Daisuke Yokota, Taratine

(New York: Session Press, 2015)

I wrote the afterword for Daisuke Yokota's book Taratine, the most personal of his publications so far, which is based around the taratine gingko tree found in Japan's Aoyama prefecture.

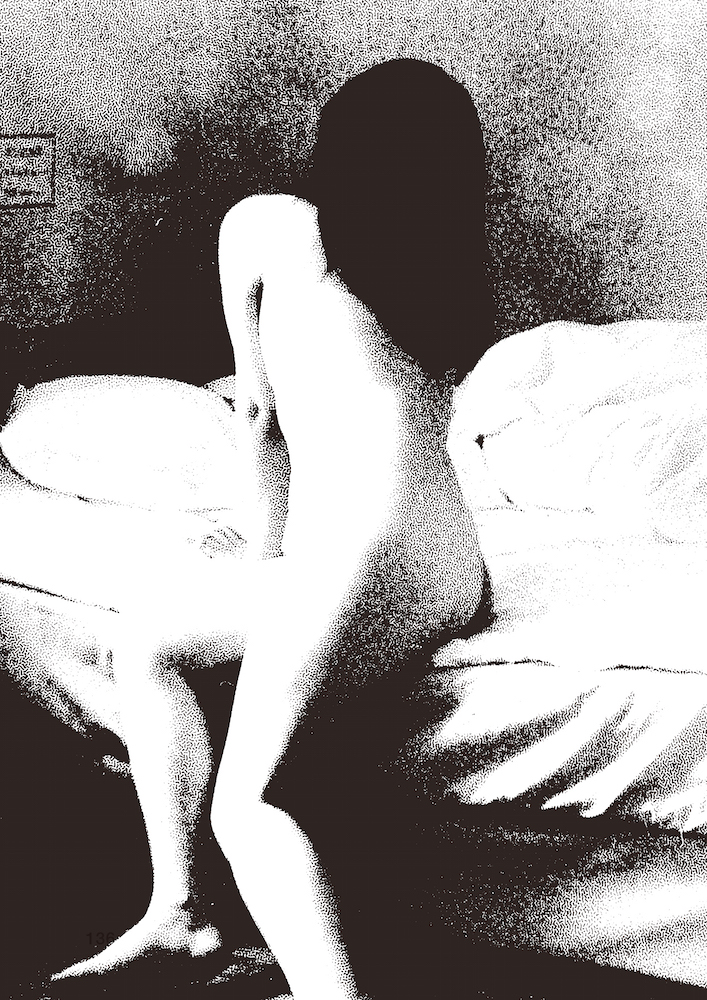

The first thing you notice about Daisuke Yokota’s photographs is their texture. It might be the coarse grain of the film or the dust and hairs strewn across its surface. The emulsion itself often appears to have been pushed to breaking point: cracks, blisters, and burns proliferate creating a surprising sense of depth and tactility.

Yokota pulls his creations apart, exposing layer after layer of their composite parts, and drawing our attention to the fact that we are looking at a photograph and not an image. His interventions are akin to a photographic open-heart surgery, revealing the complexity and fragility of a photograph by deconstructing its anatomy.

One cannot help but make the link with the now legendary generation of photographers who came of age in late 1960s Japan. The gritty materiality of his work resonates with that of past masters such as Daido Moriyama or Takuma Nakahira. But beyond an undeniable aesthetic kinship, what brings Yokota closest to these pioneers are his tireless attempts to create a new photographic language.

Nakahira and Moriyama shook photography to its foundations, tearing down its existing structures and frameworks in order to develop a new, radical photographic vocabulary which captured and reflected the turbulence of the world surrounding them. Yokota has taken his photographic explorations in an altogether different direction. His work is driven not by the social and the political but by the personal and the emotional. His photographs are evidence of a profound sensitivity and an ability to translate both emotion and sensation in an unusually potent way.

This body of work takes its name from a particular gingko tree, which Yokota encountered while travelling through Japan’s northern Aoyama prefecture in 2007. Known as taratine (垂乳根), the tree is believed to be more than one thousand years old. Its Japanese name can be translated literally as “drooping breast roots” and it has been worshipped by many generations of women for its ability to enhance fertility.

Taratine is Yokota’s ode to the women in his life and perhaps even to love itself. It brings together a group of recent photographs of intimate spaces and moments with a more expansive body of images shot during that journey north eight years earlier. As Yokota’s most profoundly personal and indeed nostalgic project, it represents a significant departure from his previous work, following in the Japanese tradition of the photographic I-novel, from Araki’s Sentimental Journey (1971) and Yoko My Love (1978) to Masahisa Fukase’s Yohko (1978) and Karasu (1986) among many others.

However, unlike its predecessors, Taratine is driven by a more ambiguous and slippery set of emotions and sensations. A need for maternal love evolves into lust and desire. The sensations of sticky humidity on a boyhood summer’s day resurface decades later in a hotel bedroom. Taratine is as much a book of sounds and smells as one of images—a heightening of all our senses that breathes fresh air into a grand Japanese tradition.

By Marc Feustel