The Twisted Movements of a Gigantic Creature

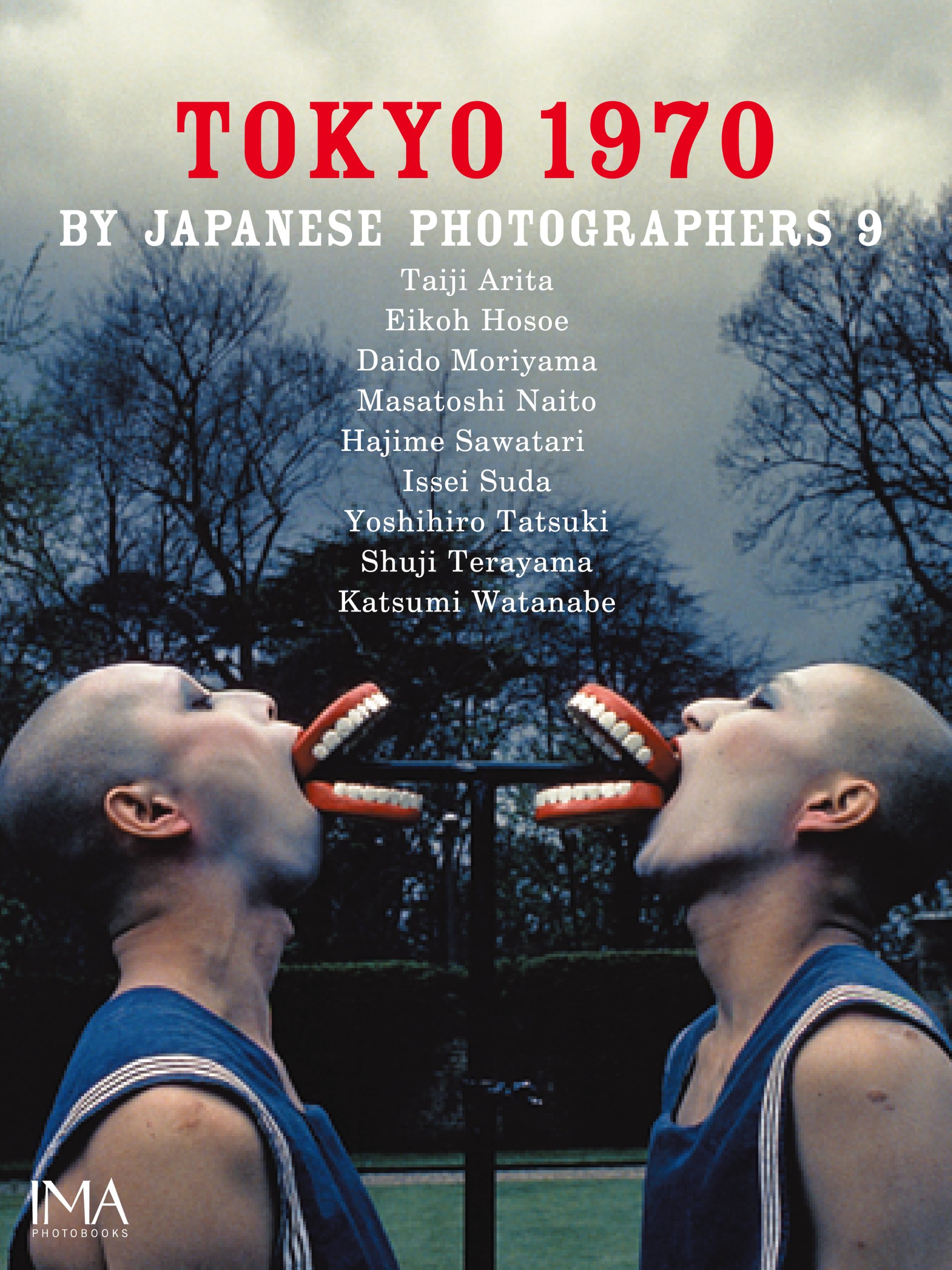

Tokyo 1970 by Japanese Photographers 9 (Tokyo: Amana, 2013)

