artist David Wojnarowicz from the exhibition "Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture" at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington after the Catholic League and members of Congress complained that the piece was sacrilegious due to a sequence showing ants crawling on a crucifix, and the Paris Museum of Modern Art's Larry Clark exhibition which got itself an X-rating from the government and therefore a shed-load of media attention.

On a positive note, a more interesting trend has been the use of Google Street View by several artists as a new photographic tool. Michael Wolf (see the grid below), Doug Rickard and Jon Rafman have produced exhibitions, books and tumblrs of images taken from Google Street View's online tool. This is clearly not everyone's cup of tea and, particularly in street photography circles, there tends to be a "that is not photography" response to this kind of work. Whether you like it or not, it raises a number of interesting and important questions about the way the practice of photography and the hypocritical rules governing it are evolving .

Another technology-related trend has to be the massive growth of online social networking in the photo community. Of course this is a phenomenon that is by no means limited to photography, but it is astounding how quickly Facebook has gone from an interactive high-school yearbook to a major marketing tool (alongside its younger cousin Twitter). Some have even used it as a tool through which to publish a series of photographs steadily over time. I'm not sure how this is going to affect photography (if at all) and others have thought about this harder than I have, but it will be interesting to see where this goes in 2011.

Finally, I get the feeling that there is a bit of a reemergence of street photography going on. With in-public's 10 (review here) and Sophie Howarth and Stephen McLaren's Street Photography Now. This may be because we're all photographers now and the most obvious place to start is the street, or perhaps because people are growing tired of the cold, detached formalism that has dominated recent contemporary photography, or maybe even the fact that the abuse of anti-terrorism and privacy laws is making it more and more difficult to photograph in many of our cities and that street photographer's tend to like a challenge.

To wrap up this look back at 2010 (despite last year's rant) seeing as we all love lists (because we don't want to die), here are a few highlights from the past year in no particular order:

- The opening of LE BAL in Paris and its first exhibition Anonymes

- Discovering Leo Rubinfein's A Map of the East at the Comptoir de l'Image

- The outdoor installation of Michael Wolf's Paris Street View work in Amsterdam

- Meeting the wonderful Mao Ishikawa at Paris Photo

- Erik van der Weijde and Harvey Benge's relentless (and extremely good) book-making

- Completing my first 3-day portfolio review marathon at FotoFest Paris

- Foam magazine's excellent new (and free!) 'What's Next' supplement which takes a look at the future of photography through some very interesting pairs of eyes

