Too Few Stories?

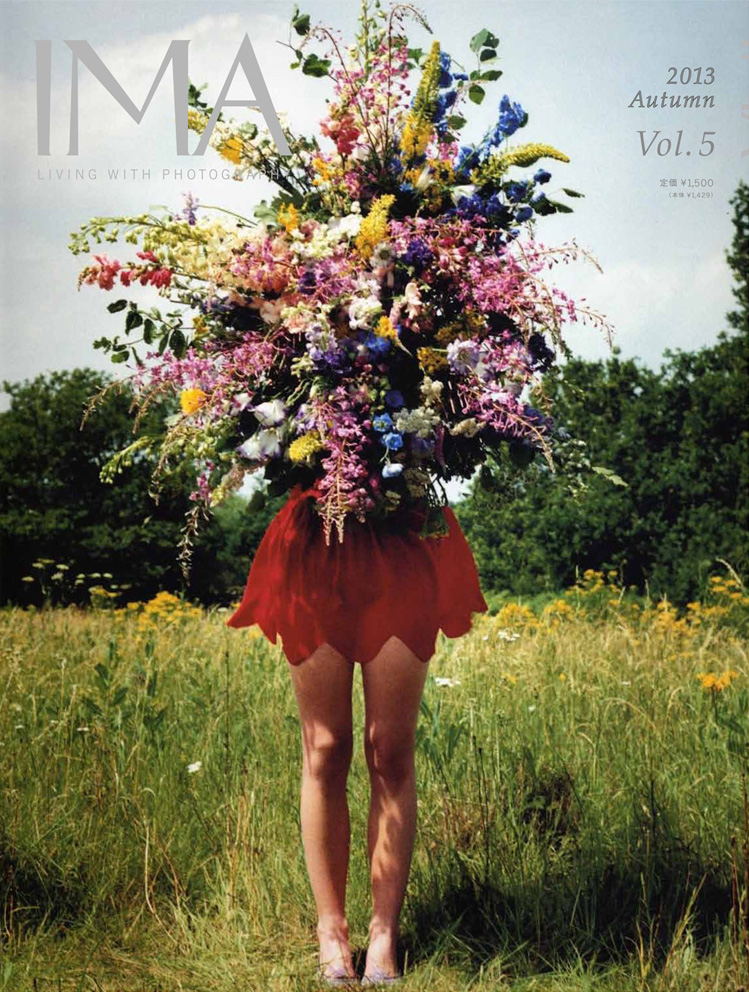

IMA, Vol. 5, Autumn 2013

For several years now, the photography world has been going through a photobook boom. Considered to be mere by-products of photographic work for many years, suddenly photobooks have been given pride of place. At the end of last year, I spoke with Cristina de Middel, whose self-published book The Afronauts was one of the most talked about books of 2012, about this boom and she made the interesting point that fewer and fewer photobooks rely on narrative. In recent years photography has become more closely aligned with the world of contemporary art, rather than with other narrative-based media like film. As a result, photography has become increasingly driven by conceptual ideas and formal considerations rather than by stories.

Yukichi Watabe, A Criminal Investigation

Although many contemporary books have been less story-driven, one of the best examples of the use of narrative in a photobook is a recent one: Yukichi Watabe’s A Criminal Investigation, first published in 2011 (a new book of this work is being published this September in Japan by Roshin Books). The book focuses on a particularly gruesome murder committed in the late 1950s when a dismembered and disfigured body was discovered near Sembako Lake northeast of Tokyo. A special unit was set up to investigate the crime and Watabe, a freelance photojournalist at the time, managed to gain special access to the investigation. While the book reads very much like a classic crime story, it does not tie up neatly like most crime dramas. In fact the unit was unable to solve the crime, and it was only by chance that the murderer was apprehended several years later. Although this book is based on true events, the publishers had little other information apart from the images themselves and so they constructed a story of their own, a fictional narrative built from a series of journalistic images. They chose to maintain the open-endedness of the story by building a narrative full of twists, turns and dead-ends, that never reaches a resolution.

Cristina de Middel, The Afronauts

In the case of de Middel, her book The Afronauts also revisits a historical episode, but in an altogether different and more playful way. In 1964, after gaining independence, Zambia started a space programme led by schoolteacher Edward Makuka Nkoloso, the National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy, who dreamed of sending the first African astronaut to the moon. He failed to secure any government funding and, as a letter explains in the book, the programme “died a natural death”, becoming no more than an amusing historical footnote. However, nearly fifty years later, de Middel used it as a premise for her first book project, creating a kind of posthumous photo-album from her own photographs, manipulated documents, drawings and letters. Interestingly de Middel describes the book as being “like a short, small and very modest movie production.” Unlike A Criminal Investigation, The Afronauts does not bear any of the hallmarks of a ‘true story’: it wears its fictional nature on its sleeve and instead is an almost fantastical tale of what that programme might have been that plays with clichés of Africa and of space travel.

Lieko Shiga, Rasen Kaigan

Stories in photobooks do not always take the form of a traditional linear narrative with a defined beginning, middle and end. In the case of Hiroh Kikai’s portraits taken in Asakusa, he uses short, carefully crafted captions that suggest a back story to each of the people he has photographed, adding many potential layers to each of his images. One of the most talked about projects of the past year, Rasen Kaigan (Akaaka, 2013) tells an extraordinarily complex story of the small community of Kitakama in Sendai prefecture. The book shifts between the personal narratives of the villagers, the wider narrative of the community and the impact of 3/11. The narrative of the book functions like a complex web, with individual stories linking and overlapping to create a labyrinthine whole that is intentionally difficult to decipher, but no less powerful for it.

The American photographer, photobook collector and book-maker John Gossage recently made the following comment on a Facebook group devoted to photobooks, “I suspect that ‘Too much book craft, too few good pictures’ is what people will think about the current moment.” Perhaps it is also true that today, too few photobooks have good stories to tell.

By Marc Feustel