"The Twisted Movements of a Gigantic Creature" is an essay written for the exhibition catalogue to Tokyo 1970 by Japanese Photographers 9.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a period of extraordinary turbulence and transformation in Japan. The hardship of the immediate postwar years had given way to rapid economic growth and technological innovation that not only transformed the economy but also led to profound changes in the country’s social, political and urban structure. While these changes thrust the nation towards the future, the speed at which they were taking place also led to a great sense of uncertainty and instability. Naturally, this state of affairs also impacted profoundly on the arts, and the period saw a cultural renaissance that spread across literature, film, theatre, performance art and photography. What characterized this explosion of artistic activity was a desire to break with the past and to find new artistic languages to deal with the radically new face of Japan that was emerging.

In parallel to the social changes that had been taking place since the end of the war, Japanese photography had also been undergoing a metamorphosis over the previous two decades. The social realism of the 1950s championed by Ken Domon had given way to a more expressive subjective documentary style represented by the photographers that had founded the Vivo group (Eikoh Hosoe, Kikuji Kawada, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, Akira Tanno, and Shomei Tomatsu) in 1957. They advocated a break from the strict objectivity of the past in favour of a highly expressive documentary style where the author would be profoundly engaged with the subject.

Less than a decade later, the changes that were taking place convinced a new generation of photographers to once again seek to break with the past. Whereas the Vivo photographers seemed to be addressing the question of the identity of the Japanese nation in the face of the Americanization of the postwar years, by the late 1960s this question had evolved. The focus was no longer on the nation or the collective but on the place of the individual within society: rather than “What is Japan?” the question was becoming “Where do we fit in this new Japan?” Nowhere was this more keenly felt than in Tokyo: the capital acted as a lightning rod for the transformations of the times and their turbulent consequences.

Whether directly or indirectly, Tokyo became the central character in the photography of the time. The photographers presented here all approach the city in different ways: from the visual chaos of the city that is reflected in Moriyama’s work, to Naito’s vision of Tokyo’s dark underbelly, or from Watanabe’s creatures of the the Shinjuku night to Suda’s melancholy vision of a timeless face of the city, Tokyo plays a central role in all of these images.

Issei Suda, Waga Tokyo 100

By 1968 student movements were forming around the world to protest against the rapid expansion of capitalism. In Japan, these movements combined with protests against the opening of a new Narita airport and opposition to the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty to create a particularly explosive cocktail of dissent. A small group of artists came together to harness the energy of this time to produce a magazine that pushed photography in a radical new direction. Founded by the critic Koji Taki, editor and photographer Takuma Nakahira, photographer Yutaka Takanashi and poet and critic Takahiko Okada, (the fifth member, the photographer Daido Moriyama, did not join until the second issue), in its first issue Provoke laid out its aims with a brash and hugely ambitious manifesto:

“Visual images are not ideological themselves. They cannot represent the totality of an idea, nor are they interchangeable like words. However, their irreversible materiality—reality cut out by the camera—belongs to the reverse side of the world of language. Photographic images, therefore, often unexpectedly stimulate language and ideas. Thus petrified language can transcend itself and become an idea, resulting in a new language and new ideas.

Today, when words have lost their material base—in other words, their reality—and seem suspended midair, a photographer’s eye can capture fragments of reality that cannot be expressed in language as it is. He can submit those images as documents to be considered alongside language and ideology. This is why, brash as it may seem, Provoke has the subtitle ‘provocative documents for the pursuit of ideas’”.

For the members of Provoke, the language of photography was no longer capable of dealing with the new world that was rising up around them. They decided to throw the photographic rulebook out the window, to make a decisive break with the past and attempt to develop an entirely new photographic language. The style of the group became referred to as are, bure, boke (rough, blurred, out of focus) in reference to the deliberately rough aesthetic of their black and white images. But more than this visual style, which was also used by other photographers, what defined Provoke was the radical nature of their artistic statement: they were determined to push photography to its limits.

