Eikoh Hosoe: Master of the Crossroads

Look #0511, May 2011

Since the beginning of a career spanning more than fifty years, Eikoh Hosoe has fashioned a singular photographic vision. By using mythology, metaphor and symbolism, he has created images beyond the limits of traditional photography. His style integrates several different disciplines, drawing upon theatre, dance, film and traditional Japanese art. It is at the crossroads of these various disciplines that Hosoe finds inspiration and the essence of his greatest series.

At the very beginning of his career in the 1950s, documentary realism was de rigueur in Japanese photographic circles. In the post-war years, the ‘objectivity’ of documentary photography provided photographers with an essential means of bearing witness to the effects of the massive destruction of the Pacific War and particularly of the horrors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Like most young photographers at that time, Hosoe started on this path. But he was to change directions quickly and radically, developing an approach that was unique in Japanese photography.

Hosoe became a photographer at a time when the identity of the Japanese nation had been thrown into question following the defeat in the Pacific war, the destruction of the myth of the emperor and the U.S. occupation that ensued. In the face of such turbulent changes, many young photographers of Hosoe’s generation felt the need to develop new photographic approaches to account for the changed world in which they lived. But while his contemporaries sought to renew the documentary genre to present a personal and subjective reality of the real world, Hosoe chose a different direction. He completely abandoned the dominant documentary style to develop an approach infused with a deep sense of experimentation and freedom. Hosoe’s photographic method was characterised not only by its blend of dreams, fantasy and reality, but also by a revolutionary baroque visual style. In a country known for its minimalist, at time austere, aesthetic, this dramatic world sent ripples throughout the Japanese photography scene.

What set Hosoe apart from his contemporaries was his ability to draw on other art forms to create a deeply personal hybrid. Throughout his career, he has drawn inspiration from many artistic disciplines, but it is dance—and particularly Butoh—that has been at the heart of his greatest series of photographs. Thanks to the celebrated writer Yukio Mishima, Hosoe met Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the founders of Butoh dance. This revolutionary movement founded in the post-war years, incorporated elements of German Expressionism and Japanese dance in the search for a new social identity. Dazzled by Hijikata’s performance of Kinjiki (Forbidden Colours), an adaptation of the novel by Yukio Mishima, in a small Tokyo theatre, Hosoe began photographing this unique dancer, a collaboration that continued until Hijikata’s death in 1986. This association with Hijikata led to many of Hosoe’s photographic series, and this unique artist has remained deeply influential to this day.

It was with Man and Woman (1959) that Hosoe burst onto the photographic scene in Tokyo. Using dancers as his models, Hosoe produced a series of starkly contrasted images sequenced as a performance which was a new interpretation of the union between two bodies. After the success of Man and Woman in 1961 Hosoe travelled to the coast to continue his work on the human body in a series he entitled Embrace. But after the sudden shock of discovering Bill Brandt’s book, Perspective of Nudes in a bookstore in Tokyo, Hosoe decided to abandon the series and was not to resume it until ten years later.

The influence of Tatsumi Hijikata once again played a role in Hosoe’s next project. It was through their shared admiration for Hijikata, that Hosoe came to know the writer Yukio Mishima, one of the greatest Japanese writers of the twentieth century and a highly controversial figure. In 1961, Mishima saw photographs of Hijikata by Hosoe and invited the photographer to work with him, a collaboration that led to Barakei (Ordeal by Roses), published in book form for the first time in 1963. With Barakei, Eikoh Hosoe’s ‘photographic theatre’ first opened its doors. Inspired by the theatricality of the writer’s house, Hosoe was given free reign by Mishima to create an extraordinary baroque, erotic and at times morbid performance for his camera. A few years later, Hosoe and Mishima decide to publish a second edition of the book, the publication of which Mishima timed to coincide with his suicide by seppuku, giving a more sinister undertone to these images.

