Just as Google launches, Google+, it's latest attempt at a social network and an attempt to lure people away from Facebook, I thought I would share a piece that I have written for the latest issue of European Photography (which comes out today) that deals with the impact of blogs and social networks on the way we consume and understand photography. If you are interested in looking further into the online photography world I also recommend checking out the previous issue of European Photography (no. 88) on 'Net Photography' which investigates some of the trends in photography that is being produced specifically for and distributed through the web. Blogs have always been fragile creatures: statistics show that around 70% of them die within their first month. And now, only a decade after they first appeared, some are concerned that they are becoming an endangered species. While I am relatively new to blogging (I started eyecurious in April 2009), even in my short virtual lifetime a lot has changed. Particularly in the last year, a significant part of the online activity relating to photography has moved to online social networks such as Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr. So are we witnessing the demise of the blog? As with most of these dichotomous debates linked to technology (printed versus digital books, analog versus digital photography, etc.) I think the question is not so much whether (or when) the new will kill off the old, but rather how they are influencing each other. More specifically, what impact is the rise of social networks having on the online conversation on photography?

In a recent piece Andy Adams summarised the impact of blogs and social networks as follows, “web 2.0 is influencing contemporary photo culture around the world by connecting international audiences to art experiences, enabling the discovery of new work and presenting never-before-seen channels of expression and communication.” Blogs, webzines and now social networks have made photography far more accessible than before. We are no longer dependent on museums, galleries and books for photographic content. This not only makes it cheaper and easier to get our hands on photographs, but we can now see far more images than are available through these ‘traditional’ forms. The web makes it just as easy to access photographs being made outside our front door as on the other side of the globe, as well as work that has yet to be exhibited or published and often never will.

What truly characterises web 2.0 however is participation: the opportunity for everyone to share information and to get involved in a conversation. Although I think the internet is at its best when it creates discussion and debate, the vast majority of online activity still centres around the dissemination of information. Even within a tiny universe such as the ‘fine art photography’ (for want of a better term) community, the accessibility of the web quickly leads to an overwhelming amount of photographic content. Blogs, online magazines and increasingly social networks act as filters, allowing people to more easily find the content that most interests them. Social networks have further refined this process, not only making it easier to find the kind of photography we want, but also providing a platform on which to have a conversation around photographs. These networks create spaces for discussion around specific topics or fields of interest that just aren’t possible on the infinite plain of the broader world wide web.

So what is the downside? Most of us would agree that better access and more conversation sounds like a pretty good thing. However, while these online developments have been leading to more conversation, I would argue that they have also been making it more shallow. Take the example of Facebook. While the platform does allow for discussion, the structure of the Facebook platform is such that we are constantly being asked to like things, whether it be through ‘Fan Pages’ or simply by choosing to ‘Like’ something that someone else has posted. While I don’t think a ‘Dislike’ button would add anything to the quality of the online conversation, it would at least remind us that our reactions to photography don’t all have to be situated on scale running from good to awesome.

Twitter is a slightly different beast. With its 140-character limit, the network is intrinsically suited to point towards existing information rather than to create new content. Even in the case where a conversation develops between several users (‘tweet chats’ in the local jargon), the medium is entirely focused on immediacy and not on considered opinion. By the time you have finished reading a tweet there are already several others that have appeared in your Twitter feed demanding your attention.

The reason this matters to photography is that it can lead to a situation where we are constantly consuming and never digesting. The danger with the infinite accessibility of the web is that we can find ourselves only looking at photographs that are immediately seductive or simply popular in the networks around us. Work that might be deemed quiet, challenging or even just off-putting can get totally bypassed. Moreover, if our interaction with photography is limited to a ‘Like’ button or the 140-character equivalent, we run the risk of never getting beyond the surface of images and of not developing an understanding of why we like or dislike something. Given the demise of arts criticism in traditional media, this kind of critical thought is arguably more important than ever.