While the magazine itself was short-lived—the first issue came out in November 1968 and the group came to an end in 1970 with the book, Mazu tashikarashisa no sekai o sutero: shashin to gengo no shiso (First, Abandon the World of Pseudo-Certainty)—the members of Provoke continued to develop the ideas that they had first laid out in the magazine. Perhaps the most extreme and radical statement by any of the Provoke photographers came just two years later from the last member to have joined the group, Daido Moriyama. Moriyama’s book Shashin yo sayonara (Bye, Bye Photography) is one of the most extreme bodies of work to have been produced during this period, or indeed any period in photography’s history. With this book, Moriyama stated his intention clearly, “I wanted to go to the end of photography.” Rather than building a new language, Moriyama seemed to be determined to tear the existing photographic vocabulary apart. The book pushes photography to the point of legibility: its images are so rough, scratched, grainy, distorted that it is often difficult to make out the subjects of these photographs. In addition to his own images, Moriyama also integrated found images and snapshots of TV screens, emphasizing his distrust of the link between image and reality and echoing the visual chaos that was increasingly enveloping the city of Tokyo. Moriyama has gone on to become one of the most prolific photographers of the twentieth century, producing dozens of series and countless publications over the past four decades, but Shashin yo Sayonara remains his most extreme body of work to date.

Although only three issues of Provoke were released (with a print run of 1,000 copies), over time the magazine has become the figurehead for Japanese photography in the West. As the interest and scholarly research in Japanese photography has increased in recent years and as the photobook’s importance in the development of the medium of the photography has been gaining recognition, many Westerners have been drawn to Japanese photography through its extraordinary publications. The raw power of Provoke (and its rarity) have contributed to its legend, however, it is important not to overstate its importance. Given its very limited print run and short lifespan, the magazine was only seen by a handful of insiders at the time. In addition its radical position was by no means broadly representative of the new generation of photographers emerging in Japan. As the diversity of the works in this collection shows, there were many different photographic approaches that emerged to change the face of Japanese photography in the late 1960s and 1970s. Although their images differ greatly in style and tone, what the photographers in this exhibition share is a willingness to break with the photography of the past and a common fascination with the city of Tokyo. While not all of their methods were as radical as those of the Provoke members, they were united by their aim of developing new photographic approaches.

In fact, just as the founders of Provoke were pushing back against the consumerisation of Japanese society, others began to produce work that openly borrowed from the language of commercial and fashion photography. Hajime Sawatari was a successful commercial photographer at the time, having begun his photographic career at the prestigious Nippon Design Center (NDC). Having left the NDC to become freelance in 1966, from the early 1970s Sawatari began to produce series of personal work that focused on women and the relationship between the photographer and his model. Series like Alice, Nadia and Kinky focus on a single model set in a fantastical world, with images that oscillate between childlike innocence and heady eroticism. Although their style is heavily informed by the fashion photography of the time, these images are freer and more intimate than Sawatari’s commercial work. Kinky is a playful improvisation between the photographer and his model set in a psychedelic world influenced by the music Sawatari was listening to at the time, but it is also a document of his first encounter with Hiroko Arahari, with whom he eventually fell in love and later married. Sawatari’s use of colour for Kinky was a bold statement at a time when the predominant style in art photography was known as konpora, based on the seminal 1966 exhibition at George Eastman House entitled “Contemporary Photographers: Towards a Social Landscape.” The style referred to black and white images (generally in landscape format) focusing on the banality of everyday life and marked by their objectivity and composition that was in complete contrast to the are, bure, boke of Provoke.

Yoshihiro Tatsuki’s series Shitadenshi Tenshi shares the playful and improvised feel of Sawatari’s Kinky images. The series subverts the usual relationship between photographer and model that was prevalent at the time: rather than Tatsuki dictating this “angel”’s poses, he seems to be chasing after her through the city, trying and failing to catch her, as if to mirror photography’s desperate (and hopeless) quest to capture reality itself. In an unprecedented move, the influential editor Shoji Yamagishi devoted a full 56 pages to the series in the April 1965 issue of Camera Mainichi magazine, as part of his aim of supporting young photographers rather than established figures.