Interview: Chris Engman, Freedom, possibility and a desire for purity

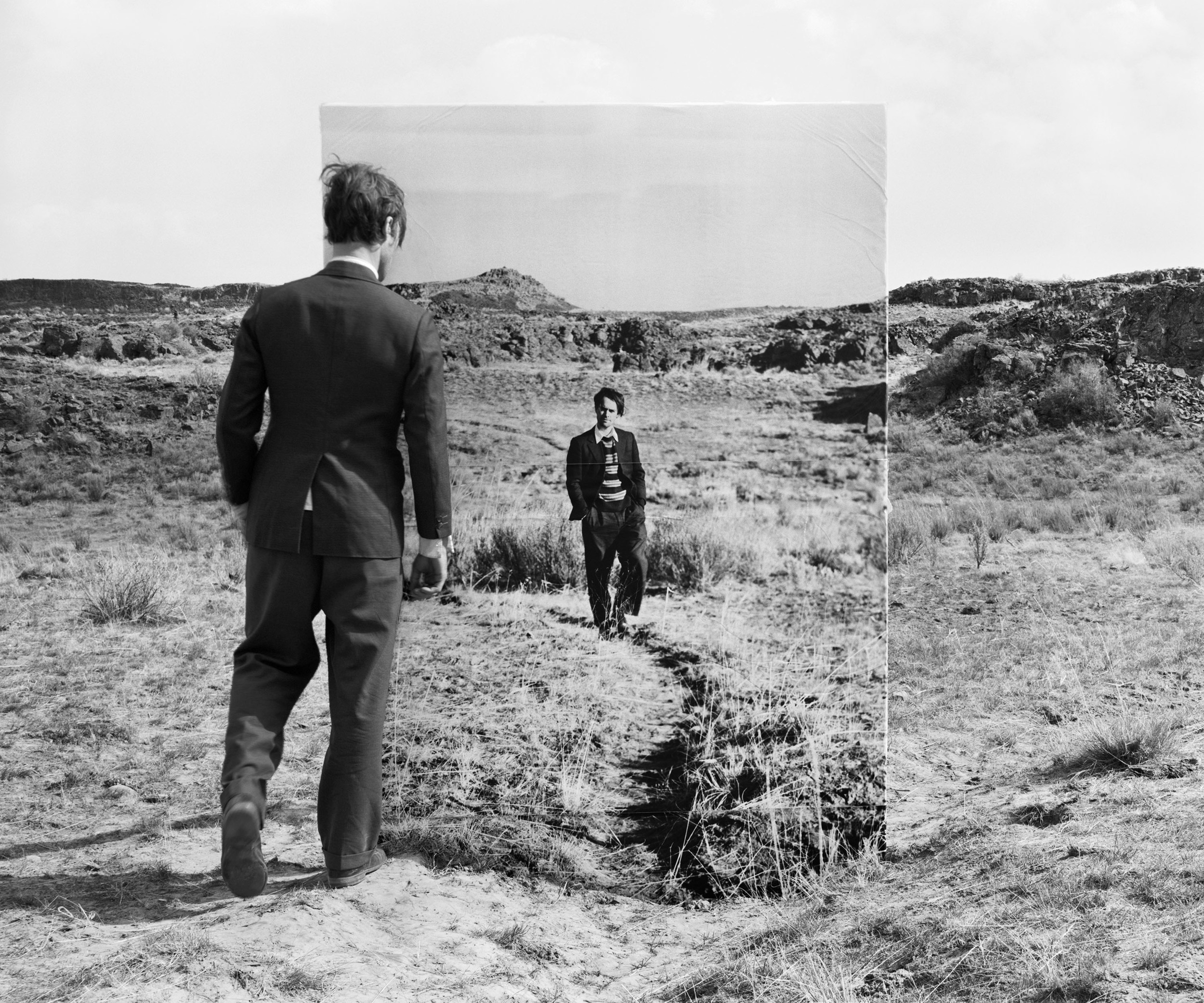

Chris Engman's series Landscapes is based on the vast open spaces of Washington State outside of Seattle, where Engman lives. The title of the series, just like the images themselves, suggests one thing, while revealing many others. He has a show on at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle until Christmas Eve 2010. This interview with Engman was done for the Talent Issue (#24) of Foam magazine which came out in September 2010.

Chris Engman's series Landscapes is based on the vast open spaces of Washington State outside of Seattle, where Engman lives. The title of the series, just like the images themselves, suggests one thing, while revealing many others. He has a show on at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle until Christmas Eve 2010. This interview with Engman was done for the Talent Issue (#24) of Foam magazine which came out in September 2010.

Marc Feustel: What attracted you to the landscapes of eastern Washington that you use for your photographs?

Chris Engman: When I set out to make a photograph I begin with an idea. I write about it, turn it over in my mind, and gradually the requirements for a site take shape. I then go out and drive, sometimes for a long time, until I find that site. The idea is not a response to the landscape; in my work the landscape is a response to the idea. Once I’ve found and used a site I become attached to it, and there are some that I frequently revisit. They go from being spaces where I am free to let my imagination wander to being places with a personal history and familiarity. I have dreams about buying up all that land and doing nothing with it so that it will be left alone.

MF: You refer to these landscapes as resembling ‘an unformed dream or empty canvas waiting to be acted upon.’ What made you want to intervene in these landscapes?

CE: They fulfilled the requirements for the illustration of my ideas. When I refer to these spaces as an empty canvas I mean that they are relatively free from distracting associations, so that the work can just be the work. Undeveloped land, ocean views, deserts, the associations they have are ones that are appropriate to the work: freedom, possibility and a desire for purity.

MF: The Japanese photographer Naoya Hatakeyama has suggested that ‘nature is already so distant from us that you might say it has become a fantasy’. Is this an idea that resonates with you?

CE: I don’t personally feel more distant from nature than I want to be. My work affords me a lot of opportunities to be in nature and for adventure and misadventure. Being and working in extreme places connects me to nature by confirming the power it has over me. I don’t really imagine that there is such a strict division between man and nature. We are a part of nature, when we harm it we harm ourselves.

MF: Can you describe how you go about constructing your images? The process seems quite elaborate.

CE: Every image presents unique challenges. In the case of Equivalence, to begin with I found a suitable piece of private land and got permission to use it. I built a frame and photographed it. Back in Seattle I made fifteen large prints altogether measuring 4.5 meters wide and over 3.5 meters high. The prints had to be skewed digitally to account for the fact that the frame was not parallel to the film plane. I returned to eastern Washington and placed the prints back onto the same frame. In the final photograph you wouldn’t know by looking at it that the prints were ever skewed be cause the camera, replaced to its original location, skews them again back into ‘correct’ perspective. The piece is titled after the series of clouds by Alfred Stieglitz, in which he suggests that his images of clouds can represent inner states and emotions. My version asserts that photographs are not objective and can only ever tell partial truths, and beauty and emotion are constructs of the mind. For me this doesn’t lessen photography, beauty or emotion but makes them all the more interesting.

MF: Manipulation in photography is not new, but digital technology has extended the range of possibilities and the line between straight and manipulated photographs is increasingly blurry. Do you think people’s perceptions of what a photograph is are changing as a result?

