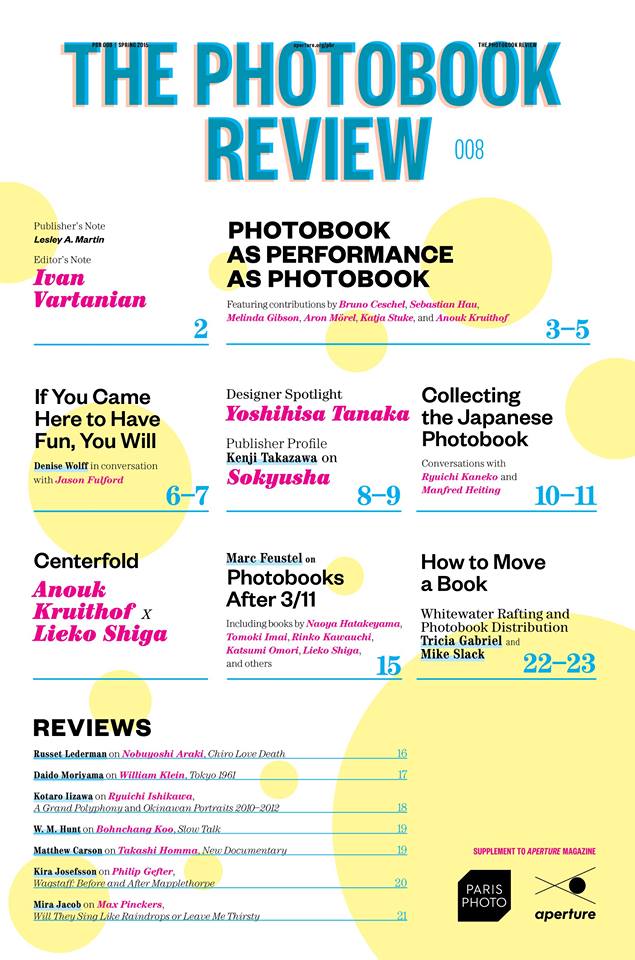

Photobooks After 3/11

The PhotoBook Review, Issue 008, April 2015

It has been four years since the Great Tohoku Earthquake unleashed a series of tsunami waves which struck a vast area of Japan’s northeastern coastline, and caused a severe nuclear incident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Japan is no stranger to natural and man-made disasters. However, since the 1960s the nation has, by and large, experienced peace and prosperity. Since the post-bubble years of the 1990s, much of Japanese contemporary art has been driven by self-representation and aesthetics. But the events of March 11, 2011 (referred to in Japan as 3/11) have profoundly impacted the way art is both made and received in Japan, and today the social and documentary concerns that characterized the postwar years have risen back to the surface.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, photographers from around the country—and indeed the world—flocked to the devastated area. In the following months, book after book was published, seemingly documenting every inch of the devastated coastline. This photographic reaction is both natural and necessary, as if events of this magnitude require images to make it possible for us to begin to comprehend them. However, the sheer volume of these book projects quickly became overwhelming. It was difficult to feel anything but numb when faced with these endless images of devastated landscapes.

It was in this context that projects began to emerge with new approaches to this difficult subject. As early as April 2011, Rinko Kawauchi traveled to the earthquake-devastated towns of Ishinomaki, Onagawa, Kesennuma, and Rikuzentakata. From this journey she created the series Light and Shadow, based on her encounter with a pair of pigeons, one black, one white. This became the project’s theme: the dualism of light and shadow, good and evil. While the photographs depict destruction, Kawauchi’s work does not feel like a document, but rather a transcendence of the disaster where despair already contains the seeds of hope. Two publications have emerged from the series, both titled Light and Shadow: a short, self-published book in 2012, and an expanded edit of the series published by SUPER LABO in 2014.

Katsumi Omori, Subete wa hajimete okoru

New approaches were also at work in two projects dealing with the Fukushima nuclear incident that resulted from the earthquake: Katsumi Omori’s Subete wa hajimete okoru (Everything happens for the first time, Match and Company, 2011) and Takashi Homma’s Sono mori no kodomo (Mushrooms from the forest, Blind Gallery, 2011), both of which were reviewed by Ivan Vartanian in The PhotoBook Review 002. Fukushima is the least likely of photographic subjects as it demands the impossible: to photograph radiation—the invisible. Omori described the compulsion that drove him to Fukushima: “I must go to Fukushima. I must shoot the radiation (though it cannot be shot).” By employing a halation effect throughout his series, he lays bare the limitations of photography in the face of this invisible threat, while also giving that threat a form.