Taiji Arita began his photographic career as a student of Yasuhiro Ishimoto at Tokyo Sogo College of Photography. Like Sawatari, Arita then integrated the photography division of the NDC, becoming freelance in 1966. Over the course of thirteen issues of Camera Mainichi magazine in 1973 and 1974, Arita produced a series of images of his first wife Jessica and their son Cohen taken over several years that became known as First Born. Like Sawatari and Tatsuki’s work, these images are clearly the result of a collaboration between the photographer and his ‘model.’ But Arita went much further, mixing elaborately posed and structured images with candid photographs, thereby creating an elaborate performance for the camera. Although they deal with the most intimate of experiences—the birth of a first child—these highly staged images create a deliberately artificial realm that dramatizes the act and removes it from reality. Arita’s wife described the the series as a collaboration which “directly questions our (way of life).” With First Born, Arita and his wife intertwined the birth of their son with the birth of a series of photographs.

Shuji Terayama, Mysterious Guests

Although there was little that brought Sawatari, Tatsuki or Arita’s work close to the radical experimentation of Provoke, there was one artist whose influence was felt throughout the photography world at the time. Shuji Terayama was not primarily a photographer, but a major figure in the world of avant garde theatre. Terayama had contracted nephritis during his university years and strangely it was through this illness that his artistic activity was to take form in the shape of a series of literary salons which he held in his hospital room. Over time he surrounded himself with a troupe of itinerant performers, musicians and artists that eventually coalesced into the Tenjo Sajiki theatre company. Like Provoke, Tenjo Sajiki’s aims were radical, seeking to “revolutionize real life without resorting to politics.” Whereas the photographers of Provoke were questioning photography’s ability to capture reality, Terayama was striving to blend real life inextricably with theatre by taking it out of the theatre hall and into the streets of the city and even into people’s homes. The photographs presented here give a clear sense of the intoxicating, grotesque and carnivalesque world that Terayama created with Tenjo Sajiki, a world that would profoundly influence many of the photographers of the time from Eikoh Hosoe to Masatoshi Naito. In the words of the theatre critic Akihiko Senda, Terayama was “the eternal avant-garde.”

In fact, it was thanks to Terayama that Issei Suda was able to begin his career as a photographer for the Tenjo Sajiki company from 1967 to 1970. This experience was the catalyst for Suda’s most famous series Fushi Kaden, a reflection on the role of tradition and modernity in Japan, for which he travelled across the country photographing its many festivals. Suda’s favourite photographic subject is “everyday life”, which he describes as having “no clearly defined substance.” This idea is palpable in Suda’s Waga Tokyo 100: in these images the city can only be glimpsed through a combination of small details and portraits. The city’s structure and architecture are barely visible, however, over the course of the series a strong atmosphere emerges. Suda was born and raised in the Kanda area of Tokyo, one of the city’s more traditional areas, despite being surrounded by rapidly modernising districts. Perhaps because of this Suda’s Tokyo doesn’t bear the external signs of the modernisation that was transforming the city, in fact its side streets and alleys seem to be those of a small town. His images do not share the drama and exhilaration of Provoke, nor the cool detachment of the konpora photographers. Instead, they are infused with a quiet sense of mystery and a feeling of nostalgia and melancholy for the past.

