The Age of the Selfie

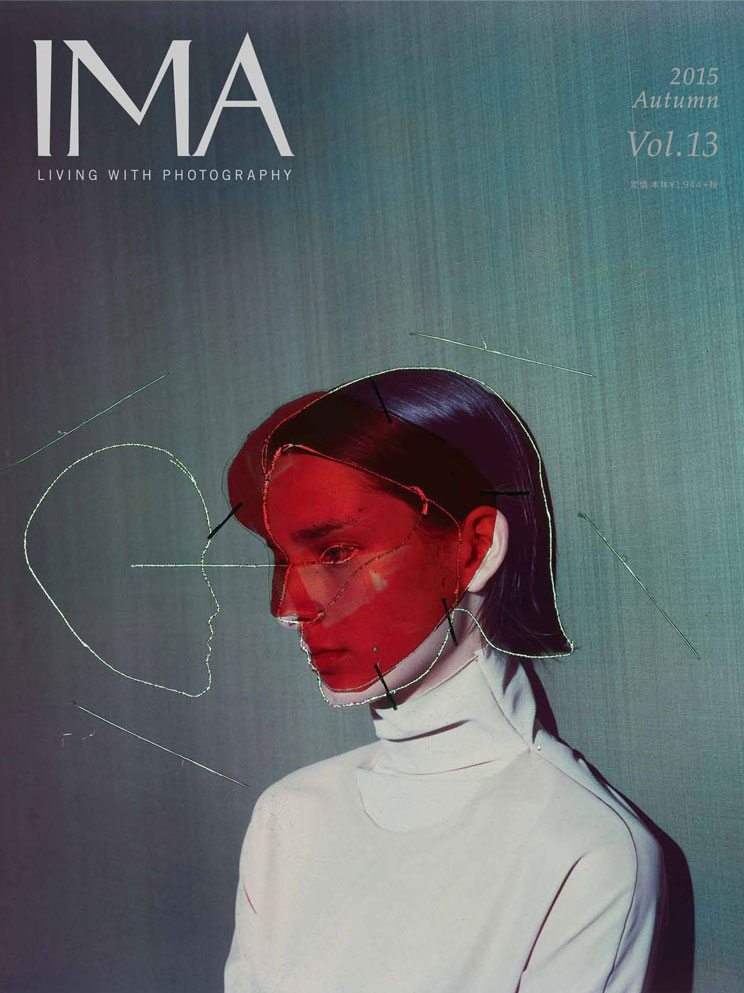

IMA, Vol. 13, Autumn 2015

Selfie: a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.

In November 2013, the Oxford English Dictionary selected the word “selfie” as their word of the year after the frequency of the term in the English language increased by 17,000% in the space of a single year. The selfie is now the most ubiquitous genre of photograph of them all, giving rise to the selfie stick (now a global multi-million dollar business) and a host of sub-genres, from the infamous “duckface” pout to the “artselfie”—the recent trend of taking selfies with works of art. In the Philippines, one of the world’s most selfie-obsessed nations, a museum devoted entirely to the artselfie has opened in Manila where 3D replicas of famous works of art act only as backdrops for the visitors’ smartphone self-portraits.

Although the selfie has become a global phenomenon, until recently it was considered to be little more than a passing trend, too disposable to be relevant to the world of art photography. However, the selfie has begun to get attention from some surprising circles. In fact it has begun to be taken rather seriously, becoming the subject of art projects, thematic exhibitions, and essays by leading art critics.

British photographer Martin Parr, a champion of the everyday absurd, recently posted a series of images of people taking group selfies on his blog. For Parr the selfie stick trend is welcome “as, interestingly, you can get the whole scene in front of the camera and the backdrop all in one photo.” Beyond such documentations of the selfie craze—and the strange public behavior that it can lead to—a growing number of contemporary artists are creating work that engages more deeply with this trend.