CE: One question I get a lot is are they manipulated? The answer is supposed to be no, they are ‘real.’ This is a false dichotomy. All forms of representation are manipulation. But the question gets asked, and at the root of it is a desire for authenticity. What needs to be better understood is that sometimes even heavily manipulated images are truthful and sometimes straight photographs tell lies, so there should be a different set of criteria for authenticity. My own photographs are in many ways closer to what is meant by straight than not. That is, the majority of the digital manipulation that I do could have, at least theoretically, been done in a darkroom. However, I have no qualms about crossing that line when necessary. In The Haul, for example, street signs and text on the buildings have been removed so that the place would have a more generic quality. One thing I will not do is pretend I did something that I did not do. Many photographers are finding ways to make their work be less work, while I have gone in the opposite direction. My photographs are laboured, and they don’t take short cuts. In that sense I am like a sculptor or installation artist who uses photography as a tool.

MF: I am curious to know about your influences and in particular your relationship to landscape photography. Your work occupies quite a unique space and it seems to integrate many different photographic and artistic traditions.

CE: I think a lot about Robert Smithson’s work relating to time and place. The Earthworks artists often have more in common with my process and practice than do landscape photographers. I enjoy the work of Michael Heizer and Walter De Maria, Georges Rousse and Robert Irwin. The re-photographic work of Mark Klett has been an influence recently. Fiction by writers such as Milan Kundera, Salman Rushdie, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Faulkner and Hemingway often directly spurs ideas for particular photographs. Also the writings of the neurologist Oliver Sacks are an influence.

MF: As opposed to many contemporary landscape photographers your photographs don’t seem to have a direct message about the relationship between man and nature. Do you consider that there is a political aspect to your work?

CE: I am a political person but my work is not directly political. A lot of contemporary landscape photography is concerned with human exploitation of the landscape, usually with a pessimistic or nostalgic undertone. Although I am of course concerned about exploitation, the subject of my work concerns abstract ideas relating to perception and the human condition. On the other hand a few of my works do contain some subtle social criticism. One way to read The Haul, for example, is as a questioning of consumerism and the ideas about success that drive us to always want more and do more and never be content. The piece expresses a desire to travel through life with a lighter load.

MF: What are you working on at the moment?

CE: The piece I’m working on is a diptych called Dust to Dust. My plan is to find or make a large pile of sand or dirt and photograph it. For the second part of the diptych I will employ land-moving equipment to rotate the pile ninety degrees clockwise. The mountain of dirt will be reformed in its original shape, the shadows will be repeated with careful timing and camera placement. In this way the pile of dirt will appear to remain stationary while the landscape itself will appear to have moved. The piece is a meditation on impermanence and the fact that not only existence but even the features of the physical world are temporal and will come to an end.

Apologies and explanations

Once again, dear readers, I have to apologise for my blogging silence. But this time I have a pretty foolproof excuse (see image above).

In fairness I can't blame my recent wedding entirely for the lack of posting as there is another happy event that has kept me busy for the other half of the summer: FOAM magazine's annual Talent issue. I was asked to do all the Q&As with the fifteen contributing photographers, which was an excellent experience as there are never enough opportunities to sit down with photographers and ask them a bunch of questions about their work and a lot of the work featured in this issue I would most likely never have discovered otherwise. With photo-blogs I find that we too often just gravitate towards things that we take an instant liking to and too often end up overlooking interesting work that doesn't immediately resonate with us, so being presented with a really broad cross-section of work from all different fields and styles and trying to engage with all of it is an experience that I highly recommend. As a bonus, I'm not the only blogger to feature in the issue, as I understand that Mrs Deane has also contributed a text... two virtual salmon swimming upstream into the world of the printed page. The magazine is going to be released this week so keep an eye out for it at your local photobook store. And more to the point, keep an eye out here as eyecurious gets cranked back into action.

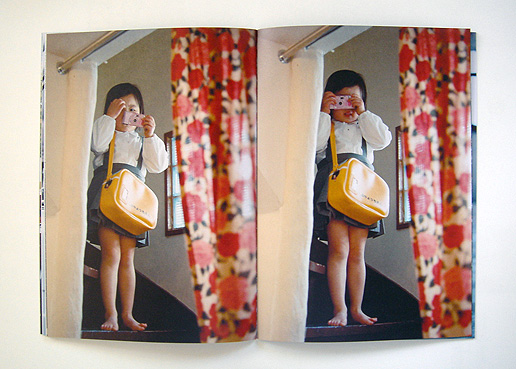

Takashi Homma: Adrift in the city of superflat

Self-promo alert: I've just written an essay on Takashi Homma's series, Tokyo and my Daughter, for edition 23 of FOAM Magazine on City Life. Of course this brilliant piece of writing is reason enough to buy yourself a copy, but there happens to be some other really good stuff in there too, so now you really have no excuse.

Self-promo alert: I've just written an essay on Takashi Homma's series, Tokyo and my Daughter, for edition 23 of FOAM Magazine on City Life. Of course this brilliant piece of writing is reason enough to buy yourself a copy, but there happens to be some other really good stuff in there too, so now you really have no excuse.