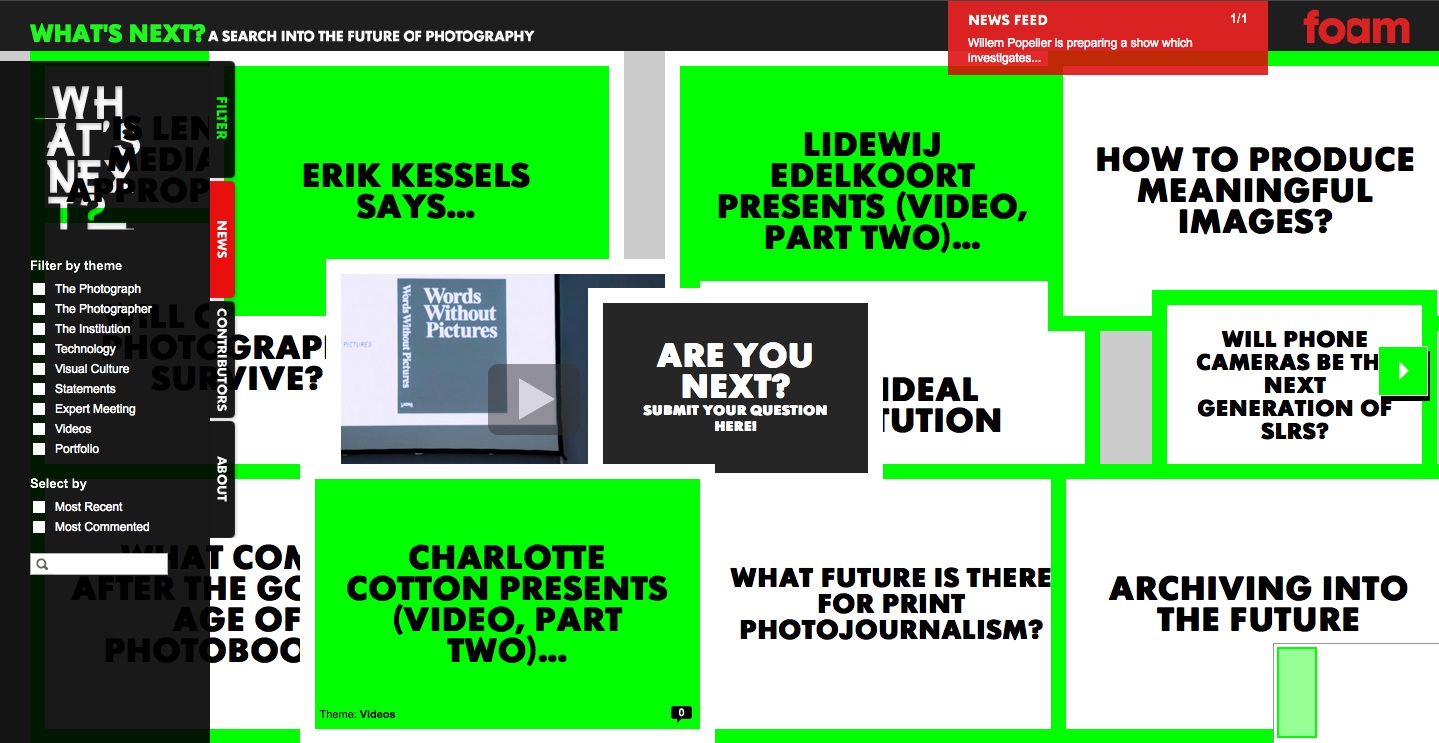

Fortunately there are many online examples that buck the trend. Blogs like Pete Brook’s Prison Photography and Beierle + Keijser’s Mrs Deane are endless sources of hidden gems and considered discussion of current photographic trends. Perhaps the two most encouraging examples are Charlotte Cotton’s 2008 Words Without Pictures and more recently, Foam’s What’s Next?, both vital spaces which use the participatory nature of the net for considered thought and conversation on what is happening in photography today and where this might be leading.

Some might argue that an overly analytical discussion of photographs can get in the way of images. But without a critical discussion, what is going to lead photography to evolve and move forward?