Vitas Luckus: A Photographer Possessed

IMA, Vol. 18, Winter 2016

An essay on the work of the Lithuanian photographer Vitas Luckus, a key figure and relentless troublemaker in Soviet photography from the 1960s to the 1980s.

There is a photograph of Vitas Luckus with his grandmother, a self-portrait taken in a mirror, which perfectly encapsulates the Lithuanian photographer’s approach. Their faces both wear the beginning of a smile, and they appear to be looking into each other’s eyes. One of his hands is wrapped in a bandage, a sign of his tendency to get himself into trouble. Above all, this image illustrates Luckus’s rare ability to connect with those that he photographs. His frantic and gleeful energy often spills over into his images and although he spent most of his time behind the camera, his presence is always keenly felt.

Born in 1943 in Kaunas, Luckus became a key figure in Soviet photography, despite his tragically short-lived career. After graduating with a degree in drawing and painting, he joined the photography club in his native city and eventually became the club president. From the 1960s to the mid-1980s, Luckus travelled across the Soviet bloc, photographing people from all walks of life, from peasants to performers. Over this period he assembled a remarkable body of work which is a mix of street photography and portraiture, documentary and performance.

The portrait was probably Luckus’s favourite photographic tool and his use of it was anything but conventional. He was not afraid of getting close to his subjects, their faces often filling the frame entirely. This dynamic style is characteristic of his approach, one which pushed the boundaries of the photographic aesthetics of the time.

His images of both rural and urban life provide a sweeping view of the Soviet Union, from his hometown of Kaunas to the Altai Krai or the Republic of Bashkortostan. But the photographs Luckus made on these travels are far from mere documents. Instead, they feel more like the fruits of the photographer’s interaction with these people and places. In the 1994 book The Hard Way (Edition Stemmle), the journalist Herman Hoeneveld writes, “[Luckus] had a unique inspiring and stimulating effect on others,” a quality that is evident in his images

Luckus’s work bears none of the sombre hallmarks associated with Soviet era photography, instead it exudes a sense of playful exuberance and mischief that brings to mind the work of Jacques-Henri Lartigue, although Luckus inhabited a very different world to the Frenchman. Luckus referred to himself as dvarniazka, the Russian term for mutt, and his photographs are full of energy, taken by someone who appears to be in constant motion. “He photographed both for God and for the devil, and worked as if possessed,” writes Hoeneveld, working “for days on end with a minimum of sleep and alcohol.”

In addition to his heavy drinking, Luckus also had a penchant for confrontation. His work was censored on several occasions and he had frequently been followed by government informants and police. In March 1987, a KGB agent came to his home to question him. Luckus was angered by the interrogation and the exchange escalated into a fight during which the photographer stabbed and killed the man. Moments after the incident, his wife Tanya found Luckus in the snow: he had jumped to his death from the balcony of their apartment.

His widow, who was both his muse and a frequent contributor to his work, maintains his archive today, having moved to the United States in 1991 and since remarried. Until recently, his work had been all but forgotten, but thanks to Tanya Luckus (now Aldag) his work has been brought back into the spotlight.

