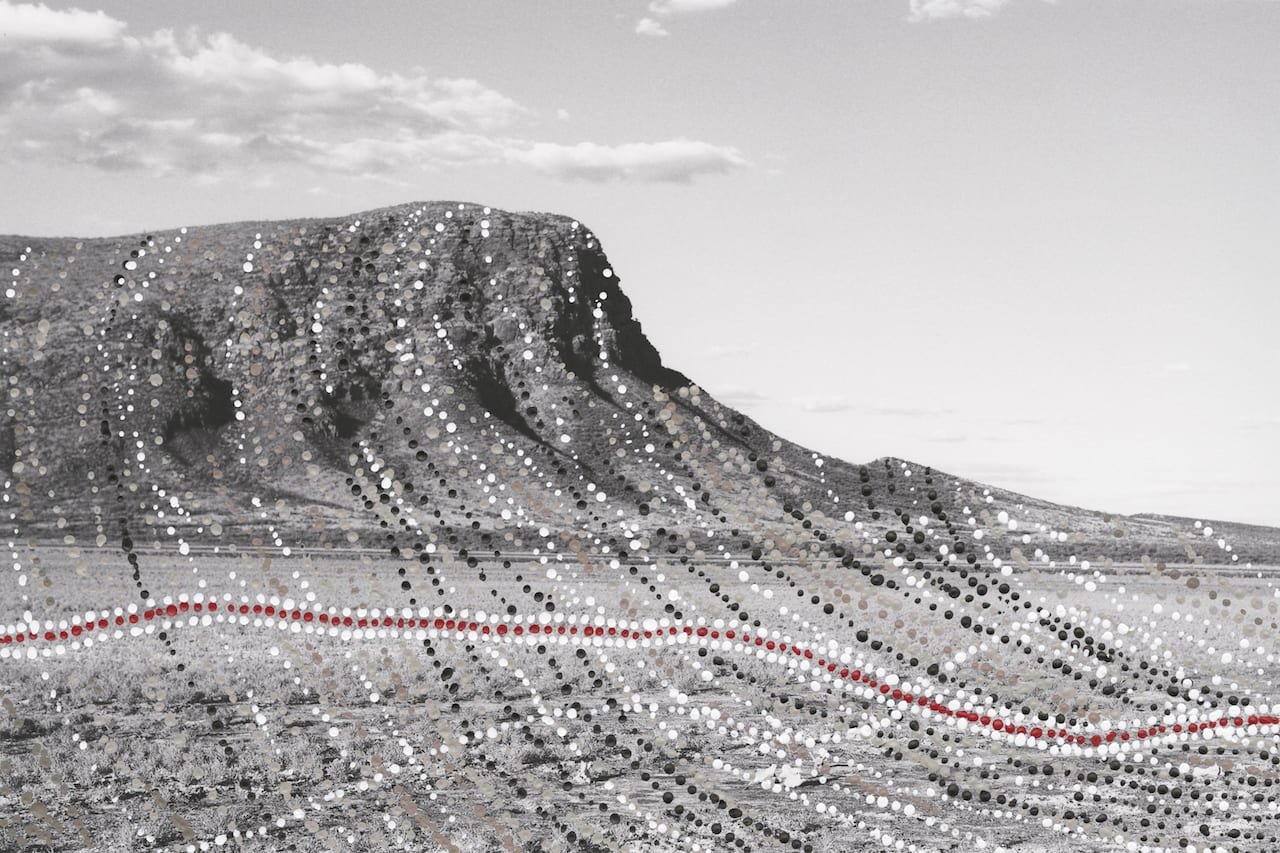

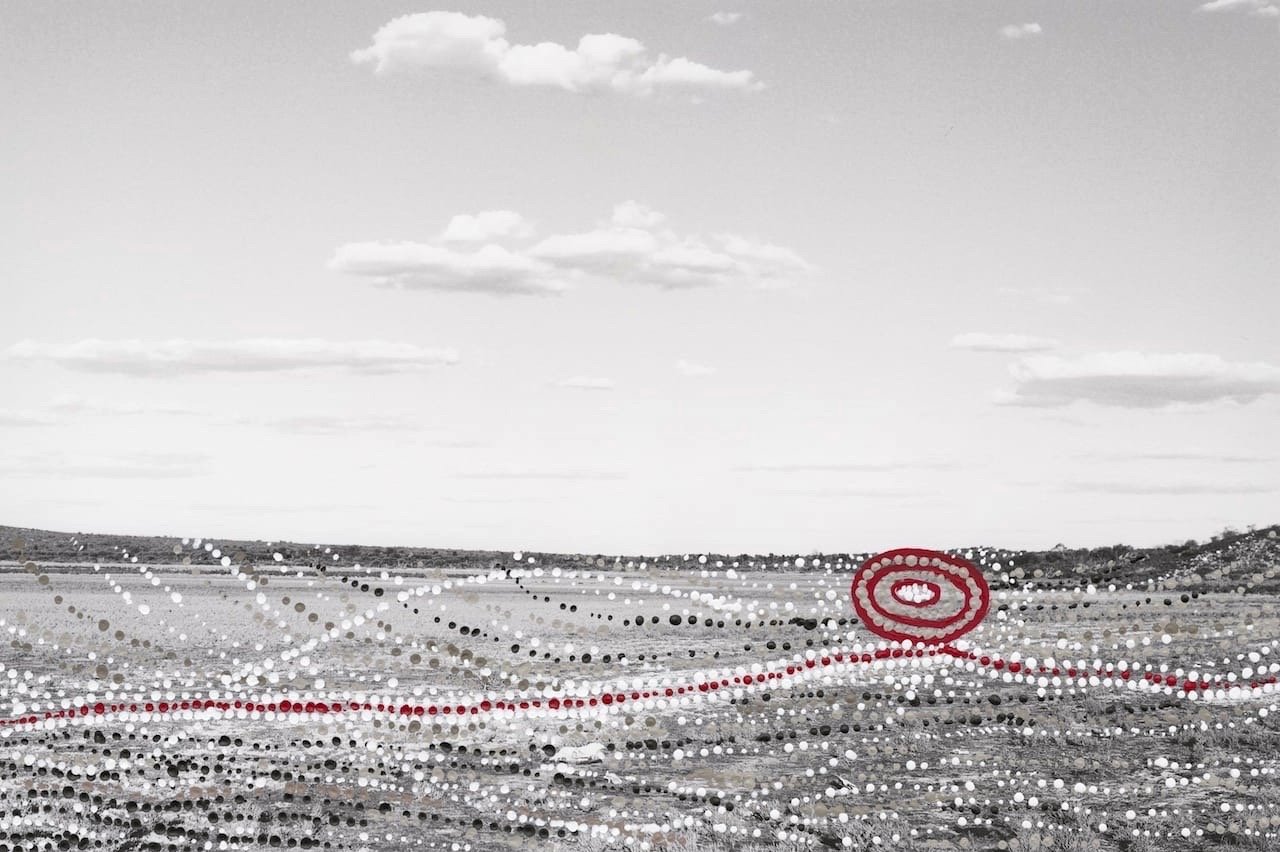

Patrick Waterhouse, Restricted Images. Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia

Joji Hashiguchi, We Have No Place to Be. 1980–1982.

Foam Magazine, N°56, Spring 2020

Patrick Waterhouse, "Restricted Images. Made the Warlpiri of Central Australia”

For issue no. 56 of Foam magazine, I wrote about Patrick Waterhouse’s collaborative work with the Warlpiri of Central Australia. Here is an extract :

In 1899, the ethnologists F. J. Gillen and Baldwin Spencer published The Native Tribes of Central Australia, the first major anthropological study of Aboriginal culture. This publication brought the Aboriginal community to the attention of a European audience and was also notable for its ground breaking fieldwork and use of photography.

Gillen and Spencer’s work was done at a time when the prevailing view of Aboriginal people was one of total contempt: in 1884, Thomas McIlraith, the former Prime Minister of Queensland described Aboriginals as ‘miserable wretches’ whose ‘savagery is ineradicable’. The Native Tribes of Central Australia instead revealed a highly sophisticated culture with complex systems of customs and beliefs. In effect, the authors were the progressives of their time but their work was heavily tainted by the language they used and their proposals for the treatment of Aboriginal people — they advocated for the separation of Aboriginal children of mixed descent from the rest of the Aboriginal population — which would be unconscionable today.

Grandparents Used to Walk This Way. Restricted with Alma Nungarrayi Granites, 2014 - 2018.