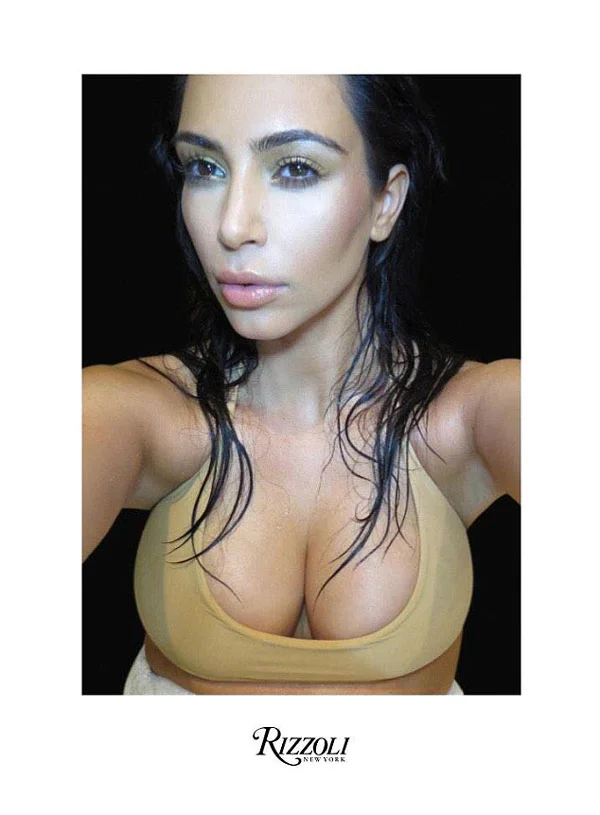

One of the most talked about—and controversial—exhibitions of 2014, Richard Prince’s New Portraits, involved the appropriation of portraits and selfies from a number of Instagram accounts. Prince’s project drags the ephemeral, disposable world of social media imagery into one of the temples of the contemporary art world—Larry Gagosian’s New York gallery. However, the crowning glory of the selfie movement thus far has to be Selfish, a book published in May 2015 by the queen of the selfie herself, Kim Kardashian.

Kim Kardashian, Selfish

Kardashian, who has allegedly been taking selfies over the course of three decades (far before the term was first coined in 2002), compiled no less than 445 pages of them in Selfish. With a signed special edition of 600 copies followed by a trade edition, Selfish borrowed the codes of the art book and seemed to position itself as an object to be treated with seriousness. In fact, one of America’s leading art critics, Jerry Saltz, has written about in glowing terms, describing it as “a kind of American My Struggle—Karl Ove Knausgaard’s epic…. A chorus of one, written in a personal language of compassion, infinite theater, stage sets, set pieces, ceremony, shallowness, despairs, self-awareness, sexuality, unable to curtail one's selfishness and obsession with one’s own image.”

The rise of the selfie is hardly surprising given that it has become so fundamental to the language of social media. It is the natural visual response to social networks’ invitation (or indeed demand) for us to constantly display ourselves through the food we eat, the oceans we swim in, the museums we visit, and the endless fun we are in the process of having.

This contemporary obsession with constant self-representation has led to a series of self-portraiture projects that borrow the language of the selfie or investigate its dynamics in myriad different ways. For her project Daily Exhaustion, the prolific Dutch artist Anouk Kruithof used the selfie to explore an emotion that it rarely depicts: the state of complete exhaustion. Korean Jun Ahn’s selfies are taken on the edge of cliffs, skyscrapers and stairwells, creating an unusual perspective and an altogether different, unsettling relationship to the landscape while Thomas Mailaender takes the thrill-seeking selfie even further with a tongue-in-cheek take on extreme tourism.

David Horvitz, Public Access (Pismo Beach), 2011-2014

While David Horvitz’s Public Access doesn’t contain any selfies as such, by transforming landscape photographs into self-portraits, it questions the way in which images are categorized and circulate online. Over the course of two weeks, Horvitz took a series of pictures of himself looking out over the California coastline, which he then uploaded to the Wikipedia entries for each location, creating a flurry of activity on the network as users questioned the provenance of these images, and eventually cropped or deleted many of them.

Others have developed a practice of the self-portrait that feeds as much on contemporary media and pop culture as it does art history. The photographer and performance artist Jaimie Warren blends high and low art with her series of photographic tableaux, Art History, mixing Hellraiser with Dürer or Fra Angelico with Michael Jackson and Missy Elliot. In Project Diaspora, which Omar Victor Dirop describes as a “visual pilgrimage through art history,” the Senegalese artist subverts original paintings of notable African men in European history while using football equipment as props—a much needed reintroduction of the African image into Western art history.

The proliferation of different approaches to the self-portrait presented here belongs to a grand tradition stretching back to the first known photographic “selfie” taken by Robert Cornelius in Philadelphia in 1839. Over time the self-portrait has proved to be a powerful artistic tool to engage with questions of personal and collective identity and representation. In an age where self-image has become everything, it has surely never been so relevant.

By Marc Feustel