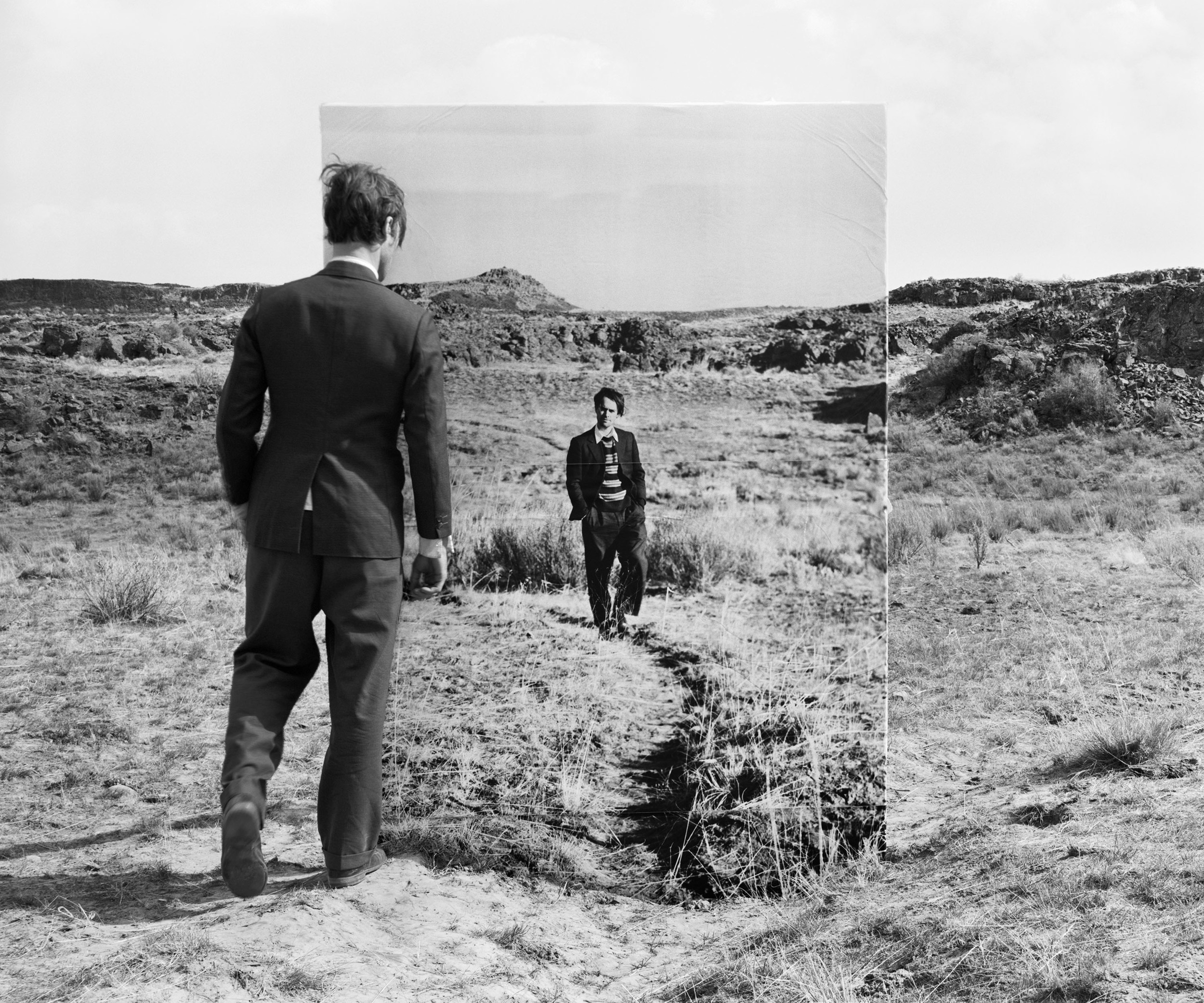

Chris Engman's series Landscapes is based on the vast open spaces of Washington State outside of Seattle, where Engman lives. The title of the series, just like the images themselves, suggests one thing, while revealing many others. He has a show on at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle until Christmas Eve 2010. This interview with Engman was done for the Talent Issue (#24) of Foam magazine which came out in September 2010.

Chris Engman's series Landscapes is based on the vast open spaces of Washington State outside of Seattle, where Engman lives. The title of the series, just like the images themselves, suggests one thing, while revealing many others. He has a show on at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle until Christmas Eve 2010. This interview with Engman was done for the Talent Issue (#24) of Foam magazine which came out in September 2010.

Marc Feustel: What attracted you to the landscapes of eastern Washington that you use for your photographs?

Chris Engman: When I set out to make a photograph I begin with an idea. I write about it, turn it over in my mind, and gradually the requirements for a site take shape. I then go out and drive, sometimes for a long time, until I find that site. The idea is not a response to the landscape; in my work the landscape is a response to the idea. Once I’ve found and used a site I become attached to it, and there are some that I frequently revisit. They go from being spaces where I am free to let my imagination wander to being places with a personal history and familiarity. I have dreams about buying up all that land and doing nothing with it so that it will be left alone.