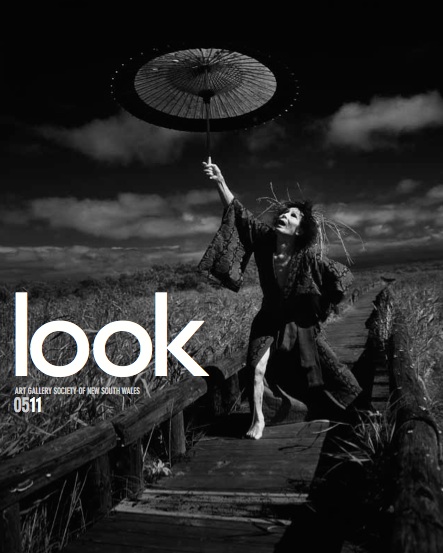

The theatricality and drama of Barakei can be found in a different form in a further collaboration between Hosoe and Hijikata. For the series Kamaitachi (1965-1969), Hijikata embodied a mythical demon that was said to haunt the rice fields of the rural region of Tohoku in northern Japan, to which Hosoe had been evacuated during the war. The series was a dramatization of the photographer’s childhood memories in which Hijikata vividly embodied the kamaitachi demon. It is perhaps the best illustration of Hosoe's style, combining performance and documentary with a dramatic and baroque aesthetic that embodies the principles of ankoku butoh (dance of darkness).

Hosoe’s relationship with Butoh extended to another of the movement’s most celebrated performers, Kazuo Ohno. Through his relationship with Hijikata, Hosoe began to photograph Ohno, culminating in a collection, The Butterfly Dream, which spans across the dancer’s entire career. Hosoe named his photographic exploration of Ohno’s unique art after the famous Daoist analogy in which the philosopher Zhuangzi dreamt that he was a butterfly, but once he had awoken, wondered if he was a man dreaming of being a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming to be Zhuangzi. For Hosoe, this analogy was the perfect encapsulation of Ohno’s freedom as a performer. Together with Kamaitachi, Butterfly Dream provides a fascinating insight into the evolution of Butoh, while illustrating Hosoe’s ability to develop unique visual universes from these performers’ contrasting styles. While they retain the drama intrinsic to Butoh, Hosoe’s photographs of Ohno are far less explosive than those of Hijikata, often focusing in on details of Ohno’s body, the curve of a wrist or a facial expression caught between agony and ecstasy.

From the beginning of his career, Hosoe established himself as a master of black and white, preferring it to colour as it allows him to “photograph the essence of his subject.” However, more recently, Hosoe turned to colour for the series Ukiyo-e Projections, a tribute to Tatsumi Hijikata and the experimental Asbestos Dance Studio founded by Hijikata and his wife. Inspired by his notion that Butoh is a modern form of Ukiyo-e, for Ukiyo-e Projections he projected onto the bodies of a Butoh dance troupe a combination of his own black and white photographs with shunga images by noted Ukiyo-e artists such as Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai and Suzuki Harunobu. This series was born when Hosoe found out that the Studio was to close in 2003 after forty years of activity. Upon hearing about the closure, Hosoe felt the need to pay a photographic tribute “to express gratitude for all that it had produced.” Ukiyo-e Projections was completed on stage at the Studio during a series of sessions in 2002 and 2003.

The exhibition, Eikoh Hosoe: Theatre of Memory highlights Hosoe’s extraordinarily productive relationship with the world of Butoh, while also revealing his mastery of and experimentation with photographic printing techniques. Throughout his career Hosoe, a master printer, has experimented with both film-based and digital techniques to develop new methods of photographic expression. In recent years, he has combined new printing technologies with Japanese washi paper to present his work on traditionally made silk screens and scrolls. Working with a printer, he produced prints on washi paper which he dubbed somezuri (dye-print) as this type of paper is very absorbent, allowing the ink to penetrate it deeply rather than remaining on its surface. With the assistance of Kyoto craftsmen, he began presenting his work in the form of byobu (screens) and kakejiku (scroll painting). These ‘photo-scrolls’ recall the spirit of photogravure used in the golden age of photo-book publishing in Japan in the 1960s, while also drawing upon centuries of Japanese artistic traditions. They provide a fascinating new reading of Hosoe’s work, occupying a new space between the photobook and the print and highlighting his continued commitment to pushing the boundaries of photographic expression.

By Marc Feustel