Last night was the opening of the Michael Kenna retrospective at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (National Library). The show includes 210 prints of work spanning from the early 1980s until today, 100 of which Kenna is donating to the BNF after the exhibition. I was surprised that he has over 30 years of work behind him and curious to see what a large retrospective show such as this one would say about the development of this artist.

Last night was the opening of the Michael Kenna retrospective at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (National Library). The show includes 210 prints of work spanning from the early 1980s until today, 100 of which Kenna is donating to the BNF after the exhibition. I was surprised that he has over 30 years of work behind him and curious to see what a large retrospective show such as this one would say about the development of this artist.

The first thing to mention is the printing. It is clear from the way that he signs and editions his prints that Kenna is nothing if not meticulous and his small, square format prints are quite stunning. When he moved to the US in the late 1970s, Kenna became Ruth Bernhard's assistant and printer, and clearly became very good at his job.

The exhibition is well laid out and the BNF's production values are always high. The work is grouped into a series of themes, from 'The Tree' to 'The Far East' with a healthy dose of 'Melancholy'. The show includes a large amount of work from England and the United States (his native and adopted homes), but also a significant amount of recent work shot all over the world (Dubai, New York, Hong Kong, China, and Kenna's beloved Japan).

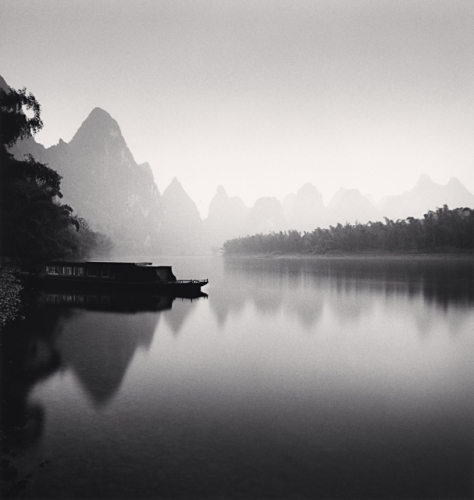

Kenna's surgically-precise minimalist compositions, which—in his own words—are akin to haiku poems, have remained remarkably consistent over time. He is driven by a desire for pure images where not a single element is left to chance. This compositional rigour is paired with long exposures taken overnight or at dawn or dusk, playing with both texture and light in order to create a very personal dream-like vision of the world. Kenna is masterful in his control of all of these elements and this has enabled him to develop an incredibly consistent personal vision.

However, despite all of this virtuosity, I ended up feeling frustratingly indifferent. One of the wall texts in the show claims that Kenna privileges suggestion over description, but I think he goes far beyond suggestion. His personal vision is so strong that his landscapes tend to resemble each other, whether they are taken in Bognor Regis (below) or in Hokkaido.

Kenna's idealised vision of the world seems to iron out the details and imperfections which give each landscape its distinctiveness. There are moments when his eye seems to become more daring, even critical (see the above Dubai skyline), but these are few and far between. Kenna has increasingly ventured into cities with his camera with mixed results. Particularly in cities with iconic monuments or architecture, I found that his imagery comes dangerously close to upmarket postcard territory (his Brooklyn Bridge images for a good example of this).

In some ways Kenna's approach seems to be more painterly than photographic: instead of accepting the camera's all-seeing-eye that reveals everything which appears in the frame, you get the sense that Kenna uses the camera to recreate his interior vision of the world.

Finally, I think that the size of this exhibition is problematic. It is very difficult to compile 210 photographic haikus without suffocating the space that each one of these needs. Instead of the images combining into some form of symphony, I found that repetition sets in about halfway through.

In one of the final wall texts, reference is made to Barthes statement "All of a sudden, I became indifferent to the fact of not being modern." This seems appropriate for Kenna. He is in search of a particular kind of beauty and is not concerned with the now: none of his images seem to have any link to the time in which they were made. If you can accept this about him, this exhibition has a better chance of resonating with you.

Michael Kenna Bibliothèque nationale de France, Site Richelieu. 13 October 2009 - 24 January 2010.

Rating: Worth a look