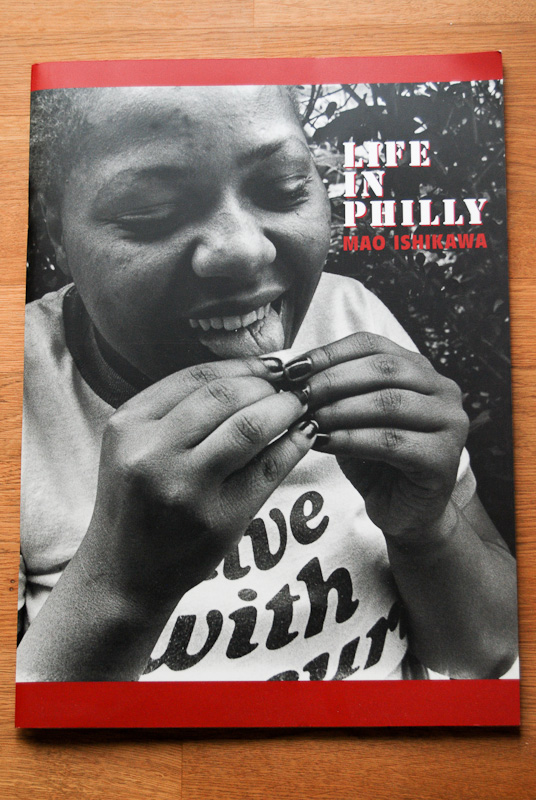

There is a famous saying in Japan, "The nail that sticks out is hammered down." If there is any truth to that over-used trope, Mao Ishikawa cannot have had an easy life. Born in 1953 in Okinawa, she was one of the very few female photographers of her generation who attempted to make a career in a totally male-dominated world. As Okinawa became the most important location for US military bases in Japan, Ishikawa would have grown up surrounded by US soldiers. It is through her relationship with them that her series, Life in Philly, came about.

There is a famous saying in Japan, "The nail that sticks out is hammered down." If there is any truth to that over-used trope, Mao Ishikawa cannot have had an easy life. Born in 1953 in Okinawa, she was one of the very few female photographers of her generation who attempted to make a career in a totally male-dominated world. As Okinawa became the most important location for US military bases in Japan, Ishikawa would have grown up surrounded by US soldiers. It is through her relationship with them that her series, Life in Philly, came about.

In his essay on Ishikawa, Shomei Tomatsu writes that she "lives on the polar opposite of the illusion of objectivity." I think what Tomatsu is getting at is the personal commitment that is evident in Ishikawa's photographs. Her images aren't seeking to document some detached, objective truth about the world around her, instead they are Ishikawa's way of committing herself to the world that she has decided to photograph. This commitment led to Ishikawa becoming one of the Kin-Town women (the women that "befriend" soldiers at the US military base in Kin-Town, Okinawa) that she had decided to photograph.

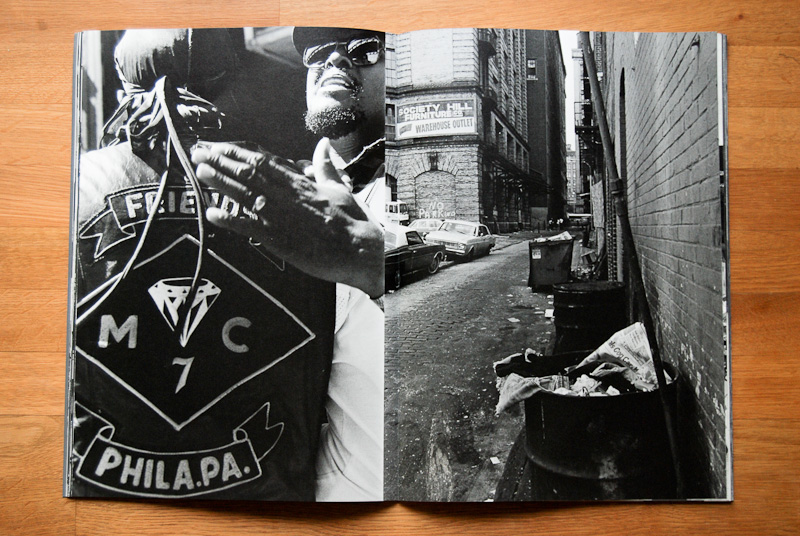

Her involvement in this world eventually led Ishikawa to leave her six-year old daughter with her parents to visit Myron Carr, a US soldier that she met in Okinawa in 1975, in his hometown of Philadelphia. The book brings together a group of 132 of the pictures that Ishikawa took when staying with Carr in Philadelphia over 2 months in 1986. These pictures show the black neighbourhood where Ishikawa spent her time in Philly: corners, stoops, alleys, strip-clubs and the inside of her friends' homes. Many of Ishikawa's subjects are clearly aware of the camera; these aren't images snatched surreptitiously, they create a sense of involvement in the world that they portray.