At first glance, Homma’s images of forests and wild mushrooms seem to bear no relation to the nuclear power plant, but their meaning is transformed by a brief text buried at the end of the book. In it, Homma explains that mushrooms absorb radiation faster than other living organisms; those he collected in the forests of Fukushima Prefecture contain much higher levels of radiation than elsewhere in Japan. The experience is unsettling, forcing the viewer back through the images with a very different eye. Tomoki Imai’s Semicircle Law (Match and Company, 2013) uses a similar device. His seemingly anodyne forest landscapes are transformed by a diagram at the end of the book revealing that his photographs were taken on either side of the twenty-kilometer security radius established by the Japanese government around the stricken nuclear plant. Imai himself has said that he thinks these images’ significance will depend on which vantage point the future will bring.

Non-Japanese artists have also been drawn to the affected region. The German photographer Hans-Christian Schink traveled to Japan one year after the quake to photograph the coastline. Tohoku (Hatje Cantz, 2013) provides a complex view of the aftermath of 3/11, in which the tsunami’s impact ranges from the imperceptible to the brutal—a landscape still caught in the midst of a long healing process. More recently, Antoine D’Agata produced a surprising new book on Fukushima. Over the course of six hundred black-and-white plates, Fukushima (SUPER LABO, 2014) presents a typology of those houses abandoned due to their proximity to the stricken nuclear plant. A far cry from D’Agata’s signature work, the uncharacteristic coolness of these images builds to a foreboding sense of silence and emptiness.

While all the projects mentioned above were created by photographers from outside the Tohoku region, for some the events of 3/11 were of a more personal nature. Iwate-born Kazuma Obara’s Reset Beyond Fukushima (Lars Müller, 2012) goes beyond a documentation of the catastrophe to become a call to action—the book’s subtitle is Will the Nuclear Catastrophe Bring Humanity to Its Senses?—in the grand tradition of the Japanese protest book. Naoya Hatakeyama is also from Iwate, and his book Kesengawa (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2012; Editions Light Motiv, 2013) is concerned with the destruction of his hometown of Rikuzentakata. Kesengawa has two distinct halves. The first contains photographs that Hatakeyama had been casually producing over the years along the Kesen River, which runs through his hometown of Rikuzentakata. The book then shifts into the photographs taken in his hometown in the aftermath of the wave. In the book’s afterword he describes his aim to “bring the event closer to people, to compress the physical distance.” Whereas Homma and Imai’s images are altered by the text that follows them, in the case of Kesengawa, the photographs are transformed by the events themselves. Snapshots made only to be tucked away in a small box in his studio suddenly gained great significance—a profound illustration of the ever-shifting relationship between photography and the world.

Lieko Shiga was directly affected by the tsunami. In 2008 the young artist had relocated to the small coastal village of Kitakama in Miyagi prefecture, where she had been given a home and a studio in exchange for taking on the role of official photographer for this small community. Shiga had been working on an ambitious project about her adoptive home when the tsunami struck, destroying much of the community and her studio with it. She went on to finish the project, which became a book and an exhibition. Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Beach, Akaaka, 2013) is not a book about the tsunami, but one whose course was profoundly affected by it. Like many of the projects referred to here, Rasen Kaigan is also concerned with bringing the invisible to light: rather than documenting the surface of her adoptive community, Shiga chose to focus on its fantasies, dreams, and memories—its “essence.”

Of all the books that deal with the 3/11 tsunami, Tsunami, Photographs, and Then: Lost and Found Project (Akaaka, 2014) is perhaps that which says the most about photography’s importance at times like these. The book provides an overview of the work of the Lost and Found Project, a group that was formed in order to attempt to retrieve photographs that had been scattered by the wave, preserve them, and attempt to return them to their owners. Initiatives like this one sprung up all along the Tohoku coast, and are a testament to the vital importance accorded to photographs when all has been lost.

An extraordinary breadth of projects and approaches have emerged around 3/11 in the past four years. The books mentioned here all deal with the subject directly, but there are countless others in which these disasters are a powerful, if indirect, undercurrent; the many projects referred to in this piece only represent a beginning. Looking to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, these events remained key themes for decades after the events. Arguably the two most powerful bodies of work on the atomic bombings, Kikuji Kawada’s Chizu (The Map, 1965) and Shomei Tomatsu’s 11:02 Nagasaki (1966), were not published until twenty years after the fact. Today, the resurgence of social concerns echoes the artistic engagement of those postwar years. Perhaps the greatest photobooks to deal with 3/11 are still to come.

By Marc Feustel