Interview with Toshio Shibata

Some/Things #4, "The Wings of a Locust," March 2011

You studied painting and print-making before you became a photographer. Can you tell me how you came to adopt photography as your medium and how your studies affected your approach to taking photographs?

At university, in 1968, I was studying painting. I was learning very classic things: charcoal drawings, oil paintings. During that year with the political upheaval in Japan everything was changing. Because of the student riots they shut down my university and there were no classes. This made me think that it was time to try something new. I came across the work of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol who were making silkscreen prints using photographic images, which I was very attracted to. What attracted me initially was the simplicity and directness of this process compared to the difficulty of painting exact figurative images. Many art forms require you to practice constantly in order to be able to make a simple figurative image. With photography, if you want a picture of a particular thing, you just have to take it. So my first experiences in photography involved making silkscreen prints using photographic images. I am very interested in print-making and I tried many different processes...woodcuts, copper etchings.

What were some of the other works of art that influenced you at that time?

During my last year of postgraduate school in the summer of 1974 I decided to travel through the United States to see the reality of American contemporary art for myself. I remember having mixed feelings from this trip, powerful emotions but that were tinged with a little disappointment. After this trip, I became interested in super-realism and minimalism. I was so attracted to the image itself and I had come to feel that just to draw well was essentially boring. I was also attracted to the new American cinema of that time, as well as photographic images. The Last Picture Show by Peter Bogdanovich was one of my favorite movies. After ten months working for a film company in Japan, I went to Belgium where I had some friends, to study more about fine art, but in truth I just wanted to see more of the world.

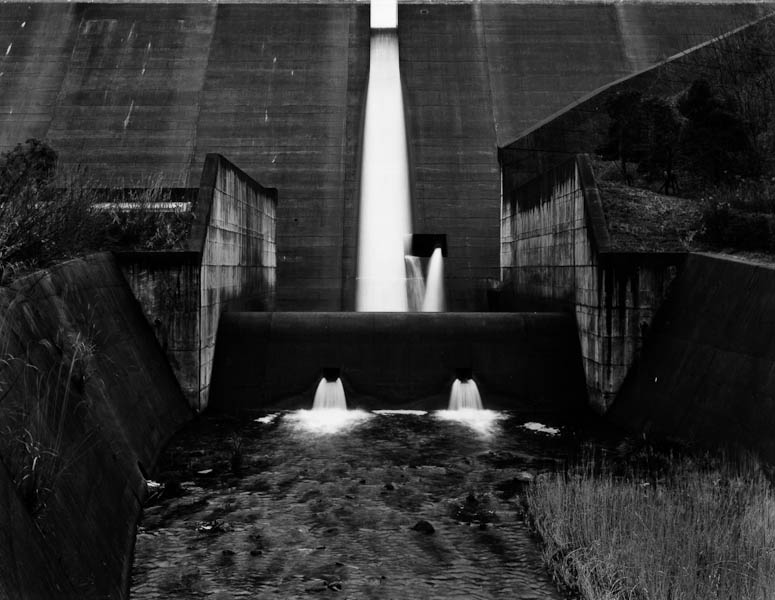

Shuto Town, Yamaguchi Prefecture, 2002

You studied at the Royal Academy of Art in Ghent. Did this European artistic education have a big influence on your approach as a photographer?

After finishing university in Japan and working for one year, I got a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Ghent in Belgium. When I arrived at the art school the director suggested that I study photography given my previous studies of oil painting and print- making. While I was in Ghent, I made a trip to Paris where I visited the Zabriskie Gallery, just in front of the Pompidou Center. At the time there was a show on called The American West: One Hundred Years of Landscape Photography (1978) which included work by the Group f/64 artists like Ansel Adams and other West Coast artists.

I already had the sense that I wanted to work with photography but at the time in the 1970s the Japanese photographic scene was very different to my sensibilities. It was based around social protest with photographers like Daido Moriyama. After seeing the American West show, I felt that I had discovered an approach that suited me. So in 1979 I had finally found my medium: photography.

Before this I had been working mainly indoors in a studio, with drawing and print-making. With photography I found myself free to go out into the world, to take a car and to be able to go anywhere... that was very important to me.