MF: You refer to these landscapes as resembling ‘an unformed dream or empty canvas waiting to be acted upon.’ What made you want to intervene in these landscapes?

CE: They fulfilled the requirements for the illustration of my ideas. When I refer to these spaces as an empty canvas I mean that they are relatively free from distracting associations, so that the work can just be the work. Undeveloped land, ocean views, deserts, the associations they have are ones that are appropriate to the work: freedom, possibility and a desire for purity.

MF: The Japanese photographer Naoya Hatakeyama has suggested that ‘nature is already so distant from us that you might say it has become a fantasy’. Is this an idea that resonates with you?

CE: I don’t personally feel more distant from nature than I want to be. My work affords me a lot of opportunities to be in nature and for adventure and misadventure. Being and working in extreme places connects me to nature by confirming the power it has over me. I don’t really imagine that there is such a strict division between man and nature. We are a part of nature, when we harm it we harm ourselves.

MF: Can you describe how you go about constructing your images? The process seems quite elaborate.

CE: Every image presents unique challenges. In the case of Equivalence, to begin with I found a suitable piece of private land and got permission to use it. I built a frame and photographed it. Back in Seattle I made fifteen large prints altogether measuring 4.5 meters wide and over 3.5 meters high. The prints had to be skewed digitally to account for the fact that the frame was not parallel to the film plane. I returned to eastern Washington and placed the prints back onto the same frame. In the final photograph you wouldn’t know by looking at it that the prints were ever skewed be cause the camera, replaced to its original location, skews them again back into ‘correct’ perspective. The piece is titled after the series of clouds by Alfred Stieglitz, in which he suggests that his images of clouds can represent inner states and emotions. My version asserts that photographs are not objective and can only ever tell partial truths, and beauty and emotion are constructs of the mind. For me this doesn’t lessen photography, beauty or emotion but makes them all the more interesting.

MF: Manipulation in photography is not new, but digital technology has extended the range of possibilities and the line between straight and manipulated photographs is increasingly blurry. Do you think people’s perceptions of what a photograph is are changing as a result?

CE: One question I get a lot is are they manipulated? The answer is supposed to be no, they are ‘real.’ This is a false dichotomy. All forms of representation are manipulation. But the question gets asked, and at the root of it is a desire for authenticity. What needs to be better understood is that sometimes even heavily manipulated images are truthful and sometimes straight photographs tell lies, so there should be a different set of criteria for authenticity. My own photographs are in many ways closer to what is meant by straight than not. That is, the majority of the digital manipulation that I do could have, at least theoretically, been done in a darkroom. However, I have no qualms about crossing that line when necessary. In The Haul, for example, street signs and text on the buildings have been removed so that the place would have a more generic quality. One thing I will not do is pretend I did something that I did not do. Many photographers are finding ways to make their work be less work, while I have gone in the opposite direction. My photographs are laboured, and they don’t take short cuts. In that sense I am like a sculptor or installation artist who uses photography as a tool.

MF: I am curious to know about your influences and in particular your relationship to landscape photography. Your work occupies quite a unique space and it seems to integrate many different photographic and artistic traditions.

CE: I think a lot about Robert Smithson’s work relating to time and place. The Earthworks artists often have more in common with my process and practice than do landscape photographers. I enjoy the work of Michael Heizer and Walter De Maria, Georges Rousse and Robert Irwin. The re-photographic work of Mark Klett has been an influence recently. Fiction by writers such as Milan Kundera, Salman Rushdie, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Faulkner and Hemingway often directly spurs ideas for particular photographs. Also the writings of the neurologist Oliver Sacks are an influence.

MF: As opposed to many contemporary landscape photographers your photographs don’t seem to have a direct message about the relationship between man and nature. Do you consider that there is a political aspect to your work?

CE: I am a political person but my work is not directly political. A lot of contemporary landscape photography is concerned with human exploitation of the landscape, usually with a pessimistic or nostalgic undertone. Although I am of course concerned about exploitation, the subject of my work concerns abstract ideas relating to perception and the human condition. On the other hand a few of my works do contain some subtle social criticism. One way to read The Haul, for example, is as a questioning of consumerism and the ideas about success that drive us to always want more and do more and never be content. The piece expresses a desire to travel through life with a lighter load.

MF: What are you working on at the moment?

CE: The piece I’m working on is a diptych called Dust to Dust. My plan is to find or make a large pile of sand or dirt and photograph it. For the second part of the diptych I will employ land-moving equipment to rotate the pile ninety degrees clockwise. The mountain of dirt will be reformed in its original shape, the shadows will be repeated with careful timing and camera placement. In this way the pile of dirt will appear to remain stationary while the landscape itself will appear to have moved. The piece is a meditation on impermanence and the fact that not only existence but even the features of the physical world are temporal and will come to an end.