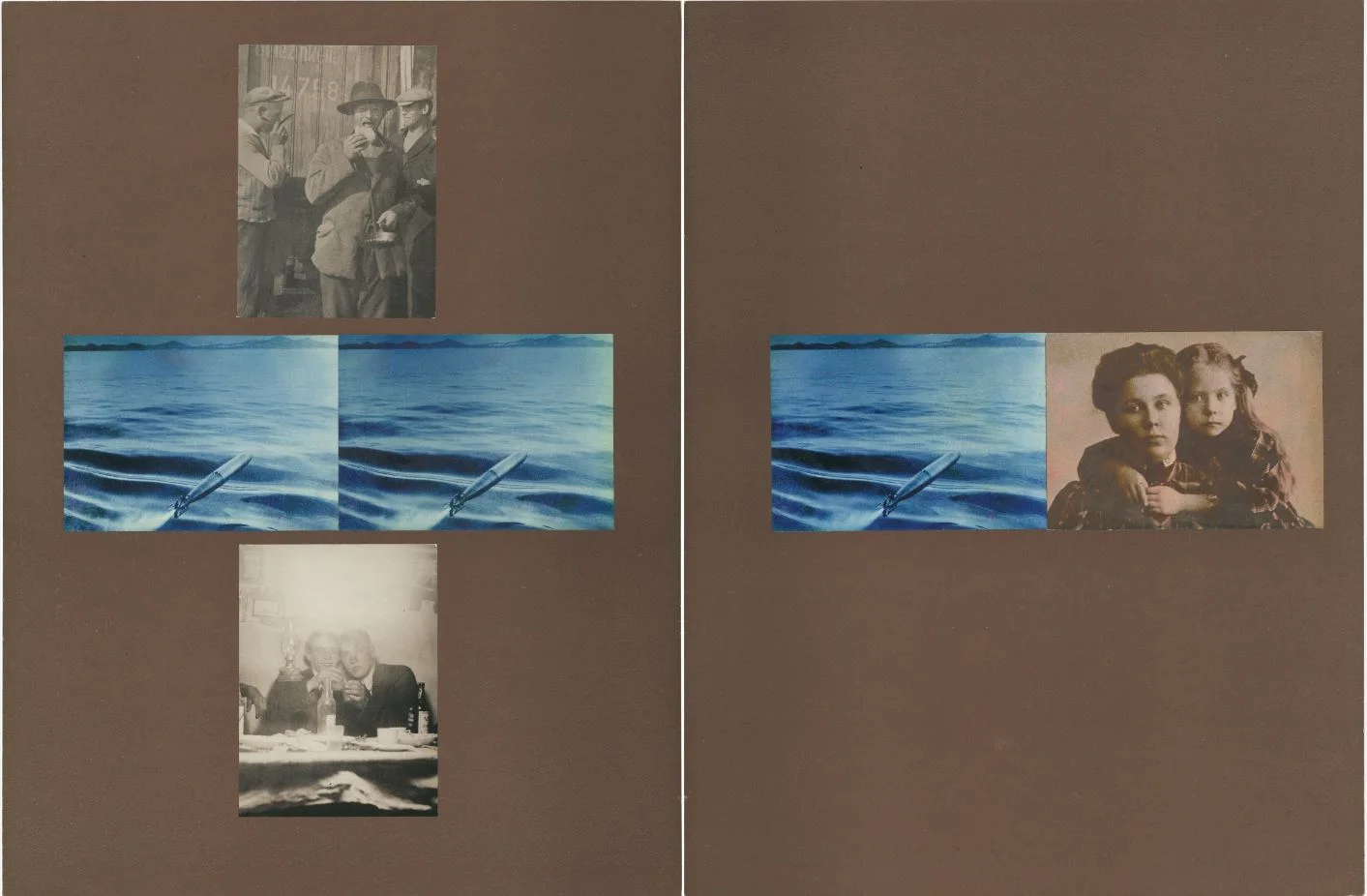

In 2013 an exhibition of the series Improvising Pantomime (1971-73) was held at the Lithuanian embassy in Washington D.C. This series which makes use of ornate mounts, layered images and a heavy dose of vivid, psychedelic colour shows Luckus’s keen eye for design and inventive spirit. Those qualities also come to the fore in his final project, A Take on Vintage Photography, an extensive montage from a large collection of photographs. Luckus made the series into a book, deliberately excluding text and titles and making intelligent and subversive use of crops, close-ups, layered and repeating images to create a remarkable and highly personal visual compendium of the world.

Writing about the project in his diary, Luckus says: “In the beginning I tried to classify my work according to social phenomena and photographical style, emphasizing the topic of life and death. This made me feel like a Lithuanian artist carving statues of God or the saints. When I put everything on the table, however, I felt like a god myself. In front of me I had an Asian and a Red Indian, a Negro, a white, a Moslem, a Buddhist, a Christian, the Czarist army, the Polish army, the Kaiser, the war, funerals and weddings. I shuffled thousands of images into a heap and found they were an orderly heap of life, because everything here was life and because all of us, whether a boxer, a Czar, a beggar or a half-naked woman were disclosed here. Archive photography seemed to me to reflect a bottomless well, waiting for someone to look into it and understand it.” Luckus’s prescient sense of the importance of the archive makes this a series that wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary photography exhibition.

When Vitas Luckus Works (Kaunas photography gallery, Lithuanian art museum, 2014) won the Historical Book Award at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2015, many must have wondered why they had never heard of this artist before. Thanks to his widow’s efforts, Luckus’s work is finally coming back into the light.

by Marc Feustel