When I saw American West, one of the gallerists showed me additional work, including prints by Edward Weston and Joel Meyerowitz’s colour prints. Meyerowitz’s C-prints were a real shock to me. The paper was very ordinary, semi-matte, very conventional paper, the kind of paper that was used for amateur snapshots. Although I didn’t shoot in colour for many years, that left a deep impression on me. For me the availability of photographic materials was crucial. It made photography a much more accessible medium than painting or sculpture.

Do you feel that Japan has also shaped you as an artist?

I don’t feel that Japan directly shaped me as an artist. I am just a typical Japanese baby-boomer who grew up in the 1950s. I have a vivid childhood memory of my primary school education being totally focused on American democracy, along with my strong personal longing to discover western culture. Incidentally, there is a Japanese word, 欧米 (oubei), which means western, from Europe or the United States. It seems that we treated these cultures as one and the same.

At the time, we had the feeling that Japanese ‘traditional’ culture, which is my vernacular, was somehow old-fashioned and should have been eliminated along with pre-war militarism. Knowing or learning ‘oubei’ western culture, was new and affirmative. In that era, we got information about western culture mostly through movies or TV. I was one of those that was eager to get to know this ‘oubei’ culture and it became a kind of super- vernacular to me. This desire to understand ‘oubei’ was my first step towards a growing sense that I needed to see the world.

You have said that it is impossible to “suppress yourself as a Japanese” when you photograph. Can you explain what this ‘Japaneseness’ means to your work? How did your exposure to Western photography and art influence your approach?

As a student in my 20s in Europe I was able to see Japan from the outside for the first time: something that I had been interested in for a long time. But when I was in Europe I found taking photographs difficult. Everything was so different and too photogenic. Nothing connected deeply with me. With painting you can break away from this, because you can use your imagination. I wasn’t mature enough as an artist then, so I decided to come back to Japan to make a living and I thought that there I might be better able to take photographs. But when I came back to Tokyo I felt that there was too much chaos. I was trying to find something common, like a highway, something that is the same all over the world. Many times I found that while driving in Belgium I could have been in Japan. I wanted to use this sensation in my work, so I started taking night photographs on highways. Bit by bit, I started working and travelling around Japan.

Before I went to Belgium I had travelled very little in Japan and knew very little about my country. It was travelling around Japan that I finally found my subject: infrastructure. I tried to find something that had never been seen as a photographic subject: the kind of thing that photographers try to eliminate from their images. With painting you can choose what elements to include in a scene, but this is not the case with photography: everything gets included. This distinction between painting and photography was important to me in developing my photographic approach. I felt that technique was not what defined a photographer, but the ability to find a new subject.

Although the infrastructure that you photograph is universal, the landscapes in your images seem very different to what can be seen in Europe. It seems like there is a different relationship to man-made infrastructure in Japan.

With infrastructure such as highways and dams, they are the same all over the world. But perhaps outside of Japan, infrastructure tends to be designed to be hidden. In Japan to build a road, we have to destroy a mountain in the process; the country is 80% mountains. Partly for this reason, in Japan we don’t hide our infrastructure. Instead there is a desire to show people how impressive Japanese engineering is. There is a sense of pride for people to show that their small village has a large dam or an impressive road.

For the Japanese the natural and the man-made are not contradictory. What is important for us is what is necessary. In Japan, we live with constant threat of natural disasters: landslides, earthquakes, typhoons. For us technology is essential to our survival so maybe that changes our relationship to the process of construction in nature. Cohabitation between man and nature is a constant fact of life. So when we build infrastructure it is not hidden. Maybe because Western environmental ideas have been developing in Japan, things are changing, but this idea of necessity remains.

Okutama Town, Tokyo, 2006

With the growth in the importance of climate change and environmental issues in recent years it often seems that we are engaged in a battle between ‘man’ and ‘nature’. People often seem to associate ideas of sustainability and environmental issues with your photographs. How do you feel about this?

Many people often associate environmental issues with my photographs and critics often use these issues as an entry point into my work. However, I try to respect this very subtle balance between man and nature. I think this tension needs to remain for the photographs to retain their power.

When I started taking photographs I was not trying to make a commentary on environmental issues. I was looking for a kind of beauty. For example, compared to a natural waterfall a man-made waterfall seemed more interesting to me. The way in which man tries to replicate a natural process, the choices that he makes to control the flow of water. This was what interested me.