The most extraordinary thing about these pictures is just how natural they feel. Everything seems to suggest that these are the photographs of an insider, someone who knows these neighbourhoods, and it is hard to believe that they were taken by a Japanese woman who, I presume, had never been to America before. The people that she photographed in the streets of Philly don't appear guarded, indeed they often play up to the camera and on occasion, seem to have totally forgot about the photographer's presence. Ishikawa clearly managed to attain a level of intimacy with her subjects that is difficult to reach. Only the odd image reminds us of Ishikawa's origins with an image that is reminiscent of Tomatsu or Moriyama.

The central section of the book focuses on sex, between Myron Carr's twin brother Byron and his girlfriend. These images are perhaps the most surprisingly natural of all. There is nothing glamourized, romanticized or exaggerated here: this is sex at it's most raw, funny and honest, a brief moment of pleasure that ends up with the couple zoning out in front of the TV drinking a beer and smoking a cigarette.

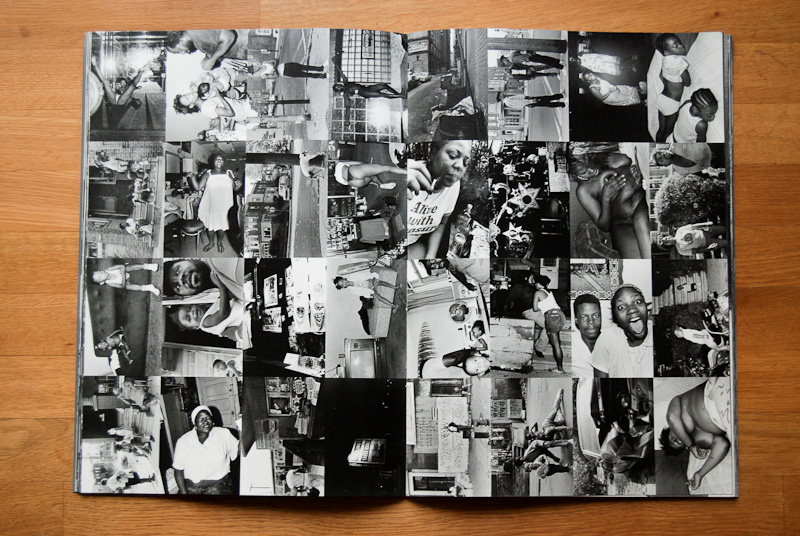

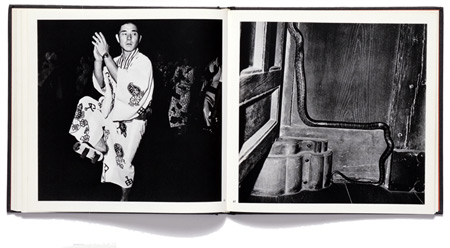

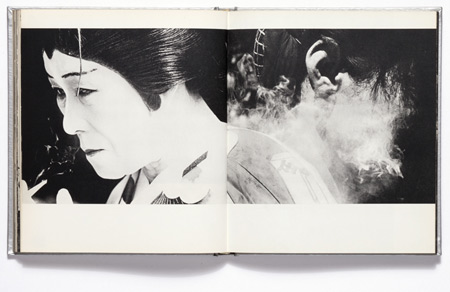

This large-format book presents the pictures in full-bleed that is typical of Japanese 'street photography' and which really contributes to their impact and to drawing you into the pictures. There are a few 'mosaic' spreads (like the one above) in the book mixing vertical and horizontal images, which I'm not sure about: they feel a bit like an attempt to squeeze too many pictures in. I'm also not a big fan of the fonts and the text layout, but the printing and photo-layout don't disappoint and, as this is the first time that this truly unique series has been published, this is one that is definitely worth tracking down.

Mao Ishikawa, Life in Philly, Tokyo: Gallery Out of Place, 64 pages, 25.5 x 36 cm, edition of 1,000, duotone B/W offset, staple-bound. You can order copies here.

Rating: Recommended