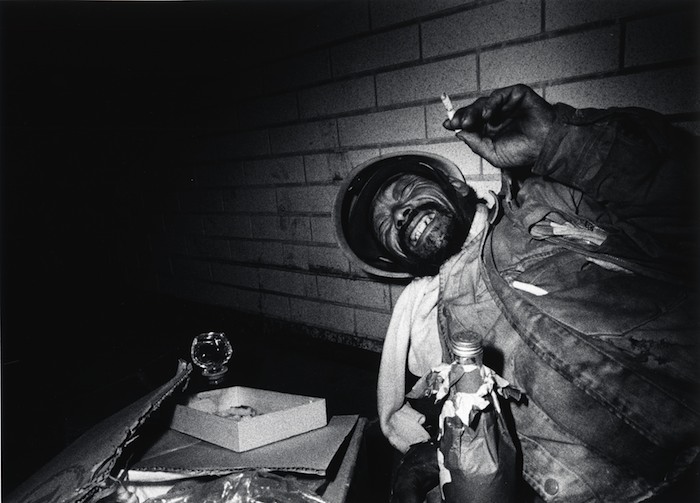

Masatoshi Naito, Tokyo

Like Suda, Masatoshi Naito is perhaps best known for his photographs of Japanese folklore, however his visual universe is altogether darker. His aesthetic shares the hallmarks of the are, bure, boke style associated with Provoke, but Naito did not share their radical thinking on photography and language. In issue 14 of Déjà-vu which was magazine devoted to Provoke, Naito describes this difference in approach, “Provoke was arguing for the centre, I concentrated on the marginal and the rural.” Amidst the transformation of the city, which he compared to “the gnarled, twisted movements of some gigantic creature,” Naito turned away from the surface of the city to those “dark crater-like spots” where “the real psyche of Tokyo is hidden.” His photographs of Tokyo reveal an invisible, subterranean face of the city. His portraits are like apparitions, the harsh light of his flash revealing almost nothing of their surroundings as these characters seem to emerge only briefly from the darkness.

While the city of Tokyo does not have a true centre, if there was one district that was at the heart of the artistic explosion of this period, then it must be Shinjuku. This is where the street photographer Katsumi Watanabe plied his trade. Watanabe first encountered photography as an assistant at the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper in his native Morioka. He moved to Tokyo in 1962, joining the famous Tojo Kaikan portrait studio. It was during this time that he met the street photographer Mr S. who worked in the area of Kabukicho in Shinjuku, a huge nightlife district centred on the sex trade. After cutting his teeth in the entertainment districts of Shinbashi, Shibuya and Ueno, Watanabe obtained Mr S’s blessing to move into Shinjuku. Night after night Watanabe spent in Kabukicho, selling three portraits for 200 yen. His customers were the habitués of the area, the hostesses, barhands, dancers and cross-dressers. Unlike the other works presented here, these portraits were purely commercial. They are not candid, but images in which the subject is playing up to the camera, striking their best pose for a photograph that they could send home or hang in the bar or club where they worked. However, over time, Watanabe accumulated an extraordinary archive of these images that became far more than a collection of commercial portraits but an illustrated history of the characters of Shinjuku during its heyday. Watanabe was fond of saying “All Shinjuku is a stage” and, like Suda was for Terayama’s Tenjo Sajiki group, Watanabe was its photographer.

Of all the photographer’s presented here, Eikoh Hosoe’s work most directly reflects the artistic cross-pollination of the time. He has drawn on literature with his portraits of Yukio Mishima in the series Barakei (Ordeal by Roses), as well as dance and performance with Kamaitachi and The Butterfly Dream, respectively with Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, the two central figures of Butoh dance. Simon: A Private Landscape is a series of photographs made in collaboration with the performance artist Simon Yotsuya in downtown Tokyo. The series acts as a companion piece to Kamaitachi, in which Hosoe and Hijikata recreated their memories of the final months of the war in Yamagata prefecture in Northern Japan through a mix of documentary and performance. Simon extends the visual universe of Kamaitachi to the city, this time dramatizing the photographer’s memories of Tokyo’s shitamachi area before he was evacuated to the countryside. The images share the same hallucinatory quality found in Kamaitachi: Simon Yotsuya appears like a supernatural being only visible to the photographer’s lens as he navigates through the ordinary life of the city.

The period covered in this exhibition was one of the most turbulent, exhilarating, but also traumatic transformations in the city’s history. What unites the work in this exhibition is that these images were all made as a response to a city changing in front of these photographers’ eyes. Looking at these different series there is no clear picture that emerges: instead, they are united by a series of different threads that weave together into a complex web of meaning and dissonance. This web is in the image of the city of Tokyo itself. Even today it does not present a single recognizable face like other major cities such as Paris or New York. Several decades later, Tokyo continues its metamorphosis, never attaining a stable state.

By Marc Feustel