You have now published Landscape 2, your first book of colour work. I’d like to know more about how you shifted from black and white to colour photography?

I have been shooting in colour for many years, since I began working as a photographer really, but I preferred black and white and I chose not to show my colour work. Given the growing difficulty in obtaining black and white materials, this made me consider working more in colour. But in fact colour materials are becoming just as difficult to find, especially the paper. Aside from these very practical considerations, after shooting in black and white for twenty years, I felt it was high time for me to change to take on a new challenge. I have been showing my colour work now for several years and since 2004 I have been concentrating on shooting in colour. For the first two years I shot in both black and white and in colour, but for the last two years I have been shooting almost exclusively in colour. I chose to concentrate on colour since I had decided to do a book of colour work.

You mentioned that it is becoming more and more difficult to get photo materials for film photography. The name of your studio is ‘Darkroom’, this made me think of the disappearance of the darkroom with the rise of digital photography. What are your thoughts on the way that digital technology is changing the photographic process?

To make a good print you have to make a lot of mistakes. In the process you find your taste or preference. With the digital process you can are faced with so many choices, perhaps too many choices. For me I find that my creative impulse gets lost when there is so much choice. It is also a question of habit, I am very used to working with film and it would be hard to break this habit.

Working with a large format camera, there is also a special physical sense that is required. Although digital technology is having a great impact in society, I don’t feel that I need to change my way of working because of that.

Nikko City, Tochigi Prefecture, 2006

How has moving from black and white to colour photography changed the way that you work?

As I said, for the first two years I was shooting both in black and white and colour. Then I realised that everything is different in colour and black and white. With black and white, I just converted colour to tone and gradation. Of course with colour this isn’t necessary: you see things as they are. It took me some time to fully understand this distinction and for a long time I didn’t show my colour work. I didn’t really know the meaning of ‘colour’ in photography. Because I decided to make a book of colour photography, I switched completely to colour and through the process of making the book I realised that there is no special way to see things in colour, you just need to allow yourself to look.

For me colour photography is about atmosphere, whereas with my black and white work I was focused on shape and tonality. In my black and white work by combining those elements of shape and tonality, photography was able to create a different world. I tried to create scenes that people had never seen before. With colour photography the process is more casual, looser. I try to capture an atmosphere.

In terms of the subject matter I go to the same kind of places. Actually the landscapes that I shoot change very rapidly. Within one year a landscape can change completely because of the climate. Japan is a very small country and when you travel to a destination you don’t have many choices about how to get there so I often travel the same roads.

You seem to aim to create photographs that are not rooted in a specific time or place, a specific ‘now’. Your photographs seem often to be outside time in some way.

I take a lot of photographs and show very few. If there is too much reality, too much identifiable sense of time and place, I don’t show these images. I have taken around 4,000 plates with my 8 x 10 camera and of those I only show a few percent. I try to eliminate the reality and any sense of specific time or place. Of course this is extremely difficult with photography. Within a frame there are so many elements that are present and you cannot choose those that you want to keep and those that you want to eliminate. The only elements that you can control are contrast and tonality, light essentially. With painting all the ‘unnecessary’ parts in a scene can be eliminated. With photography, you just have to accept what is there. That is where the difficulty of photography lies. Photography is not something that you can make. It cannot be forced. You have to accept the subject.

Your work must involve long periods of solitary travel. Can you tell me more about how you travel and how much time you spend in places? How important is the experience of travelling in your work?

I travel mostly by car. In winter I head for the South or for places where there is no snow. Snow is difficult to deal with. In the summer I head North as much as possible. I am interested in the direction of the journey but not the destination.

I wander, looking for a subject with a careful mind, respectful of the moment of the encounter. In a way driving is a time of meditation for me. It is a very important part of my process as it brings me the supreme bliss of a chance encounter.

I don’t undertake any research prior to setting out to shoot. This is because I try not to be influenced by a story, episode or the history that a particular place has inherited. I move away quickly after having released my shutter. To try to minimize the affective link that comes from the power of the land, I tend to shoot quickly and to leave the spot as soon as I can.

(Photographs by Toshio Shibata)