This deeply problematic legacy is at the root of British artist Patrick Waterhouse’s long-term project on—and with, but more on this later—Australia’s Aboriginal peoples. In 2011, Waterhouse made his first trip to the Australian outback during which he encountered Aboriginal communities and became interested in how they had been historically represented.

Using Gillen and Spencer’s book as a starting point, Waterhouse began to gather archival materials from museums and private collections in Australia and Europe to assemble a composite picture of the ‘competing historical narratives of Australia’ and the representation of its Aboriginal cultures from the colonial standpoint.

Waterhouse then brought this archive to one of the longest-standing Aboriginal-owned art centres in Central Australia, Warlukurlangu Artists in Warlpiri country, in order to start a conversation around this problematic history of representation. This conversation evolved into a collaboration in which Waterhouse invited the artists of Warlukurlangu to paint over a number of the documents in the archive using the Aboriginal dot painting technique, resulting in the series Revisions. While this may appear to be a purely aesthetic device, particularly as the technique tends to use vivid colours and eye-catching patterns, it was in fact developed specifically for the purpose of obscuring information from the viewer.

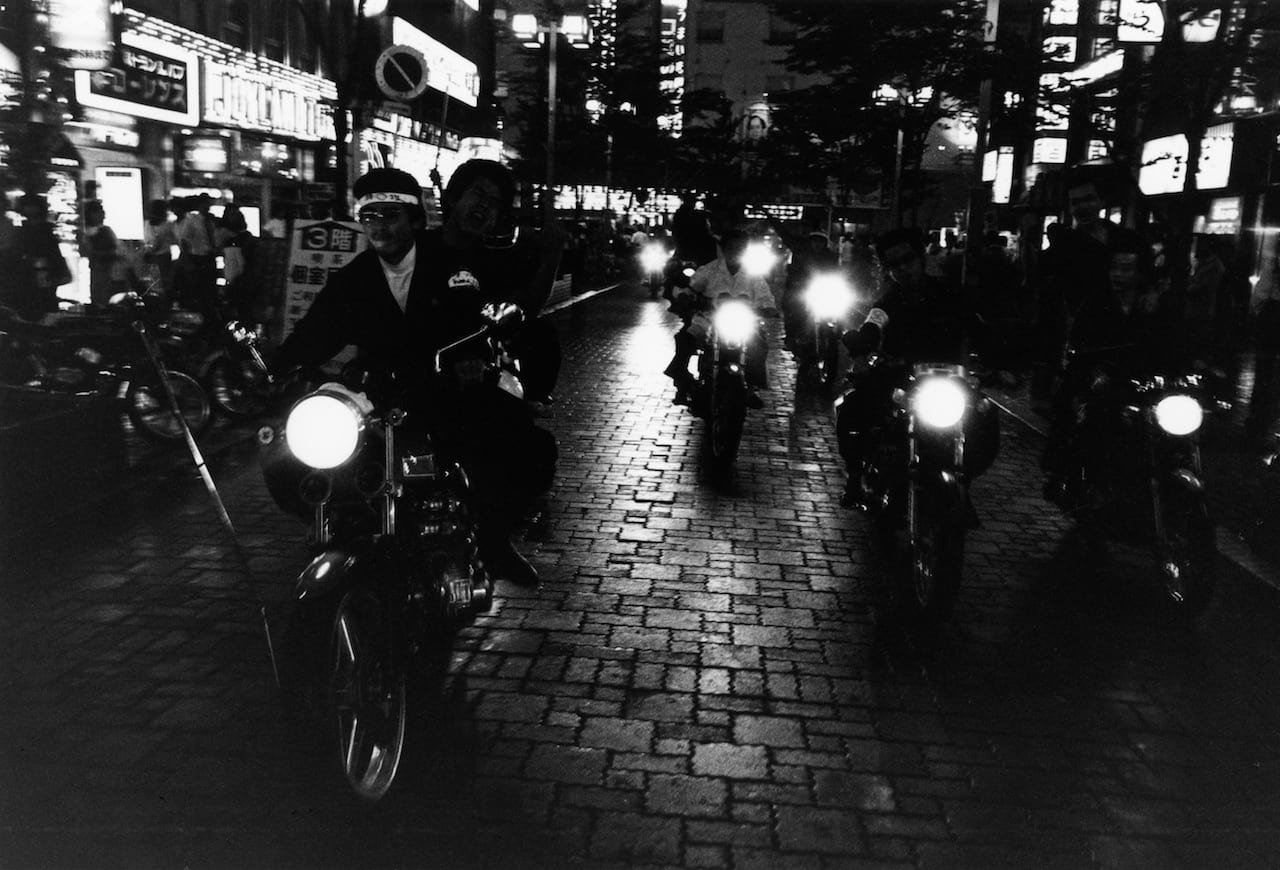

Joji Hashiguchi, “We Have No Place to Be. 1980–1982”

