I spend quite a bit of time with photobooks, whether it be for this blog, it's slightly less wordy Tumblr cousin, or just for my personal pleasure, but it is not often that I get to spend a day with a book like this one. In fact, it is not a book but a maquette for a book that was never published. Entitled Mario, it is a children's photobook by Cornell Capa that tells the story of a young Peruvian boy named Mario. I'm not sure why it was never published but I understand that this maquette spent most of it's life sitting on a shelf and that it has only recently resurfaced. So when I was given the opportunity to borrow the book for a day, I jumped at the opportunity.

Cornell Capa is probably best known for founding the International Center of Photography in New York in 1974 and perhaps also for being Robert Capa's younger brother, but he was also a photographer and a member of Magnum Photos in his own right. His approach to photography was articulated in his 1968 book, The Concerned Photographer, which he described as a book of "images in which genuine human feeling predominates over commercial cynicism or disinterested formalism". Mario is very much in line with this philosophy.

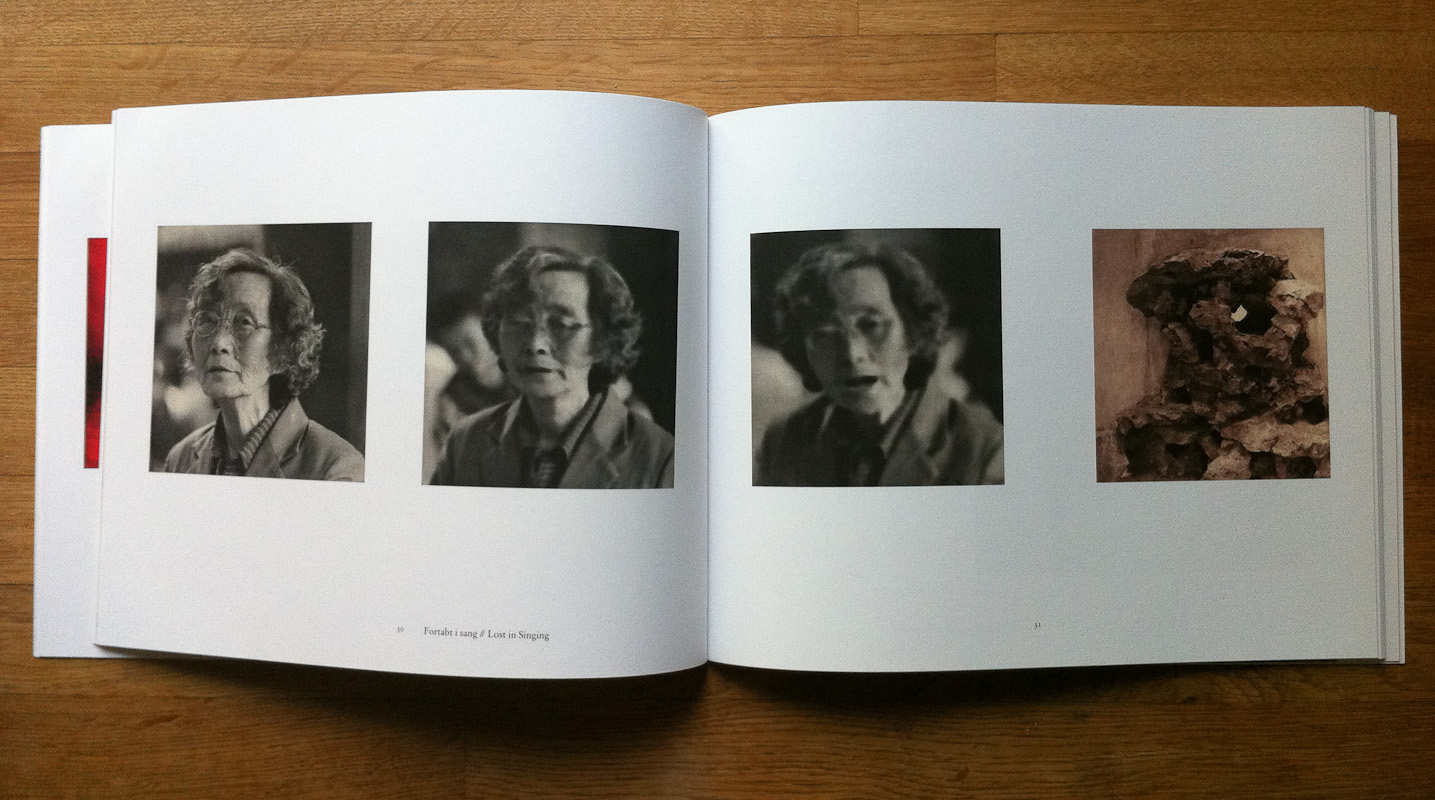

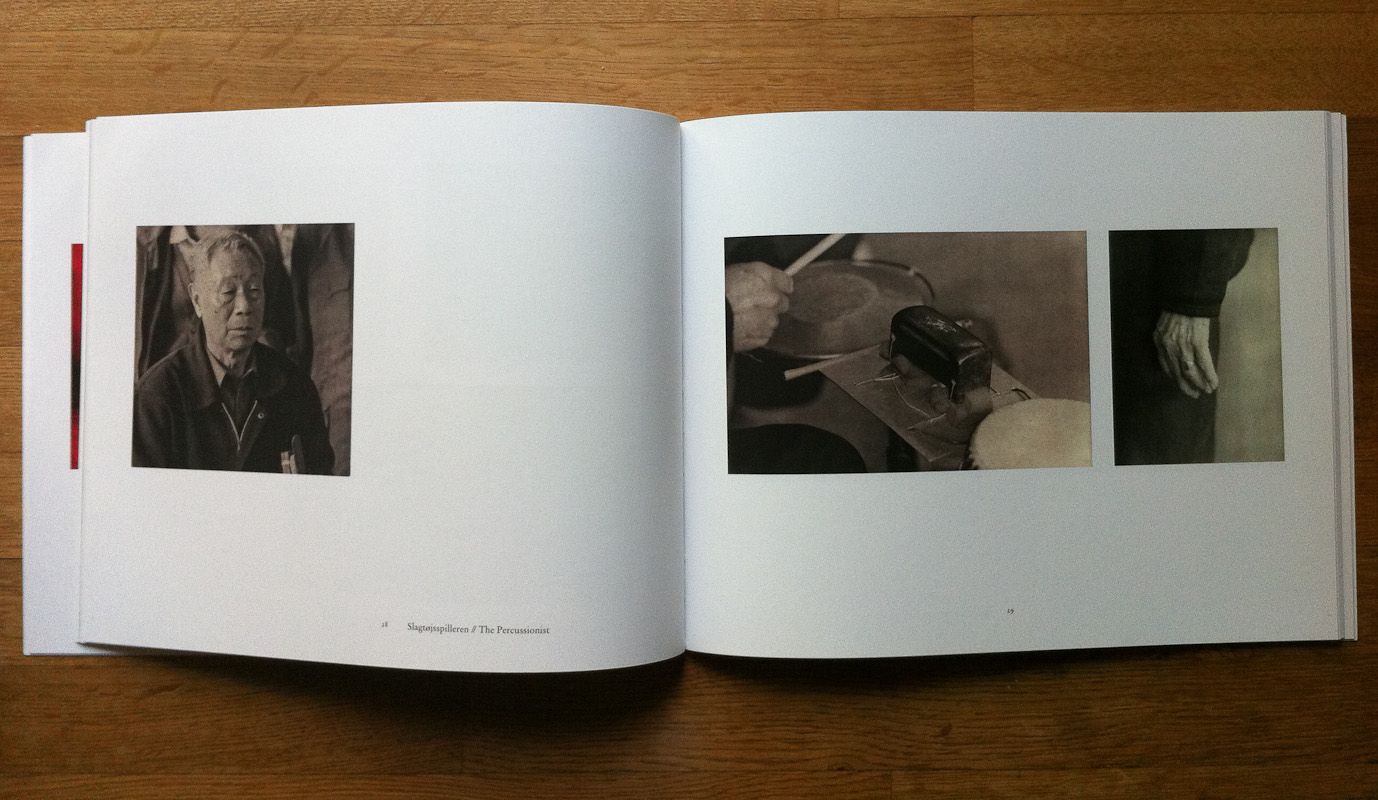

The book is made up of approximately 60 images by Cornell Capa. The photographs are predominantly black-and-white although it also includes a handful of colour images. The photographs are accompanied by a narrative written by Sam Holmes which follows a Quechuan Indian boy named Mario who dreams of going to America where he will buy a tractor for his father. The story follows Mario from his family's simple life on the farm to his school and then on to the city of Cuzco in southeastern Peru for the Corpus Christi Festival, ending with Mario returning home. When in Cuzco, Mario happens to meet an American boy who is about the same age as him, his first encounter with the country he has been dreaming of visiting.

Although the text is clearly aimed at children, there are also some quite dense historical passages. One section deals with the richness of the ancient Inca civilization while another describes the rituals of the Corpus Christi festival. One of the most fascinating things about Mario, is that beneath the childlike language, the book has a strong political message. Returning home after his encounter with the young American during which he experiences some of the comforts of the Western consumerist lifestyle after sleeping over with his family in a hotel in Cuzco, Mario grows to appreciate the simple, ancient beauty and traditions of the rural land where he is from and his urge to travel to the city or to America fades. Today's right-wing American cable news networks would be outraged by the book's progressive, 'socialist' message.

I'm not sure exactly when the maquette for Mario was made (my guess would be in the late 1950s or 1960s), but it is an extremely interesting window onto American politics at the time and to the forthcoming interventionist American foreign policy of the 1970s. Although it is aimed at children, the book is essentially a progressive political tract... you could even go so far as to call it political propaganda.

The maquette is an interesting insight into the photobook-making process of the pre-digital era. The design is done by using a set of prints made specifically for the layout which are then stuck into the pages of the dummy book. The text is laid out in the same fashion. The design is pretty dynamic: the book doesn't follow a 'one-page-per-picture' format but plays with different formats and layouts for the images. Having spent most of its life on a shelf, the prints are in excellent condition, even those in colour. As an added bonus, I have featured more images of Mario than usual as this is not a book that you are likely to be able to get your hands on.

What makes this maquette particularly exciting is that I believe that, aside from the odd exhibition catalogue, Capa did not publish any photobooks of his work. With Horacio Fernandez's The Latin American Photobook coming out next week and Parr & Badger's The Photobook: A History Vol. 3 — with a chapter devoted to 'propaganda' — currently in the making, Mario is a timely (re)discovery.