For the Elsewhere issue, I also wrote about Joji Hashiguchi’s work from the early 1980s on youth counter-cultural movements in cities around the world. Here is an extract:

In his first photographic project, Joji (also known as George) Hashiguchi, focused on Tokyo’s outsider subcultures, from the gangs of rockabilly street dancers known as the takenoko-zoku who hung around the Harajuku district, to the cornucopia of Shinjuku’s ‘human zoo’. Shisen (The Look, 1981), earned Hashiguchi the Taiyo Prize and led him to expand his exploration of youth culture beyond Japan.

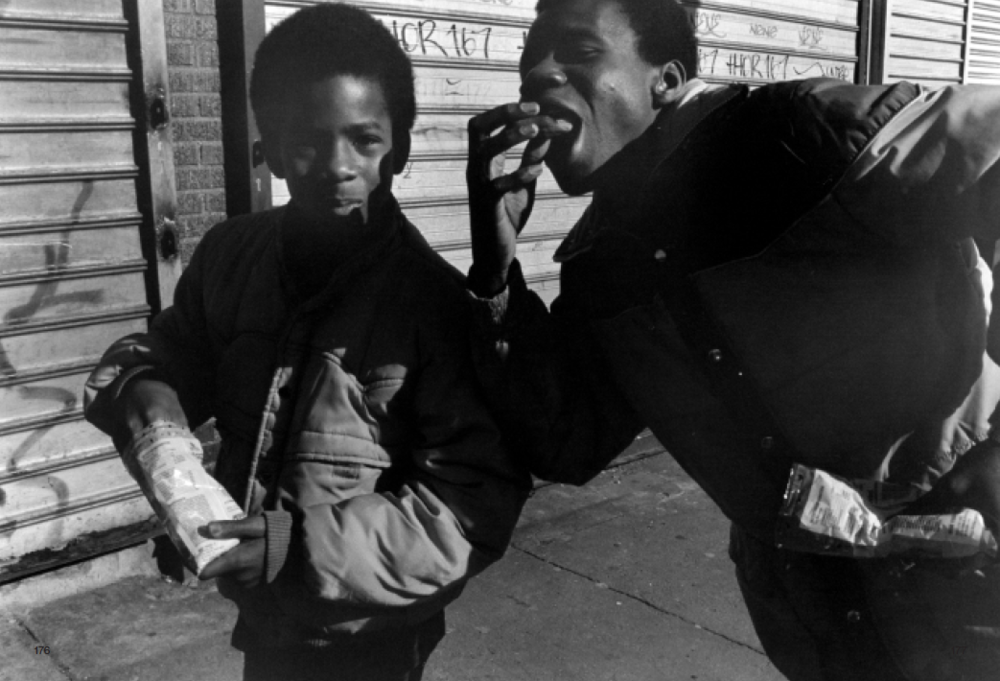

In the summer of 1981, having read about some of the protest movements taking place in Europe at the time, Hashiguchi left Japan for a three-month journey to Liverpool, London, Nuremberg, West Berlin, and New York. Hashiguchi’s itinerary was driven by his interest in the conditions faced by young people in these cities and their efforts to find their place within them. He was drawn to outsiders and minority groups—London’s skins, heroin addicts in East Berlin, black teenagers in New York — those that reflected the systemic issues these cities faced.

The photographs he took during these travels became Hashiguchi’s first book, Oretachi Doko ni mo Irarenai: Areru Sekai no Judai (We Have No Place to Be, Soushisha, 1982). Combined with his debut series Shisen and a number of previously unpublished photographs taken during this period, they now appear, some four decades later, in the latest book by New York based Session Press, We Have No Place to Be.